Ian Williams has narrated this article for you to listen to.

The antics of Keir Starmer and his top security adviser over the collapsed China espionage case bring to mind the slapstick British movie Carry On Spying – which is precisely the message it will have conveyed to Beijing. Instead of Bernard Cribbins, Kenneth Williams and their team of fictional incompetents, the real-life Whitehall farce has Jonathan Powell on a single-minded mission to appease China.

Powell, Starmer’s national security adviser, has been accused of torpedoing the trial to avoid embarrassing China at a time when he is leading efforts to rebuild diplomatic ties with Xi Jinping. One can only imagine the despair in Britain’s security agencies and the Crown Prosecution Service, who would not have brought the charges unless they were reasonably confident of success.

Britain’s intelligence agencies have become increasingly alarmed about the extent of Chinese espionage, which Ken McCallum, the head of MI5, has described as ‘a sustained campaign on a pretty epic scale’. The agencies say Beijing is now their top priority, and McCallum has warned that China’s spy agencies are playing a ‘long game’ to influence British public figures.

Multiple well-sourced reports last weekend described heated discussions chaired by Powell at which the Blair-era veteran effectively killed the espionage case. He argued that the prosecution needed to prove China was a ‘potential enemy’ and said Matthew Collins, his deputy, who was due to give evidence for the prosecution, could no longer argue this point as government policy now designated China a ‘challenge’ and not an ‘enemy’. The CPS then abruptly abandoned the case. The defendants, Christopher Cash, a parliamentary researcher, and Christopher Berry, who had both been charged under the Official Secrets Act, both denied allegations of passing secrets to China.

On Monday, a Downing Street spokesman denied Powell had chaired such a meeting, insisting that the government had not interfered in any way. But a day later, Stephen Parkinson, the director of public prosecutions, said the case had collapsed because the government had refused to provide evidence that China was a threat in spite of repeated requests over several months. Starmer then swiftly blamed the previous government for launching the prosecution without clarity on the threat posed by China – which seems a little rich, to say the least.

The trial would have provided a warning to Beijing about its rampant espionage, as well as giving an insight into its scale and manner, which in this case allegedly targeted the heart of British democracy. It is the potential fallout from these revelations, rather than any pedantic debate over the status of China, that best explains government qualms. It is hard not to conclude that the primary cause for the trial’s failure was a lack of political will and a desire to avoid upsetting China at a time when Starmer is prioritising economic and business links.

It is hard not to conclude that the primary cause was a desire to avoid upsetting Beijing

