Here’s a question for you to contemplate, this Remembrance Day: If you found yourself in the chaos of a terrorist attack, or if your child was kidnapped, who would you most like to come to the rescue?

My particular hope is that the Prime Minister and his Attorney General, Lord Hermer, consider this question, because the honest answer has to be that they’d want men like the one sitting in front of me now, staring out at the grey north sea: George Simm, former Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) of the 22 Special Air Service (SAS).

George Simm’s love affair isn’t actually over. He’s still fighting for the SAS and thank God he is

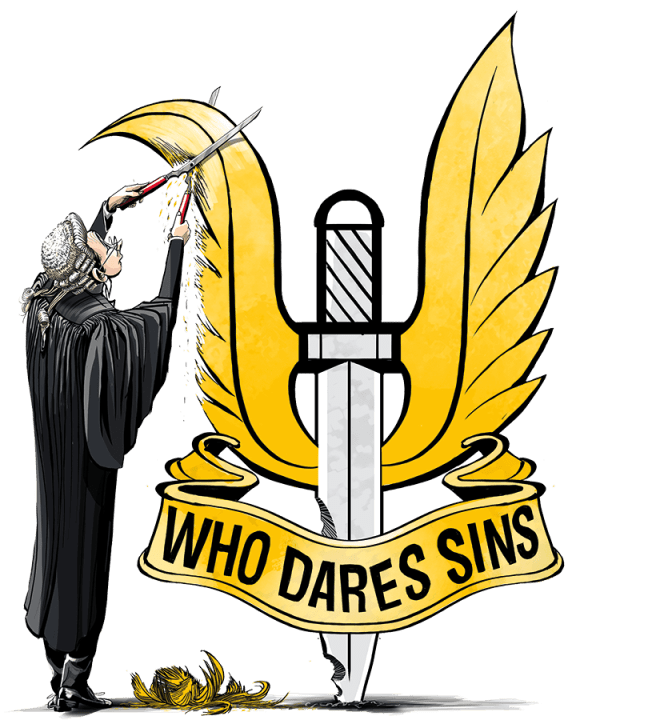

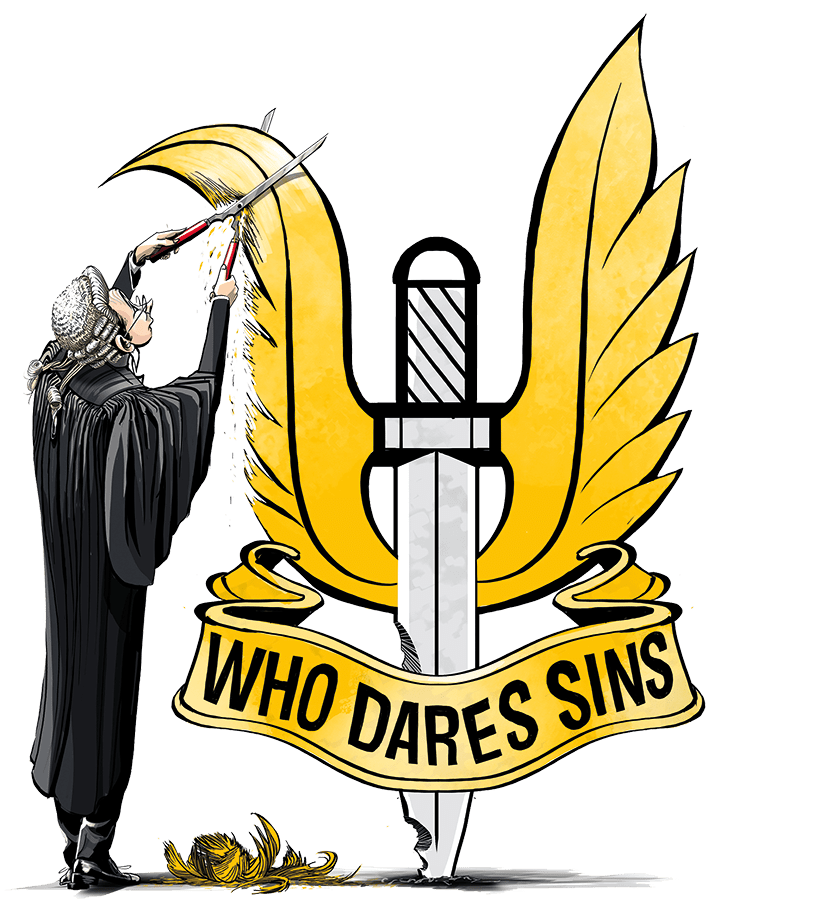

And then they’d have to wonder why they are presiding over the slow destruction of our Special Forces, without seeming to give much of a fig. Our most capable soldiers increasingly find themselves in court, partly because of the Human Rights Act, for actions that once won them medals for bravery, and this rolling boil of legal cases, is undermining not just the SAS, but the entire army. Who’d sign up, knowing that simply following orders might land them in prison? And what will happen to this country when there’s no force of last resort?

