This feels deeply inappropriate, I thought, as I started watching Erika Kirk’s hagiographic eulogy. I am watching a grieving widow in order to analyse her performance, and pass judgement on her message. Her husband was brutally murdered just ten days ago – let her grieve. Don’t use her as journalistic material.

But anyone who chooses to speak of the most serious matters, in whatever circumstances, is subject to criticism. Being a victim of some terrible act of violence is no exemption. Victim status does not authorise one to tell a nation what the essence of Christianity is, for example, and expect one’s account to be unchallenged.

Her forgiveness of her husband’s killer was certainly impressive

When she walked on stage at the memorial in Arizona, I was wondering how this young woman would cope with the situation: a huge packed stadium, greeting her with extreme enthusiasm, with whoops of adulation, like she was an icon, a new embodiment of their shared purpose. Huge sparklers showered the stage, as if this were a Taylor Swift concert. How would she deal with the immense strangeness of it all, I wondered. She seemed overwhelmed, as she first took it all in. But I needn’t have worried. She quickly showed that she was an amazingly confident performer. Soon, she even seemed at ease, despite everything, as if she was born for this role.

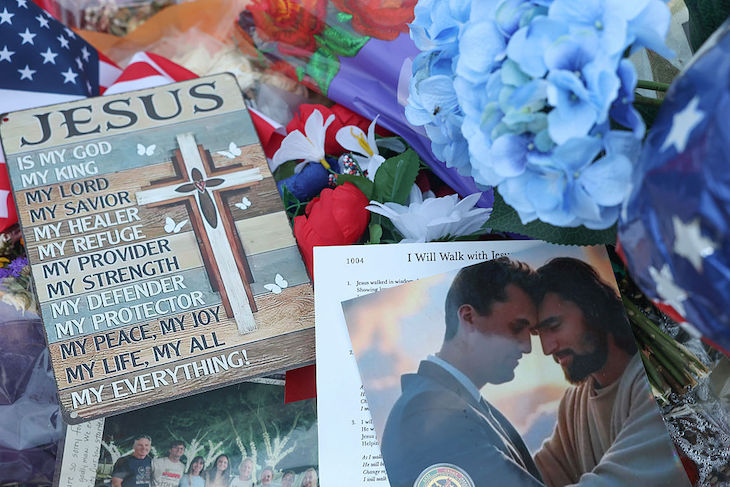

Kirk presented her late husband as a prophet, in the tradition of Isaiah, and a paragon of Christian commitment. And as a martyr: his last days echoed those of Jesus, she implied, for he fully surrendered himself to the will of God, even unto death. His death is now sparking a renewal of religion throughout the land, she said: many people have opened a Bible for the first time in years or have started going to church. In short, she spoke of him as a martyr and a saint.

As I say, it feels a bit wrong to comment on this. One should not speak ill of the dead, and in normal circumstances one should not question the speeches of grieving widows. But when claims like this are made, to millions, about someone who has just died, in the current febrile context, things are different.

It is surely legitimate for Christians, or indeed anyone, to challenge hagiography, to say that people should not, in general, suggest that their recently departed loved ones are saints or martyrs. Yet Kirk was certainly being presented as a Christian martyr.

Any such claim of martyrdom is complicated. Even when it seems pretty clear that someone was killed for professing Christianity, other factors may lurk, both in the victim and the killer. One should take great care. In this case, I suggest, it was not at all clear. Yes, Charlie Kirk was killed for his beliefs, for spreading them so powerfully. But his beliefs were a mix of religion and politics, and it seems that his killer may have seen his politics as more offensive than his religion. He saw Kirk as a spreader of hate, not primarily as a follower of Christ.

Imagine if a gay Christian campaigner were killed, and the killer’s motivation seemed to be homophobic. If his grieving widower presented him as a Christian martyr, I would have my doubts about the wisdom of that presentation. Yes, he was a Christian, but was his death really a direct echo of that of Jesus? His widower would surely be creating a pseudo-martyr for a semi-Christian cause.

But for Kirk, you may say, the Christian faith and the right-wing politics were inextricable. Yes, but it is right and proper for the rest of us to separate them. There are different socio-political versions of Christianity, and respect for Kirk’s memory should not pressure us into pretending otherwise. I see Christian nationalism as a defective version of Christianity. It claims that Christianity must be a powerful political movement, and it sees liberalism as the enemy. This involves reactionary positions on gender and sexuality – praise for the traditional family was central to Erika Kirk’s speech. ‘The greatest cause in Charlie’s life was trying to revive the American family’, she said at one point. Never mind that Jesus was a famously poor advocate of family values, failing utterly to model them in his own life, or to recommend family life to his followers.

Her forgiveness of her husband’s killer was certainly impressive. It was the emotional crescendo of her oration: she seemed to be doing the forgiving right there and then, as her voice faltered, and then flowed as if inspired. Even a narky liberal Christian like me can only admire that response. No one can fault her insistence that hate must be met with love. It is interesting that Trump, in his speech at the event, said that he couldn’t help hating his enemies (sorry, not sorry).

Of course his fans admire him for this, even the ardent Christian ones. For they want both responses to co-exist: a ruthless and realistic secular power, low on Christian charity, accompanied by the loving words of Jesus. In a way, this is fair enough: we need our political leaders to be realistic, often brutally so, even if we are Christians. But it is rare to see this duality embodied so neatly.

Erika Kirk made a powerful claim, that Christianity is currently being renewed as a political ideology, as America’s true creed. This claim is hardly new – of course she is carrying on the message of her late husband, and many others. But there is something uniquely powerful about her articulation of it. From her it has the force of a new revelation, born in blood. It’s as if Kirk’s death enables a new synthesis of religion and politics that was previously elusive. Those of us who take a different view of Christianity, who believe that political and social liberalism is the proper context of this religion, and that its alliance with nationalism is dangerous, should not be too polite to contest this.

Comments