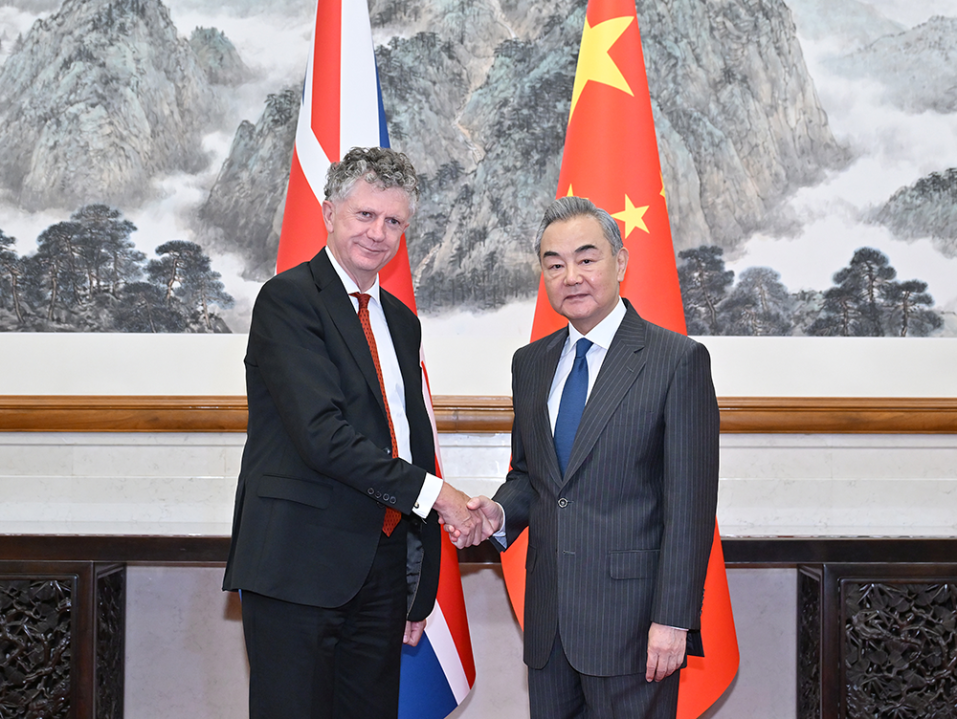

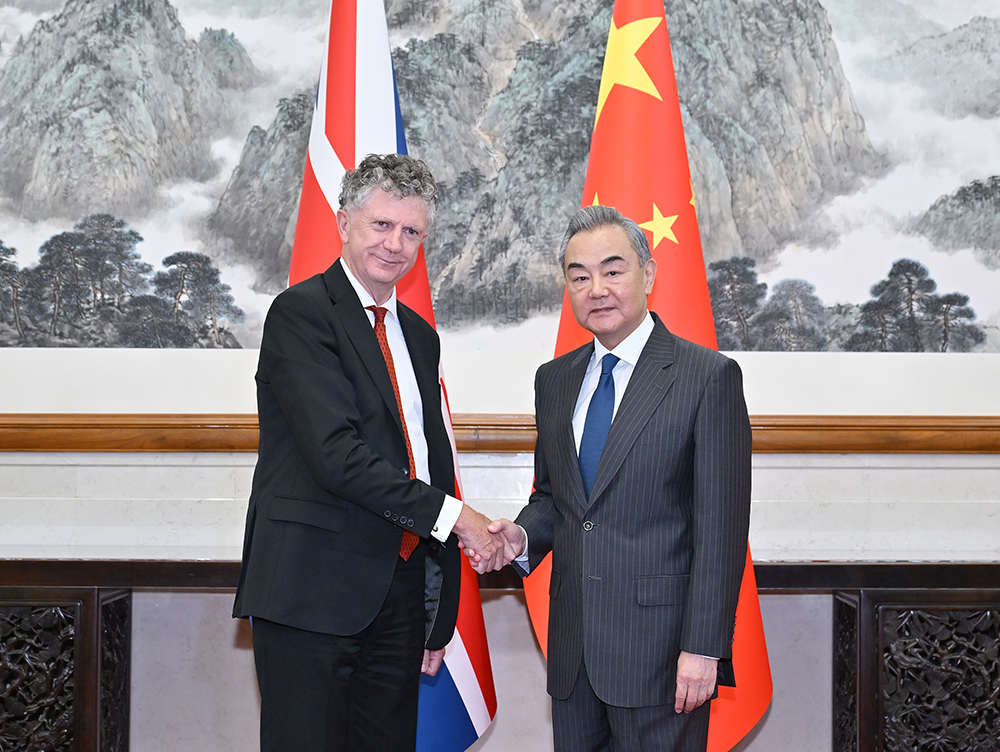

Whatever the precise machinations that led to the collapse of the prosecution, it is no surprise to see Powell at the heart of it. Since becoming national security adviser in December, Powell has taken control of what passes as China policy. His most recent low-key visit to Beijing was in July when he met top diplomat Wang Yi, telling him Britain was ‘willing to strengthen dialogue and communication with China and to work toward building a stable, pragmatic and long-term partnership’, according to China Daily.

On Powell’s watch, Labour has fudged a ‘China Audit’ that was supposed to bring clarity to policy, classifying the results. It has refused to place China in the top tier of new regulations designed to counter foreign influence operations. The Foreign Office has also reportedly pressed Sir Lindsay Hoyle, speaker of the House of Commons, to lift the ban on the Chinese ambassador entering parliament. A steady stream of ministers, now instructed to refer to China as a ‘challenge’ and not a threat, have gone cap in hand to Beijing, while efforts are being made to secure Starmer an audience with Xi.

Powell was chief of staff to prime minister Tony Blair from 1997 to 2007. He was an architect of the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland and is regarded as the ultimate foreign policy ‘fixer’, though his strong backing for Lord Mandelson to become US ambassador hardly suggests impeccable judgment. His China ties are less evident, although he helped negotiate the 1997 handover of Hong Kong. Out of government, he has been managing director of Morgan Stanley’s European investment banking business and CEO of Inter-Mediate, a charity he founded to work on conflict resolution around the world. The 48 Group Club, a discreet networking outfit whose stated mission is to ‘connect China to the world’ and which lobbies energetically on Beijing’s behalf, lists Powell among its fellows.

Chinese espionage has been likened to an enormous vacuum cleaner, hoovering up technology and know-how on a colossal scale. It encompasses multiple intelligence-gathering techniques, formal and informal, while at the same time seeking to manipulate western societies to serve the interests of the Chinese Communist party. Revelations late last year that the Duke of York employed an alleged Chinese spy as a business consultant provided further evidence of just how brazen Beijing has become.

Xi has turned China into a state defined by paranoia, where every organisation and individual is required by law to assist the security and intelligence services. They will have been deeply encouraged by the fiasco in London. And while the UK struggles to define Beijing as a threat, Xi has no problem describing western democracies as the enemy, flaunting his weapons in Tiananmen Square alongside ‘best friend’ Vladimir Putin.

A government decision over whether to allow China to build a mega-embassy on the site of the old Royal Mint in east London is expected this month. Opponents have dubbed it a ‘nest of spies’, and it has been opposed by the security services because of its proximity to sensitive communications cables. The Chinese authorities have reportedly resorted to periodically cutting off water supplies to the crumbling British embassy in Beijing as a way of applying pressure for approval. Opponents fear a secret deal has already been done, and on the evidence of the past few days, it is hard not to agree.

Comments