Quietly, day-by-day, the inquiry into the Southport killings is revealing how disastrous failures of the British state led to Axel Rudakubana murdering young girls in August 2024. Yesterday it was the turn of the killer’s former headteacher, Joanne Hodson, to give evidence. She first met Rudakubana in 2019 when he enrolled at the Acorns School in Lancashire, aged 13. The boy was sent there after taking a knife into his previous school.

Acorns is a specialist school solely for children who have been permanently excluded from mainstream education. It’s also a good example of such a school, getting many of its pupils into work or further education after their time at Acorns. It’s also familiar with knives. Hodson said that ‘it’s not unusual for us to have pupils who come to us because they have brought knives into school’.

Hodson is highly-experienced with difficult or even dangerous children. This makes her evidence about Rudakubana all the more chilling. The headteacher said that from Rudakubana’s first day at Acorns, she could tell that he was ‘very high risk’.

So concerned was Hodson that she emailed staff telling them that the boy should be regularly searched for knives. This came after a meeting with the boy, at which she asked him why he had brought a knife into his previous school. According to Hodson, ‘he looked me in the eyes and said “to use it”, and he looked at me directly when he said it and I believed him’.

Rudakubana’s parents were also present at that meeting, and Hodson noted that they ‘completely accepted what he’d said without flinching’ at their son’s remark. The headteacher said that the boy’s parents believed he was a ‘good boy’ and that his behaviour was a result of him being bullied. Rudakubana’s father even said that at Acorns the boy was being bullied ‘like the boy in the other school’.

In reality, Rudakubana was clearly deeply paranoid. In one incident at Acorns he claimed to have been bullied by another boy who merely ‘told him to put his apron on’. Hodson was ‘very confident’ that Rudakubana was not being bullied, and clearly concerned that his parents would not challenge their son’s interpretation of events.

Following that meeting, Hodson wrote the email in which she warned staff about Rudakubana’. She remarked on his ‘sinister undertone’, that ‘there was never any sense of remorse or accountability for his actions’. It is worth repeating that Hodson is a highly-experienced professional, with many years of experience supporting children with very complex needs. So when she said ‘I’ve never come across a pupil like [Axel Rudakubana]’, we must take her seriously.

Unfortunately other professionals had different ideas. Hodson prepared an education plan for Rudakubana in which she described him as ‘sinister’ and ‘cold and calculating’. An unnamed mental health worker challenged this, accusing Hodson of racially profiling ‘a black boy with a knife’. The headteacher told the inquiry that the accusations ‘shut her up’ and ‘closed her down professionally’. Hodson agreed to remove those remarks from the plan, despite what she described as a ‘visceral sense of dread’ that Rudakubana was ‘building up to something’ and that she feared the boy would bring a knife to Acorns.

This is the sinister power of equality doctrine. Even highly experienced professionals feel cowed, doubt their own professional judgment and soften their language. To be thought ‘racist’ can end a career.

Did professionals suppress their judgements because of Khan’s race?

How many legitimate fears, concerns and warnings are kept quiet as a result? How many crimes, even killings, might be avoided if our culture encouraged professionals to see the world as it is, not as utopians wish it were? It is reminiscent of the Muslim child rape gangs, whose crimes were hidden or ignored for decades because people did not want to face the truth, lest reality ‘stir up community tensions’.

