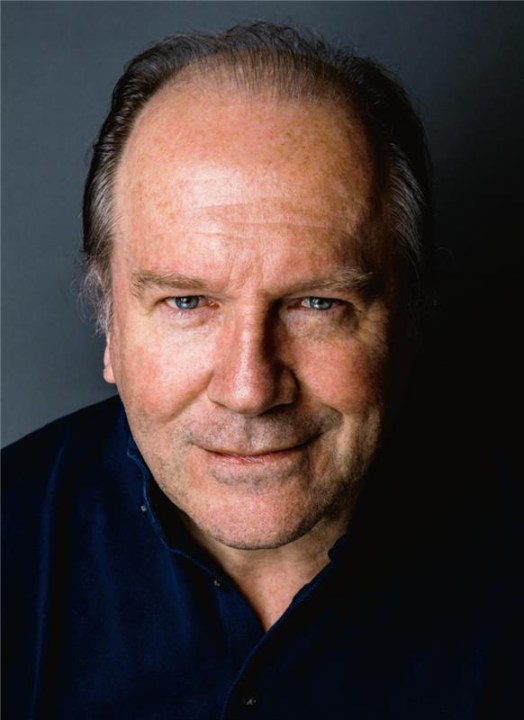

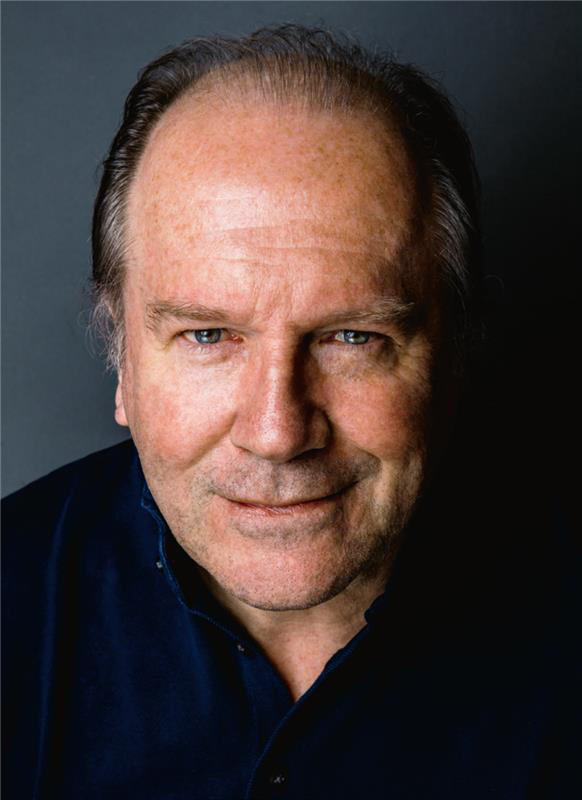

According to the literary critic Harold Bloom, male writers have daddy issues. So keenly do they feel the oppressive influence of their forefathers that when they take up the pen it is to use it as a sword. To produce something new, they must engage their predecessors in a writerly duel to the death. Bloom’s examples are all very highbrow – Blake vs Milton, Keats vs Shakespeare – but the theory applies across the literary spectrum. When William Boyd sits down to write a new spy novel and, removing his pen from its sheath, looks up to assess the field, it is (among others) the faces of Ian Fleming and John le Carré who stare back. What better way to deal with the anxiety of their influence than to create a spy who is not only reluctant but practically monogamous too.

Cue Gabriel Dax, a travel writer who had spying ‘thrust upon’ him in Boyd’s first novel of a projected trilogy, Gabriel’s Moon – and who, in The Predicament, is sucked further into the ‘quicksand’ of 1960s espionage life. Now a double agent, working for both MI6 and the KGB, and the only contact for a triple agent who is perilously embedded in the heart of Moscow, there is no way back to normal life for Dax – nor would he, being entirely honest with himself, wish there to be. In thrall to his handler, Faith Green, an older woman of cunning intelligence, sphinx-like in her fur coats, Dax is at her behest. No sooner has he retired to his new cottage in Sussex – paid for with wads of KGB cash – than Faith sends him off to Guatemala and then to West Berlin, where he uncovers a plot to assassinate President John F. Kennedy.

The eternal pleasure of reading Boyd is that you feel you’re in the hands of a writer who, in fact has no anxieties – of influence or any other kind. The Predicament is the work of someone who is entirely confident in their craft. We can see this in Boyd’s technical mastery – the precision of his descriptions, the perfect balance he strikes between comedy and tension – but we feel his assuredness most in his depictions of the human heart. It is as though he has somehow stolen a glimpse of that original forge where our discordant parts were melded into one by a reckless creator. As Dax has it, we’re part ‘brain’, part ‘animal’ – and what better place than a spy novel, with its acts of disguise and subterfuge, to explore the hopelessly divided self.

Comments