If New Labour was Margaret Thatcher’s greatest achievement, then Reform UK is perhaps Tony Blair’s. Distaste for the three-time election winner is a thread which connects much of the party’s leadership. Nigel Farage clashed with him at the European parliament in 2005. His deputy, Richard Tice, did the same as a Question Time audience member four years before. Their colleague Danny Kruger was once set to stand for the Tories against Blair in Sedgefield – but was forced out after promising a ‘creative destruction’ in public services.

Such ‘creative destruction’ is precisely the approach Reform wants to take to the post-Blair political world. Cambridge academic James Orr, the party’s latest recruit, is a leading enthusiast for a rollback of the post-1997 legal settlement, particularly the Human Rights Act and Equality Act. Tasked by Farage with building the intellectual pipeline for an incoming Reform government, Orr is part of a growing band of thinkers now clustering around the party and jostling for Farage’s ear. The aim is to ensure that, once in office, Reform does not become the mayfly of British politics, with the act of giving birth being what kills it.

‘Post-liberalism’ is perhaps the phrase that best encapsulates the various strands of thought in Reform. A shared animus for Blairism unites different figures. Orr is a champion of the ‘politics of national preference’, which stresses the primacy of the nation state and its citizens in policymaking, rather than multilateral institutions. Author Matt Goodwin – whose Substack has 87,000 subscribers and is enjoyed by many in party HQ – has been fleshing out a similar vision and shaping Reform’s thinking on migration. Some major party figures, such as Tice, have a more business-orientated focus of the world; others, like Zia Yusuf, are tech-enthusiasts. Both Kruger and Tim Montgomerie, the founder of Conservative Home, are Christians keen to develop the party’s social vision.

Ultimately, though, the primary force shaping Reform’s thinking remains Farage himself. His aides argue that, by sheer strength of personality, he has lashed and bound all these disparate strands into a proper political project. If Farage had not returned in May 2024, Reform would never have been able to attract the likes of Yusuf, Kruger or key staff in Millbank Tower. One ally argues that it is personal loyalty, not ideological purity, which keeps many of these people in politics: ‘Morgan McSweeney would be working in Labour without Starmer. None of these guys would be there without Nigel.’

The leader’s personal standing gives him maximum flexibility in how he chooses to respond to different political challenges. ‘He is not constrained by people walking around asking “What would Thatcher do?”,’ says an adviser, citing Farage’s pitch to post-industrial areas. Another ally argues that it is wrong to see him as following trends: ‘He is like a magnet, pulling others in his direction – Europe, mass migration, small boats, he was way ahead.’ Yusuf has compared Reform and Farage to Nvidia and Jensen Huang or Amazon and Jeff Bezos – founder-led companies which outmanoeuvre more corporate entities. A senior Tory is more sceptical: ‘Kemi’s challenge this past year has been party unity and Reform doesn’t have that problem – he tells them the policy and they follow.’

