A foul-mouthed fantasist with a chin like an ironing board starts a wild conspiracy theory about the King’s brother. An alcoholic racing fanatic turns his gambler’s eye to the ballot box. A maniacal preacher gives such a polarising sermon that he paints himself as a second Christ and tours the country as a sex symbol. These are not the inventions of William Hogarth or Jonathan Swift; they are the figures who divided our political system in two, as George Owers tells us in his delightful new history of the birth of party politics. The Rage of Party traces the fevered rise of Whigs and Tories during the reigns of William III and Queen Anne. It is a period which most historians treat as too fiddly for a general audience; but in Owers’s hands it gets such a spirited retelling that even Hogarth and Swift would have approved.

The parties begin in the latter years of Charles II’s reign, when his brother and heir, James, converted to Roman Catholicism – a very bad political move in a country which defined itself by its Anglicanism. First in the Exclusion Crisis, and then in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, fervent Protestants urged the King to remove James from the line of succession, while High Church loyalists defended James’s right to rule. All involved were property-owning Protestant men who believed in England’s mixed constitution. But their debates about what kinds of Protestantism should be allowed, and consequently how much military support they owed their Calvinist Dutch allies in wars against Catholic France, cleaved them into two different worldviews. Tories were for church and country, and consequently peace; Whigs were for pan-European Protestantism, and therefore war.

The ensuing battle for power becomes an endless back-and-forth between Tories and Whigs; but what develops throughout is the entrenchment of partisan spirit. As politics enters ‘the crevices of everyday life’, Owers evokes an atmosphere of total culture war: which coffee houses you patronise, which wines you drink, which doctors or astrologers you consult, and, for women, on which cheek you wear your fashionable face patches, say everything about your affiliation. Voters are won over at election time with food, ale, money or promised positions; or, in the case of the Whig MP and founder of the original Spectator Richard Steele, with a cash prize for the baby born closest to nine months after the election – motivating wives to sleep with their husbands, in the hope that the grateful husbands will vote for him.

If there are any heroes in this story, they are the characters who try to steer a middle way. Queen Anne detested party politics and insisted on a mixed administration, although she was easily manipulated by her beloved favourites – first the passionate Whig Sarah Churchill, then the defiant Tory Abigail Masham. Robert Harley, her lord treasurer and proto-prime minister, spent his career trying to bring the moderates of both parties together. As Swift, Harley’s hired pen, lamented, Harley’s ministry was trapped in an endless sea-storm, with ‘the Whigs on one side, and violent Tories on the other. They are able seamen, but the tempest is too great, the ship too rotten, and the crew all against them.’ In the end, Harley seems to have had a nervous breakdown. The rage of party was too furious for anyone to control.

But then George I arrived from Hanover. Furious with the Tories for pulling out of the Dutch wars with France, he filled his ministry with Whigs, and there they stayed for most of the 18th century. Arguably they still govern us today. By founding the Bank of England and the City of London to fund their wars, they created our financial system: indeed, our economy is ‘far more financialised than even the most sophisticated Whig of the 1690s could have ever dreamed of’. With this battle won, the parties evolved into Conservatives and Liberals; then gave way to Conservative and Labour, as the voting franchise extended and priorities shifted towards the distribution of wealth.

