With the Tobacco and Vapes Bill travelling through the House of Lords, I think it’s high time we looked at the data justifying this almost unprecedented assault on liberty. Public health lobbyists and their politicians argue that without the incoming Generational Smoking Ban, smoking would continue to be prevalent amongst young people (16-24), which is when the vast majority of smokers initiate their lifetime consumption habit.

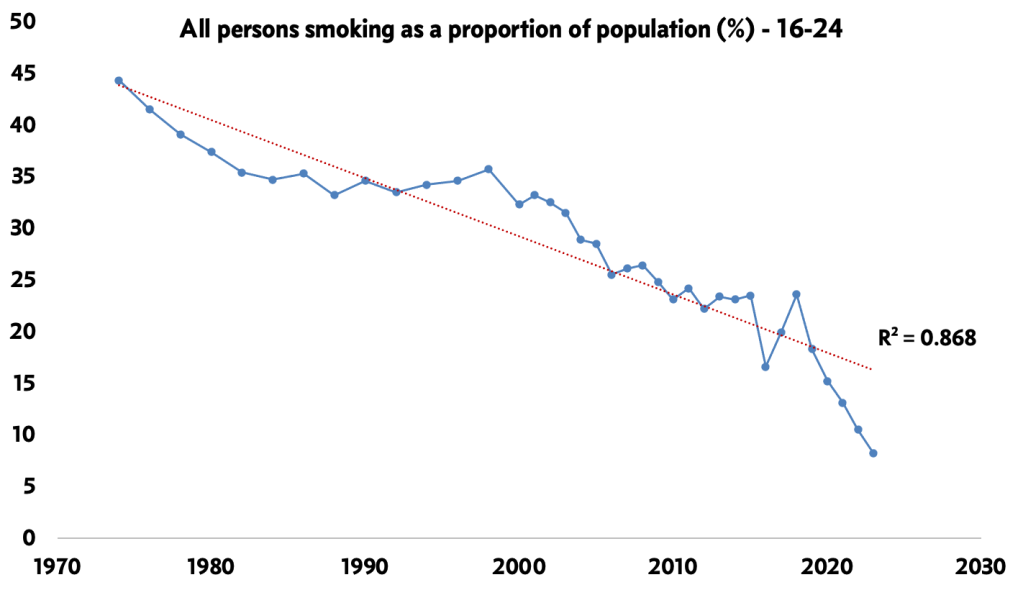

So, what happens to this argument – the fundamental argument behind the Generational Tobacco and Vapes BIll – when we look at the data provided by the ONS? Look at the graph below.

It turns out that this ‘onboarding’ rate is falling dramatically in recent years amongst young people. In 2020, as lockdown was first introduced, smoking amongst young people skyrocketed to 23.6 perc cent of the youth population (the author is included there) – in 2023, that has fallen to 8.2 per cent. It is on track to fall even further – achieving a ‘smoke free’ rate within the next few years by about the time the legislation comes into force in 2027. Modelling forward with a linear trend, we can see that by 2027, current 18-24s will be smoke free. By 2033, 25-34s reach smoke free, even if they are not affected by the proposed ban.

Some have pointed to the indoor smoking ban as the key catalyst in this, as shown by the Institute for Government’s fawning analysis over the TBV here. However, their own data shows, it barely made a dent in the declining rate of smoking. So I think it’s best to dismiss that argument.

Let’s look to the price of tobacco to explain the decrease. Since the 1970s, tobacco prices have made up a greater share of household baskets, rising from less than 1 per cent of the household basket of goods to around 3 per cent today -–so it is clear that prices have had a role to play in the decreasing smoking rate. However, it is not the price of tobacco, per se, which has been leading households through their consumption habits, but rather, the price of nicotine.

