Next time you bite into a bar of chocolate, spare a thought for Ivory Coast. As the world’s largest supplier of cocoa, chances are the beans in your slab came from there. Elections, alas, have not been so sweet and with one due on Saturday 25 October, there are worries the protests, killings and all-out civil war that came in the wake of past votes could happen again.

President Alassane Ouattara, the incumbent, is 83 and seeking a fourth term under a constitution that, like the United States, allows just two. The Constitutional Council which vets all candidates for high office has barred most of the contenders, so Ouattara should cruise to victory.

Ivory Coast covers an area the size of Norway and its 31 million people speak around 70 different languages; religion is split almost equally between the Islam and Christianity and, even in good times, keeping the peace is a challenge.

For more than three decades after independence from France in 1960, Côte d’Ivoire as it’s known in French was ruled by Félix Houphouët-Boigny who banned all opposition but created the best economy in west Africa. On his watch, the country became what Goldman Sachs describes as a ‘swing state’, not beholden to any of the power blocks. As one African leader after another was overthrown in a coup, and thugs like Idi Amin and Robert Mugabe scared investors, the man still revered as ‘Papa Houphouët’ ran his own show, ignoring squabbles between Moscow and Washington, the Arab states and Israel, China and Taiwan. And he traded openly with apartheid South Africa: the rest of the continent, he said, were doing the same… in secret.

Tourists from Europe and the Americas filled beaches and hotel beds and, like Singapore under the late Lee Kwan Yew, Côte d’Ivoirewas safe, modern and an easy place to do business. London and Washington opened embassies shortly after independence and, more recently when Brexit happened, the government in Abidjan was among the first in Africa to sign a trade deal with Britain.

Alas, when Papa died in 1993, little thought had been given to succession. There were many keen to take over, but two men in their fifties filled the vacuum. Alassane Ouattara, a Muslim from the north, had served as prime minister under Houphouët-Boigny; Laurent Gbagbo, a Christian from the south, spent much of his life in exile from where he championed the cause of democracy.

There was a coup and a brief period of military rule, then elections in 2000 won by Gbagbo. Ouattara had been barred from standing amid false claims that he was born in Burkina Faso.

In 2002, the new government was almost overthrown in a revolt, and civil war took hold. A UN peace-keeping force restored order and elections that should have taken place in 2005 only happened in 2010; Ouattara, now allowed to stand, came first. Some 3,000 people died and half-a-million were made homeless by disputes that followed. Gbagbo was imprisoned for the part he played. Since then, Ouattara has been president, the nation’s diversity reflected in his marriage of 34 years to Dominique Claudine, Algerian by birth, white, and a Catholic of Jewish descent.

On his watch, the boom days of Houphouët-Boigny have returned. The economy is growing by 8 per cent a year and two-thirds of homes are on the grid, double that of neighbouring Liberia.

In 2015, the government went to the polls and was returned in an election the Guardian rated as free and fair. It was to have been Ouattara’s second and final term, but he stood again in 2020 and won an unconvincing 95 per cent of the vote. In truth, it was a one-horse race because the opposition staged a boycott.

In the meantime, the imprisoned Gbagbo had been sent for trial by the International Criminal Court at The Hague. He was acquitted and is home for the coming election but not allowed to stand due his original conviction. He and Simone have divorced, and she is running for president.

But the most prominent candidate was Tidjane Thiam, a relative youngster at 63 who has spent much of his life abroad. And therein lay the problem. Thiam had become a citizen of France, working as CEO of Credit Suisse. He left amid allegations that a secret surveillance system had been set up within the bank to spy on his fellow executives. Thiam denied wrongdoing but the board unanimously accepted his resignation. His bid to run for president collapsed when the Constitutional Council ruled he had only taken back his Ivorian nationality in 2025, too late to join the race.