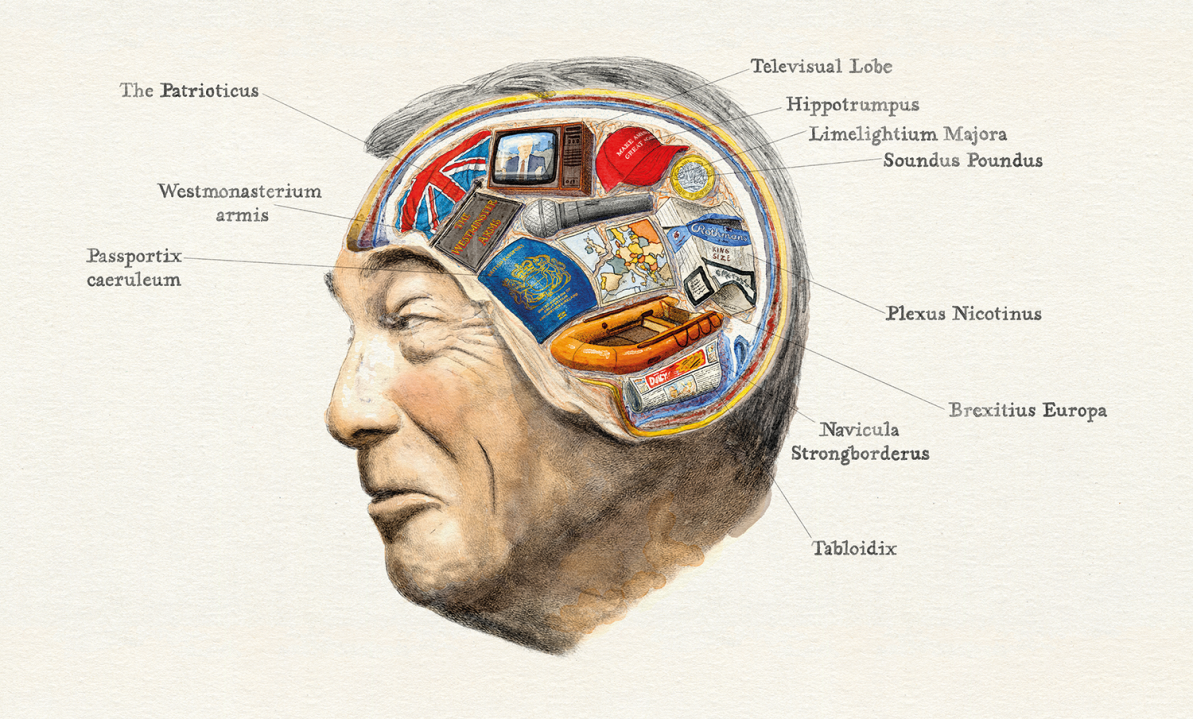

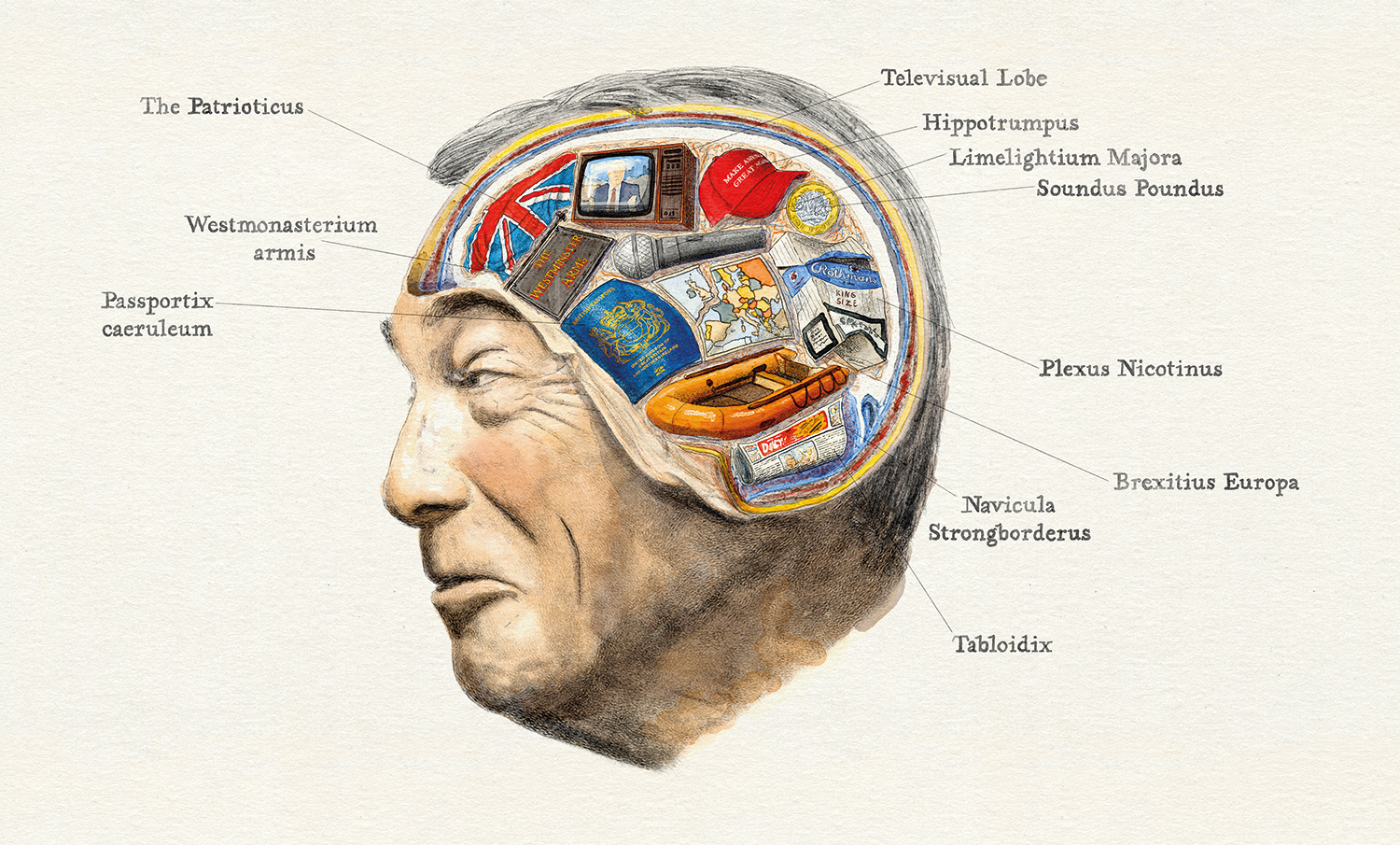

Though a deeply read man himself, Farage has never felt the need to surround himself with intellectuals. ‘He was always sceptical of the academics of the Anti-Common Market League,’ says a former colleague. ‘He thought they didn’t get it.’ His various projects – Ukip, the Brexit party and, previously, Reform – had neither the space nor inclination to launch their equivalent outfits of Labour’s Fabian Society or the Conservative Philosophy Group. Farage’s own thinking draws from many sources. His media diet is comprehensive; he prefers to read the newspapers cover to cover, rather than via selected handouts. Aides groan about a whirlwind of daily meetings, ranging from ambassadors to crypto bros, bombarding him with information from the City, Fleet Street and the Anglosphere.

Thinktanks are also playing their part. After signing on as Farage’s senior adviser, Orr dropped his roles at the Prosperity Institute (PI) and Centre for a Better Britain. ‘You can only serve one master,’ explains a Reformer. But PI, in particular, is well-regarded owing to its work on migration and leaving the European Convention on Human Rights. Many of Westminster’s established outlets are – rightly and wrongly – treated with deep suspicion within Reform. ‘They’re culpable in 14 years of failure,’ says one. The Centre for Social Justice, however, has escaped being tarred with the brush of failure. A newer outfit, Fix Britain – whose advisory board is chaired by Kruger’s former No. 10 colleague Munira Mirza – has its fans in Reform’s top team too.

Aides groan about a whirlwind of daily meetings, ranging from ambassadors to crypto bros

Internally, as the head of the Preparing for Government unit, Kruger reports to Yusuf on the board. Both take different approaches to the famous anecdote of Thatcher banging down a copy of Hayek and declaring to colleagues: ‘This is what we believe.’ Kruger devours Roger Scruton, Robert Putnam and Oren Cass; Yusuf prefers business strategies of first principles. Together, they are fleshing out the detail of Farage’s vision for 2029, with Kruger expected to unveil an update on his work next week. A platform is being drawn up for May’s elections in Wales, Scotland and London: the public services are expected to be a major focus, with 4,000 candidates now vetted. A never-ending round of breakfasts by Tice and others feeds in ideas and intelligence from the corporate world. Artificial intelligence helps, too, condensing legislation and policy into readable briefs.

