One of the greatest dangers posed by the government’s curriculum review is that it will result in children abandoning more demanding subjects such as history, geography and languages at GCSE. This is the fear voiced by a number of educationists, including Baroness Spielman, the former chief of inspector at Ofsted, who said that scrapping the English Baccalaureate would be a ‘death blow to secondary languages teaching.’

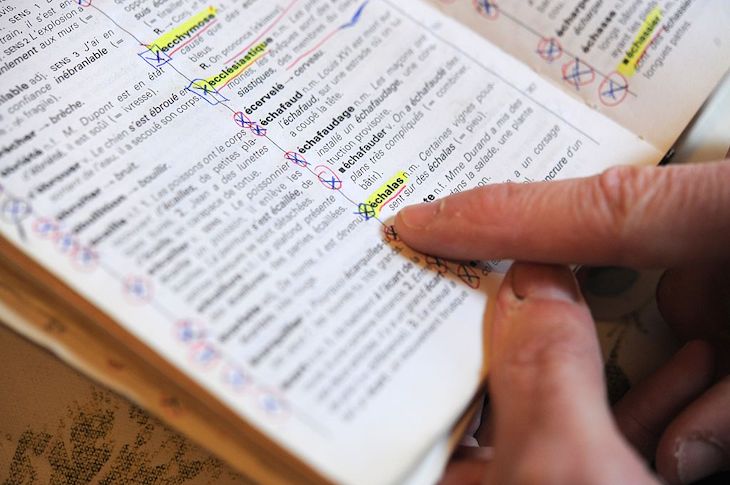

Learning to read, write and speak a foreign language is not only a ‘skill’. It’s about learning how to think differently and think better

This, alas, merely reflects a longer-term malaise: teaching the adults of tomorrow how to speak – and think – in a second language. This requisite has always been a low priority for technocrats and philistines in general, for whom learning a foreign language is redundant in a world where everyone speaks English. This discipline also makes a second transgression against modern mores: it’s difficult. This is taboo for certain types who would prefer it if everything were ‘accessible’, ‘inclusive’ and ‘relevant’, – or easy.

Yet learning to read, write and speak a foreign language is not only a utilitarian enterprise, a mere ‘skill’. It’s about learning how to think differently, and to think better.

Centuries before modern educationists became obsessed with ‘critical thinking’, pupils in this country who were taught Latin or French learnt the hard way – as they should – that these strange tongues do this in abundance already. Learning a foreign language strengthens cognitive abilities in myriad ways, from honing your capacity for logic, appreciating nuance and recognising where norms don’t apply, to teaching you the rules of grammar and, in time, coming to recognise what every single word in a sentence does.

Grammar hasn’t been taught comprehensively or rigorously in the public sector for at least two generations, and like most people educated in a comprehensive or grant-maintained school I only came to fully understand the rules of English via French lessons. This was where, for example, we were taught the difference between the imperfect, perfect and pluperfect tense, the difference between ‘me’ and ‘myself’, and the perverse norm that the most common verbs are also irregular. In other words, learning a language entails and encourages the facility of thinking with clarity, precision and vigilance. I was once told that the pupils in her school who were the best at parsing at English were also the best Latin scholars. This is unsurprising, as in Latin it’s essential to recognise the form and know the function of every word.

Yet being taught a foreign language is more than sharpening one’s mental skills. Even for an 11-year-old sitting down to his or her first French lesson, it becomes soon apparent that they’re entering into a different mental universe, to a land where inanimate objects can be male or female, where there are two ways to address someone else as ‘you’. In French, it transpired, there are even two difference ways to ‘know’, depending upon whether you are referring to information or a person.

That distinction, lacking common English parlance, is a useful one, and our language’s inability to distinguish between ‘you’ singular or plural anymore reflects another shortcoming. But we needn’t feel abashed. ‘You’ is famously democratic, and at least we have the equally concise ‘his’ and ‘her’, rather than the cumbersome ‘what belongs to the masculine or feminine thing’.

That’s one of the most delightful side-effects about learning another language: you learn more about your own. As an adult I progressed to Italian, and went further than my GCSE French had taken me, to the point where I encountered the forbidding subjunctive. I hadn’t even known there was such a thing. Discovering that there was a whole way of expressing something that was hypothetically true, or you wished it was true, was a revelation, as was finding out that the mood existed in English today only in vestigial form, in ‘if I were you’ or ‘so be it.’ Our language seems sadly bereft for having lost a dedicated means through which to express uncertainty and desire.

That’s not to say English is ‘inferior’ for it. Language is one area where cultural relativism can’t be gainsaid. People just say and do things differently and there’s no right or wrong way. If you are (un)lucky enough to progress onto German, you learn that there they have a third gender, that words have a routinely mysterious way of jumping around, and that they will always at the very end of the sentence the second verb put. If you are reared and marinated in the atmosphere of Romance languages, with all their beauty and simple predictability, the illogicality of German comes as a shock. Yet that remains intrinsic to its exotic allure: the harder the challenge, the more rewarding it is rising to that challenge.

That’s the abiding lesson language-learning has taught me, and it’s something that should be drilled into every child: the more you put it, the more you get out.

Comments