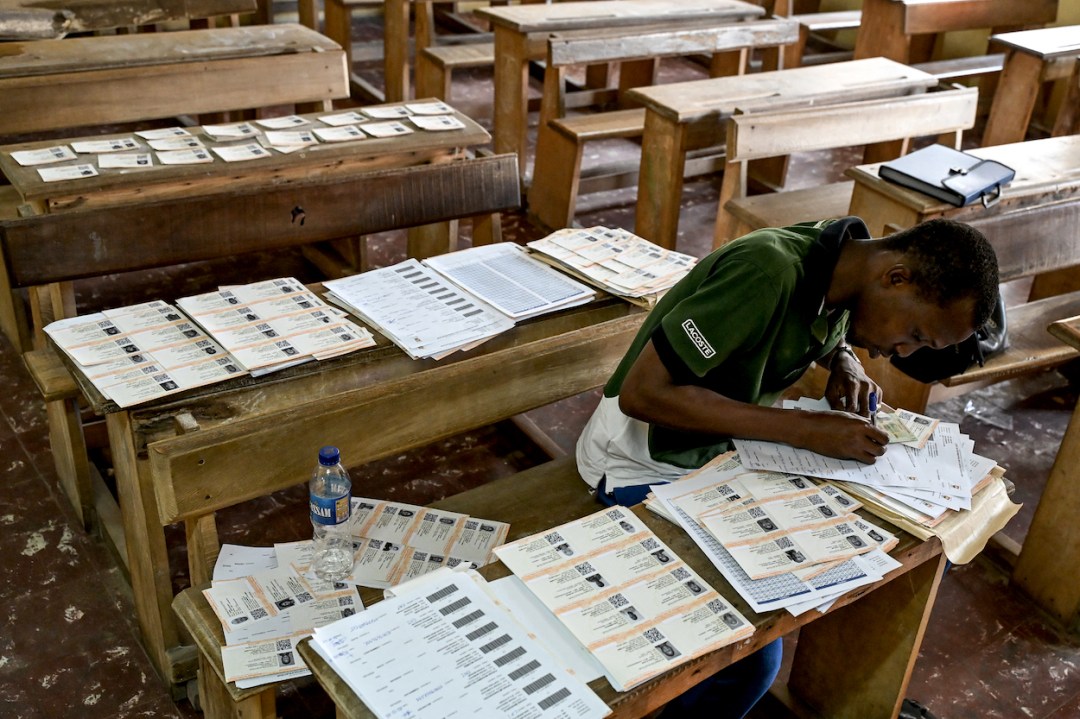

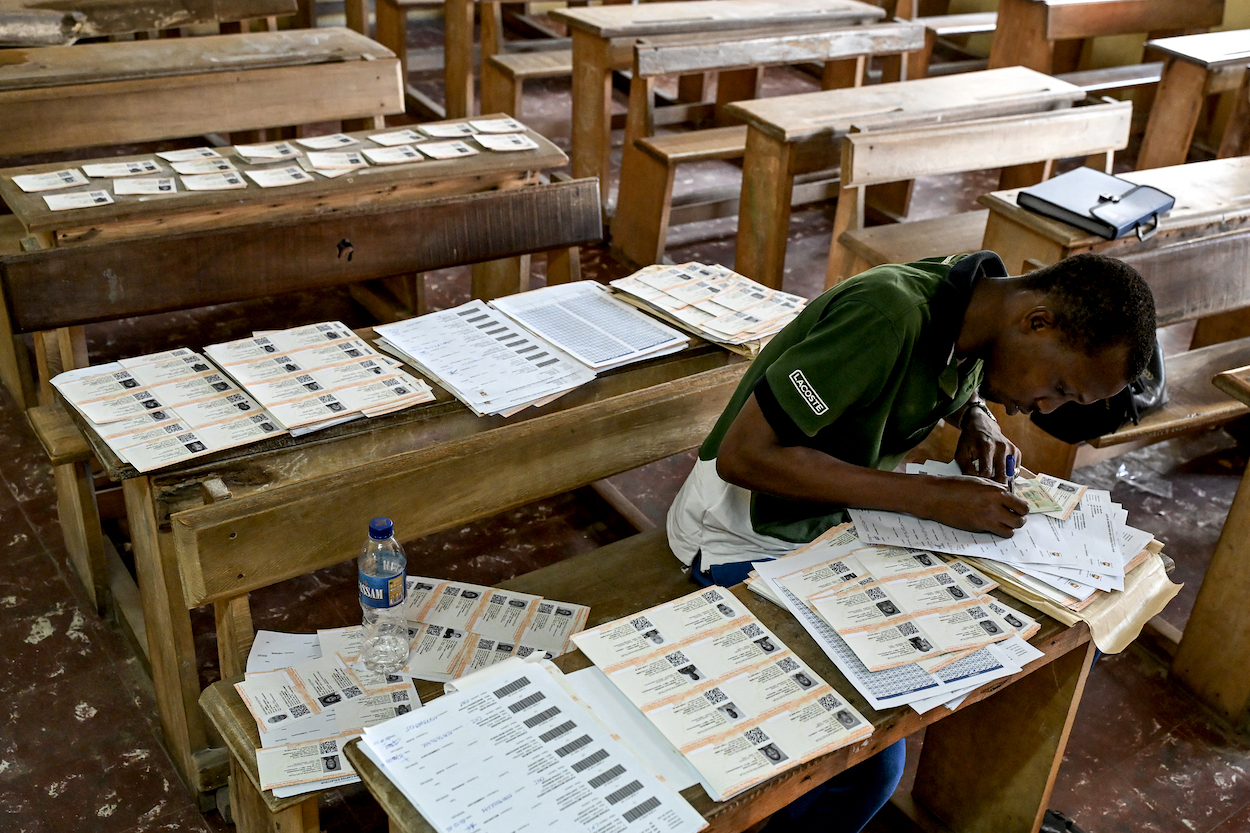

And that’s why the election could turn deadly. Messrs Thiam and Gbagbo have joined forces and brought thousands out in to protest against a fourth term for the president. To their credit, they have also encouraged a million new voters to register.

The chasm left by Felix Houphouët-Boigny has never been bridged

Since 2010, Côte d’Ivoire’s greatest achievement has been the jump in literacy, now close to 100 per cent. But in a country where more than half the population is under 30, school-leavers have come to the city in search of jobs that are not always there. Young and angry at their lot, some have followed the opposition onto the streets, mostly holding placards but others armed with clubs or machetes. Any hint the election was not fair could all-too easily be a call to war.

Ouattara’s age counts against him, but in September an election in Malawi saw the 85-year-old Peter Mutharika installed as president. In nearby Cameroon, 92-year President Paul Biya is still in power; when he first took office in 1975, Harold Wilson was in Downing Street, Gough Whitlam had yet to be dismissed in Australia and Jimmy Carter was running for the White House.

In a recent speech, Ouattara acknowledged a need, early in the new term, for dialogue with all sides. The chasm left by Felix Houphouët-Boigny has never been bridged and Ouattara’s legacy should be a nation united, and ready for a democracy where no person or party is shut out.

Now 80, Ggabgo can be part of that process, but to do so he must give up any hope of returning to the top job. The future belongs to the millions of young people who will be hoping for peace, and with it investment from abroad, growing an economy that’s diversified and less-dependent on cocoa, with wealth enough for all. For the old guard, that would be a legacy worth having.

Comments