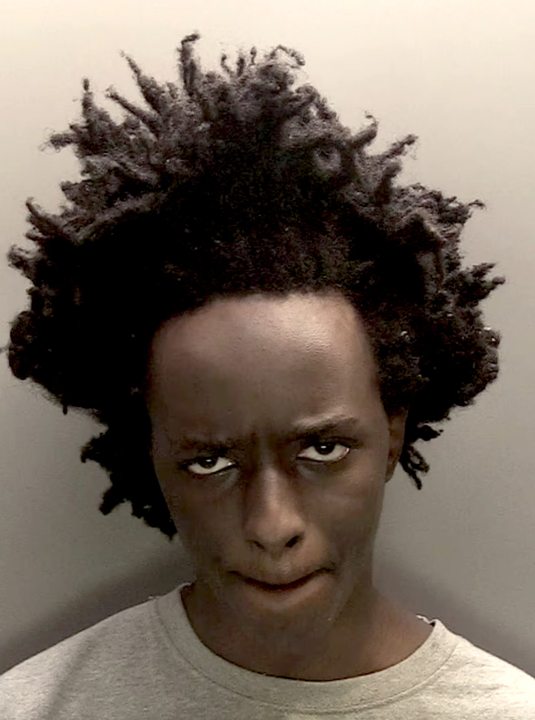

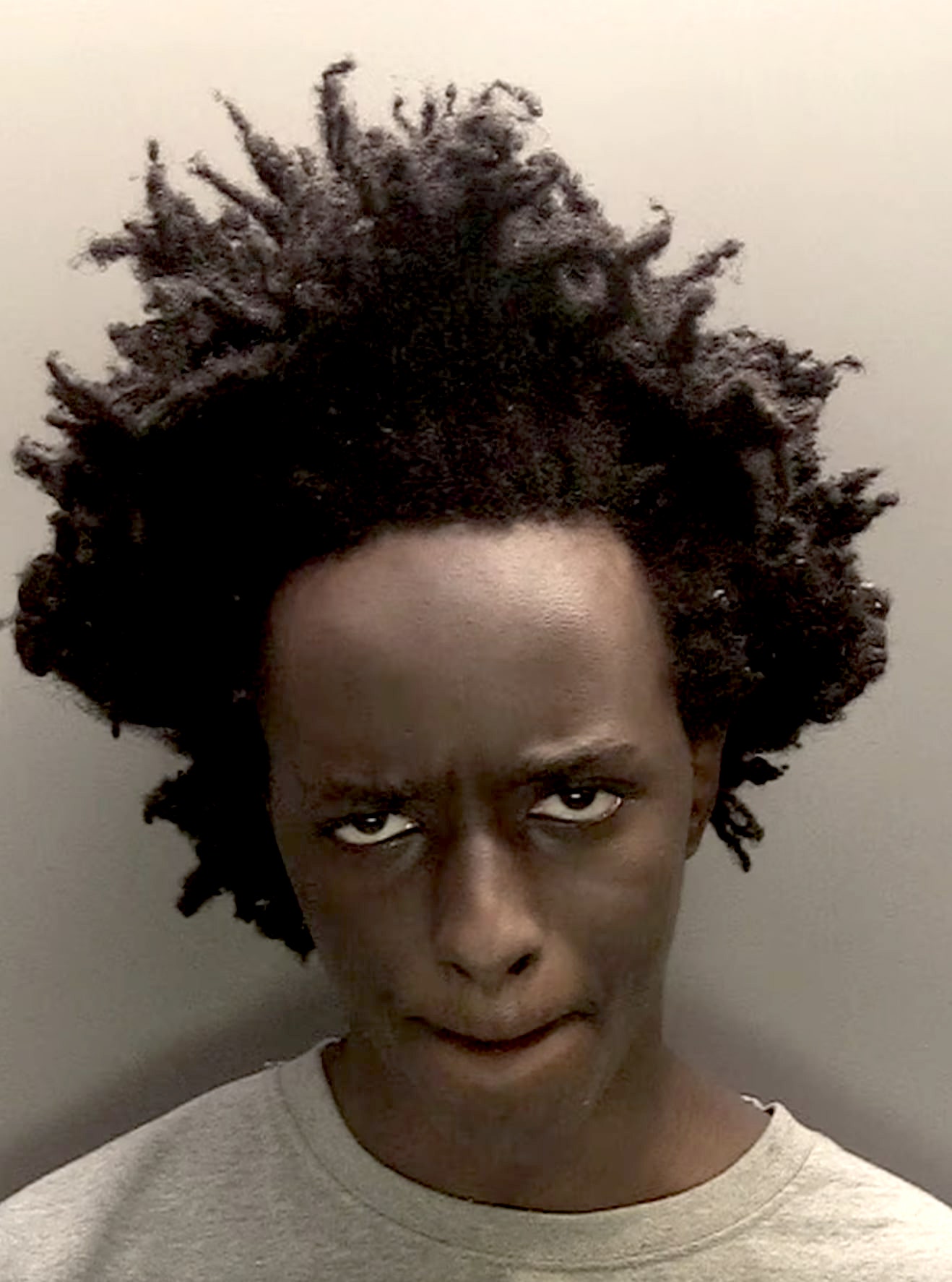

Does this culture of denial still exist? Just this week, Mohammed Umar Khan, 15, was sentenced to a minimum of 16 years in prison for his murder with a knife of Harvey Willgoose, another pupil at his school. Were there similar warning signs before Khan’s crime? Did professionals suppress their judgements because of Khan’s race? In light of the evidence from the Southport inquiry the whole education and child protection system has serious questions to answer, most importantly, are they more concerned with racial sensitivity than with preventing violence?

Comments