America’s Montaigne, Gore Vidal, was born 100 years ago today. Born Eugene Luther Vidal, this Virgil of American populism entered the world on 3 October 1925 (‘Shepherds quaked’, he later said, describing his arrival in his typical, wildly egotistical way).

His father, Eugene Luther Vidal – after whom he was named – was a former quarterback, Olympian and the founder of three commercial airlines. While he worshipped his father, Vidal had a hateful relationship with his mother, Nina Gore, a beautiful monster who would go on to marry two more times following her divorce from Vidal senior.

Vidal’s formative friendship was with Nina’s father, Thomas Pryor Gore, the blind senator from Oklahoma. Young ‘Gene’ read him Voltaire, Gibbon, Shakespeare. He had read Livy in translation by the age of seven and attended his first presidential convention at 14, which was when he decided to drop ‘Eugene Luther’ and take ‘Gore’ as his first name.

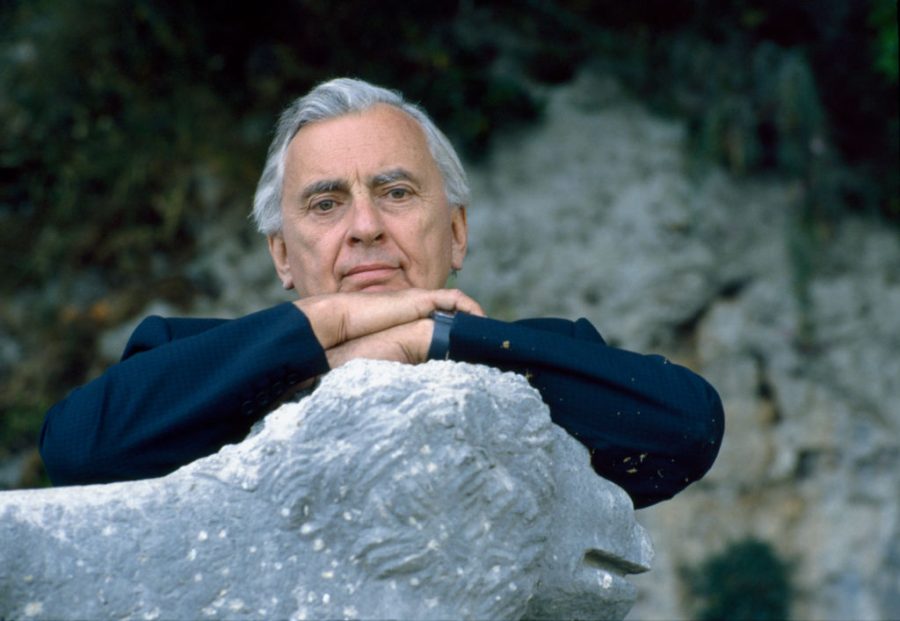

Vidal’s enduring handsomeness fed an unembarrassed narcissism

Enlisting in 1943 at the age of 18 during the second world war, Vidal served as a warrant officer aboard a freighter in the northern Pacific. This later inspired his first novel, Williwaw (1946), a Hemingway-esque tale of men at sea. He was heralded as a prodigy. But his next, The City and the Pillar (1948), the first serious American homosexual novel, proved divisive.

In need of money, having bought a Greek revival mansion in the Hudson Valley, Vidal began writing for television. He was a natural, commanding fees as high as $5,000 for a script. Writing the play The Best Man in 1960 inspired a bid for Congress in New York’s bedrock Republican 29th district. Despite help from Eleanor Roosevelt and the actress Joanne Woodward, he lost – but nevertheless managed to outpoll every previous Democratic candidate the district had had since 1910. His slogan ‘You get more with Gore’ had some force – not least given his claim that he had had 1,000 lovers by the time he was 25.

Vidal relished the fact that, following the breakdown of her second marriage, his mother was succeeded as Hugh D. Auchincloss’s wife by Janet Lee Bouvier, mother of Jacqueline Kennedy and Lee Radziwill. He would enjoy an easy relationship with John F. Kennedy but his brother Robert disliked and distrusted him. At a White House reception, he had upbraided Vidal for putting his arm around the First Lady (well, they had shared a step-father). The episode was inflamed by Truman Capote claiming a drunken Vidal had been evicted. Vidal successfully sued but his White House days were over.

Having been a mainstream liberal democrat, it was accepted that Vidal moved to the left in the mid Sixties, after his break with the Kennedys. There was his loathing of American ’empire’ and bankers, but he became a populist reactionary who believed his country had been injured by tyranny and foreign adventurism. Thus, the author Michael Lind believed he was more in the mould of his maverick Senator grandfather: that he moved not to the left but ‘to the South and West and back in time’. A final tilt at the Senate in 1982 also proved unsuccessful.

He relished enduring feuds with not just Capote but also the writers Norman Mailer, Truman Capote and William F. Buckley. His friendships, meanwhile, were eclectic: Woodward and her husband Paul Newman, the actresses Claire Bloom, Susan Sarandon and Joan Collins – and Princess Margaret. Later in life, he described himself as such:

I’m exactly as I appear. There is no warm, lovable person inside. Beneath my cold exterior, once you break the ice, you find cold water.

Yet, after an interview with this magazine’s Mary Wakefiled, he blew her a kiss. On interviewing Vidal at 70 for the New York Times, Andrew Solomon wrote:

His epigrammatic discourse – bred in equal measure of imagination, affectation and brilliance – is delivered in a voice as rich & smooth and alcoholic as zabaglione.

Given that voice and his patrician hauteur, the journalist Mark Lawson thought it a minor tragedy that no director had ever cast him as The Importance of Being Earnest’s Lady Bracknell.

On Labor Day in 1960, Vidal met his life partner, Howard Austen, a would-be pop singer with stage fright who became an advertising executive. Vidal claimed the union endured because it was sexless. In 1972, they bought a villa – La Rondinaia – on the Amalfi coast in Italy, perched on a cliff in the commune of Ravello. From this august exile, the historical Narratives of Empire series of novels appeared – the revolutionary era of Burr (1973) via Lincoln (1984) to Hollywood (1990) and The Golden Age (2000). Between them, they covered a century of American history.

Vidal’s self-mythologising memoirs, Palimpsest (1995) and Point To Point Navigation (2006), proved immensely readable but his legacy is his essays – self-assured, original, erudite, elegant and acerbic. His 1,300-page anthology, United States: Essays 1952-1995, is only two-thirds of his output.

The New York Times’s Charles McGrath believes Vidal will ‘live on most vividly on YouTube’. As Vidal himself used to say, ‘there are two things in life you should never turn down: the opportunity to have sex and the chance to appear on television.’

His enduring handsomeness fed an unembarrassed narcissism: ‘I have the face now of one of the later, briefer emperors.’ His Wildean bon-mots were usually unkind – but memorable: ‘A good deed never goes unpunished’ and his classic ‘Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little.’

A confidant of Tennessee Williams and a lover of Jack Kerouac, Vidal knew Christopher Isherwood, E.M. Forster, Albert Camus, Sartre, Anaïs Nin and William Faulkner. We know because he often said so. ‘Allen Ginsberg kissed my hand as Jean Genet looked on,’ he once said. And ‘I have never much enjoyed the company of writers – who are less famous than I am.’ Vidal’s philosophy? ‘There is not one human problem that could not be solved if people would simply do as I advise.’

Austen’s health forced a return home in 2003 to the Hollywood Hills. His death a few months later left Vidal bereft and a long, slow self-ruination followed. He died on 31 July 2012, aged 86.

So, Gore Vidal was human after all.

Comments