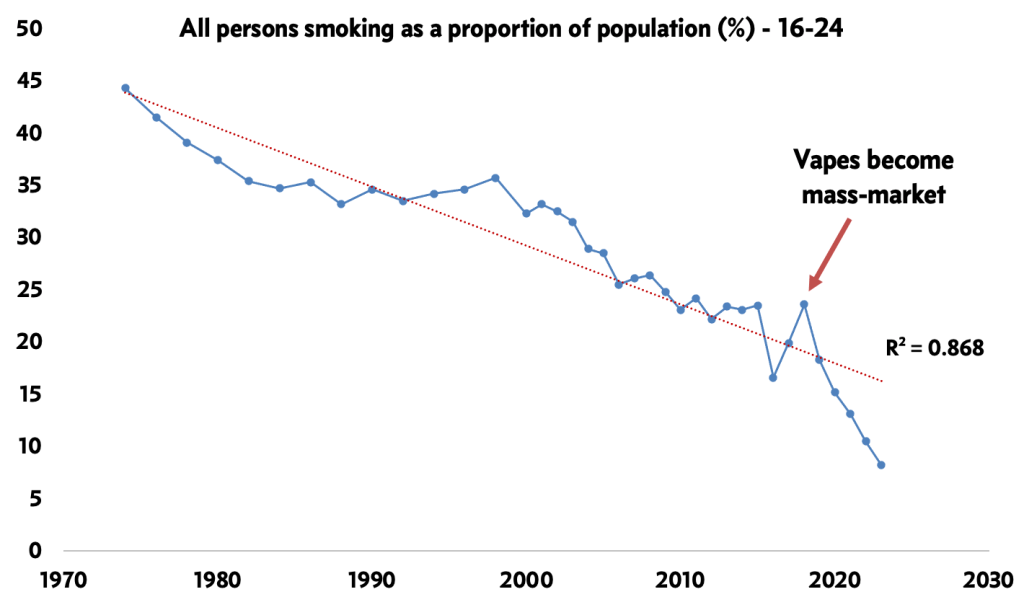

The arrival of vapes, pouches, heated tobacco, and gums onto the market has significantly displaced the role of tobacco in nicotine delivery, and thus, accelerated the decline in smoking. In 2018, Juul had begun to make traction – by 2019/20, cheap disposable vapes had entered the market and proliferated.

The increase in vape usage by young people is regrettable, of course. However, in cases where the choice is between highly carcinogenic products (cigarettes) and products rated over 95 per cent safer (vapes, pouches, heated tobacco etc), I’d much rather young people consume the latter. Am I endorsing the often illegal consumption of these products? No, absolutely not. But if there are only two choices between them, the safer option is superior.

We can see why vapes are becoming much more popular than cigarettes – they are cheaper (people are only really paying for the nicotine), they have fewer unpleasant odours (who wants to smell of smoke all day?), they don’t require a lighter or other auxiliary equipment and, most importantly, they taste much nicer than cigarettes or tobacco. That is why there are as many vapers as there are smokers in the UK, and the number isn’t trending in tobacco’s favour.

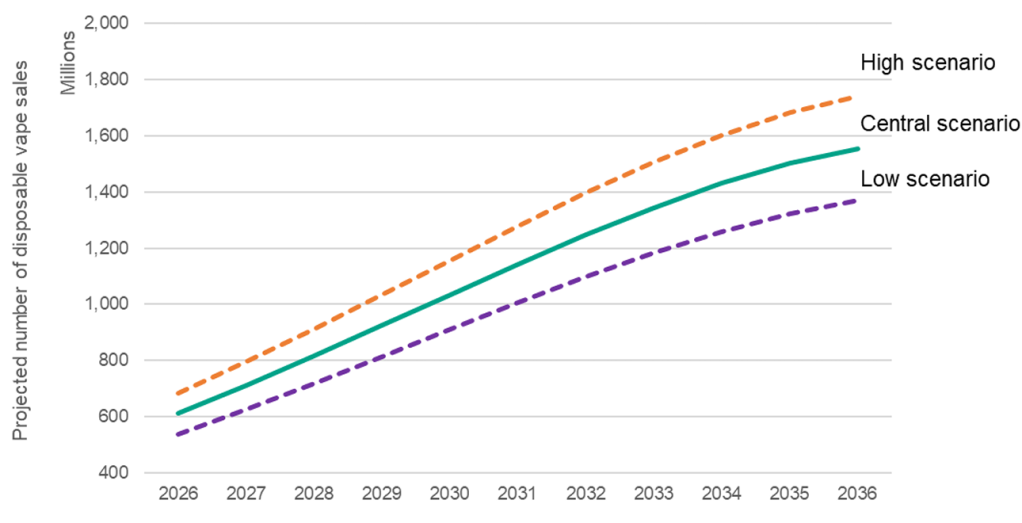

Back to the generational smoking ban. With the rate of new smokers hurtling towards smoke-free, what is the point of such a ban? We can see from Figure 3 above that the number of vapes is trending upwards, at the expense of tobacco consumption. Not only will there be an organic fall in new smokers over the coming years, but an increase in tobacco harm reduction products shifting smokers away from cigarettes. We know from research by UCL that new starts on tobacco are less likely by 5.4 per cent and 14.4 percent over 18 months and 48 months as young people age – so the ban is in itself nullified over the long run.

The enforcement of a ban is thus an unnecessary increase in limited resource expenditure; an increase in Trading Standards budgets by £100m over 5 years will not suffice to counteract the surge in black market tobacco currently taking hold across the country. Despite recent press pushes, the duty collected for cigarettes has fallen by 44.4 per cent over 4 years, indicating an explosion in criminal activity. Indeed, Welsh Trading Standards have now come out and opposed the concept of the Ban, primarily grounding its criticism in its enforceability over the long-run (although they have since reneged on their statement, assumingly under pressure from higher-ups).

Much ink has been spilled over the immorality of the generational smoking ban, but the data makes the argument clear – this is a pointless ban, which will only end up costing money at the expense of liberty.

Comments