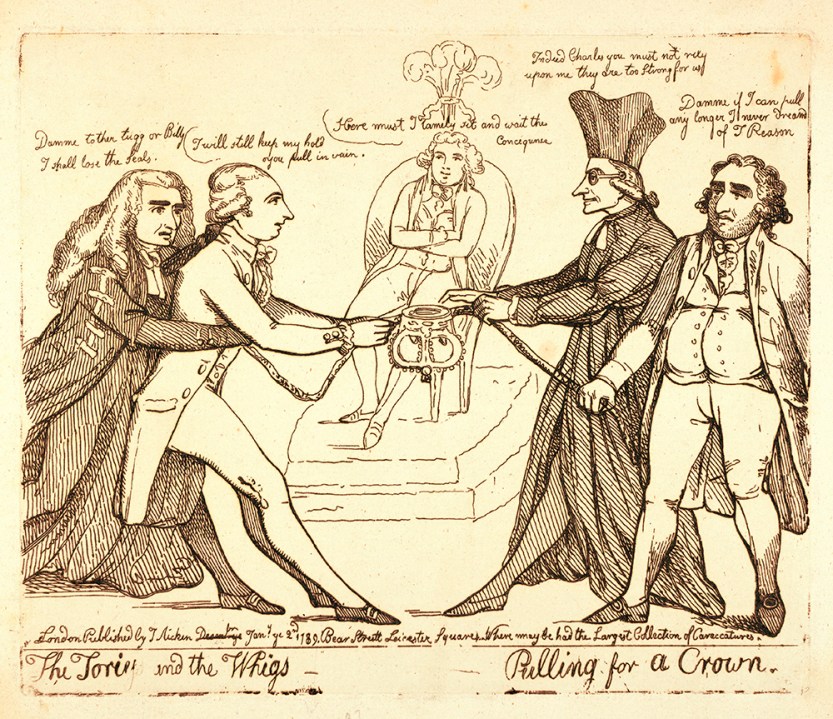

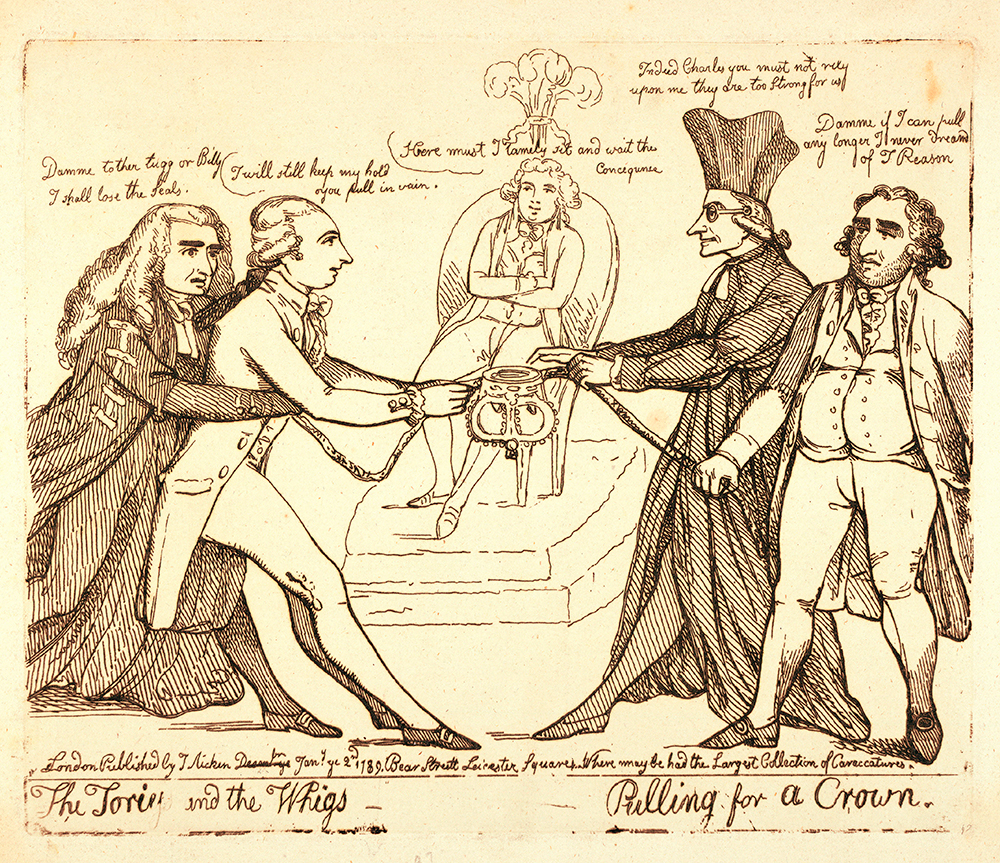

If Owers had filed his book a few months later, however, he might have qualified his reminder that the Whig-Tory divide ‘doesn’t map very neatly on to 21st-century party politics’. Increasingly it seems like a very relevant party divide indeed, especially in their debates on nationalism, immigration, and safeguarding the country’s institutions. Tories and Whigs map almost exactly on to the ‘Somewheres’ and ‘Anywheres’ identified by David Goodhart, and nowadays on to Reform and its centrist opposition, whether Labour or Conservative. There is a suggestion in this book that British politics is at heart less about economic policy than about an existential tug-of-war of national identity. There could be no better time for a detailed and ambitious history of that period – especially one which is so entertaining.

Comments