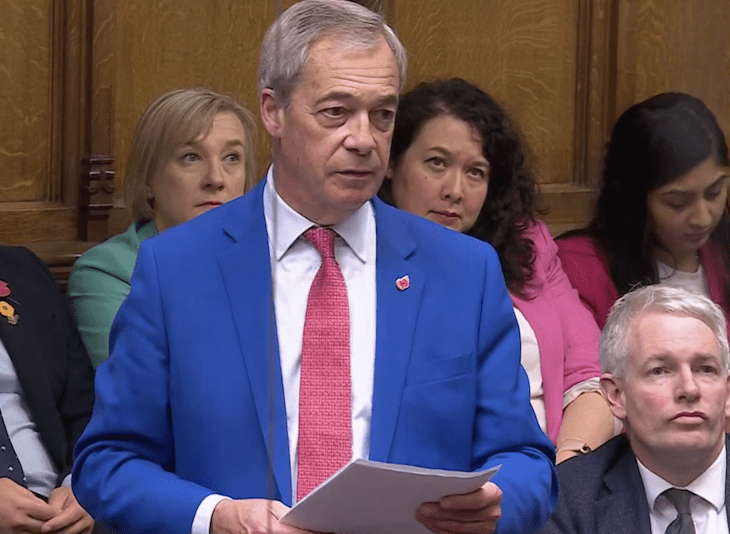

When Nigel Farage introduced a bill in the House of Commons requiring the UK to leave the ECHR (European Convention on Human Rights) this week, it was clear that something has changed in British politics. It wasn’t the absence of deluded heckling from Labour MPs or Lib Dem leader Ed Davey, both of which were fixtures of the debate. And, no: the Reform leader’s bill didn’t get anywhere. No-one expected it to, but that was not the point. Such bills are not generally taken as serious legislative proposals; they are more ballons d’essai to gauge reaction. And reading between the lines, the reaction to this one is both informative, and also encouraging to ECHR-sceptics. It demonstrated all too clearly that human rights scepticism is now mainstream.

Human rights lawyers may not like it, but there is now no going back to the days of passive acceptance of the ECHR as a fact of life

In a partially-filled Commons, the 96 who voted to allow the bill to proceed included 87 Conservatives; and despite some older Tories having strong reservations, none spoke against or voted with the Noes. Of course, ECHR exit is now official Tory policy; but nevertheless the fact that all but about 30 of their MPs turned out in support, led by Kemi Badenoch herself, matters. Ten-minute rule bills emanating from minority parties are frequently ignored; it would have been very understandable for the Tories, who have been desperately fighting Reform for months despite an embarrassing degree of agreement on many issues, judiciously to sit out this dance. Those refusing to rule out some kind of rapprochement between Conservatives and Reform may see their choice not to as a straw in the wind.

The Labour party, by contrast, clearly found itself in difficulty. Consistently with its policy of portraying Reform as an irrelevance, a tiresome horsefly to be swatted away if it came too close but otherwise ignored, the leadership sagely encouraged its backbenchers to abstain. This would have allowed the bill to be presented but then quietly die. Unfortunately, this tactic misfired. Backbenchers who felt strongly, including Stella Creasy, rebelled. Their view is that allowing Farage even a Pyrrhic victory would risk alienating a Europe that Keir Starmer is desperate to build bridges with. This argument was never entirely convincing; but the whips swallowed it, and said members could vote against if they felt inclined.

This may have been a mistake. A dignified disregard of the affair, coupled with a refusal of parliamentary time to take it further, would have sent a fairly unambiguous message to Europe about Labour’s intentions as regards the ECHR; it would also have satisfied many of Labour’s intellectual supporters. Instead, Labour has now revealed its weakness and division on the issue. Only 63 of its MPs out of more than 400 actually turned out to vote against the bill (the Lib Dems who accompanied them into the lobby actually outnumbered them by one). This is hardly a ringing endorsement of a pro-ECHR position, particularly given the sceptical noises made about the Convention made by Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood and the open secret that increasing numbers of Red Wall Labour MPs are close to supporting Reform’s position on the need to escape from it.

Whichever way Labour MPs turn, Wednesday’s vote has done an enormous amount to further the process of taking ECHR-exit from something seen as the rantings of a few crackpots to a feature of mainstream political discourse.

For one thing, the Conservatives voting in favour included numerous big hitters: Robert Jenrick, Chris Philp and James Cleverly, not to mention party intellectuals such as Nick Timothy and rising star Katie Lam. And they took with them many of the Ulster Unionists. Put another way, we can now say that the only parties remaining solidly and reliably in favour of the present human rights structure are the Lib Dems, the Greens and the Celtic nationalists.

For another, the episode nicely brought out the weakness of the arguments advanced by the latter. The only substantial speech against Farage, a rather pompous tirade by Ed Davey, showed this up well. He drew a rather facile comparison with Russia (which, it is worth remembering, started its onslaught against Ukraine abroad and dissent at home while still very much a member of the ECHR. It only quit the Convention when told that its position was untenable). He joined it to an irrelevant jibe against Donald Trump. The usual obligatory reference to the support of the original Convention by Winston Churchill’s post-war government – support actually fairly lukewarm, amounting largely to a feeling that the Convention was hot air that could do little harm and might as well be signed to avoid embarrassment – was followed by a reference to a number of changes introduced by the Convention which could perfectly well have been introduced by legislation here had there been a democratic political will for them.

Human rights lawyers may not like it, but there is now no going back to the days of passive acceptance of the ECHR as a fact of life. Human rights scepticism has moved out of the fringes, as much in Parliament as outside it, where thoughtful voters, including erstwhile Labour supporters, have increasingly begun to support it. Labour’s headache on this subject, one suspects, may be just beginning.

Comments