Influences also come from abroad. Farage is a lifelong Atlanticist, for whom America has always held a powerful draw. Orr’s defection helps strengthen ties with Vice-President J.D. Vance, whom the Reform leader first met in 2012. People from Project 2025 – the pillar of Donald Trump’s second term – have been shuttling between London and Washington. Policy outlets such as the Heartland Institute and the Alliance Defending Freedom are keen to engage with Reform on issues like energy policy and free speech. Throughout his career Farage has largely resisted the ‘blood and forests’ right-wing ideas of continental Europe. But ‘pro-family’ social policies are now being examined – including Poland’s zero personal income tax for parents raising at least two children.

Next month, Farage will outline his economic philosophy, ahead of the Budget. He will claim the mantle of fiscal responsibility and ditch the £90 billion of tax cuts promised by the party’s ‘Our Contract With You’ document which he inherited on returning in May last year. That he can do this so easily speaks to his hold over the party and the seriousness with which he is taking the next election. Potential stumbling blocks – like his past comments on Russia – are being smoothed over. With the Tories keen to talk about the economy, Farage and his team want to move quickly to close down any breathing space for Badenoch’s party.

‘I have no desire to sit around the cabinet table in No. 10, no desire to have a ministerial title,’ Farage wrote in his 2015 book The Purple Revolution. ‘I have only been through the doors of No. 10 once when I was invited there in the 1990s – and once is enough.’ Ten years on, much has changed in British politics.

With Farage in Downing Street now a real possibility, the Tories have lost their monopoly as the political arm of right-wing thought. For the likes of Orr, a Farage triumph would represent a long-overdue victory for the ‘forces of conservatism’ which Blair so disdained. As the ex-Prime Minister once said himself: ‘A new dawn has broken, has it not?’

Comments