The SAS as a rule, stay schtum, but yesterday nine four-star generals signed an open letter accusing the Prime Minister of allowing human rights law to undermine the effectiveness of Britain’s armed forces. It’s the same message Simm and Former Commanding Officer of 22 SAS, Richard Williams have been so urgently trying to convey. I look out through the window as Simm talks, at my son and his friends hitting golf balls on the grass and what I feel most is fear for their future.

How have we got here? I ask Simm. How can this government be so indifferent? Is it some sort of conspiracy to undermine Britain? Simm laughs. ‘There’s no conspiracy! It’s mostly incompetence…that and the narcissism of politicians. That said, amongst the current lot in power, there’s definitely an obsession with internationalism and distaste for the nation state. And the trouble is,’ he says, ‘you can’t be loyal to both the nation and some weird idea of an international order. You can’t pay for welfare and then suddenly say to everybody, yeah, come and get some…Tell your boy that he needs to stand back from that golf club or he’ll get hit.’

George sees everything.

To grasp what we stand to lose if the SAS is defanged and depleted, it’s useful to understand what an SAS man is, to know the story of someone like George Simm. George grew up just a few miles away, in a mining community on the Northumbrian coast. He was unusual, tough-minded and independent, but the community itself seems the bedrock of what he became. ‘My father was injured in the mine when his brother was killed. It was a cable snap,’ says Simm. ‘It was a tough life but you grow into your conditions and that was the essence of the community. The character and nature of people was tight, very principled. It was a value based society and any time anything went slightly awry it was dealt with PDQ. You get high take up from that sort of community when the country says we need men to fight,’ says Simm. ‘Because we know what the right thing to do is.’

Simm passed the exams into grammar school but refused to go, and ended up eventually in the army Junior Leaders Academy, which takes bright kids and trains them in the officer syllabus.

‘I followed my instinct,’ he tells me. ‘A lot of what I did in life was always instinctive. I used to say to a lot of our young recruits: trust your instincts! Your brain is absorbing so much data without you being aware of it, and that information is fed to you as instinct.’

‘Tony Blair was wrong from the beginning’

Of the Academy, Simm says: ‘You have all these kids with flat vowels from all over the country, working class kids obviously with a bit about them, grammar school material but with a military bent. General Jackson, Mike Jackson called us the Jesuits which was very apt!’

‘I hate bullies,’ says Simm, several times during our interview. Former CO Richard Williams, sometimes quotes Einstein: ‘Only a life lived for others is a life worthwhile.’

Once in the SAS, ‘I felt, whoa, this is just like, ‘Let me out!’ says Simm, his eyes bright. ‘There were some cracking soldiers and some cracking commanders and you start to get an essence of what special means because it’s so radically different from anything you’ve experienced in life. Suddenly you’ve joined this unique little group and you go, ‘Am I good enough for this?’ Yes, I am and I’m going to show you.’

Perhaps the best and the most heart-breaking example of what the SAS can do was in Northern Ireland, where they were deployed to combat the IRA. Best, because as Simm explains, they took on an entrenched and depressing situation and transformed it. Heart-breaking because of what it’s come to: old soldiers hauled up on murder charges, their lives ruined at the behest of people who hobnob with own Attorney General.

‘What you have to understand,’ says Simm, as he begins my briefing on Northern Ireland, ‘Is that the IRA was primarily a criminal organisation. Yes, I know where it started, in the 1798 Irish Republican Brotherhood, the whole anti-British thing but their aims weren’t achievable, so what they became was an organised crime group controlling the rackets: the drugs, the prostitution. To a degree that’s what they’ve done since with Sinn Fein. They just turned an organised crime group into a bloody political party.’

So, in no conceivable sense are they freedom fighters?

There’s another Remembrance Day question for Lord Hermer, though I dread to think what his answer would be

‘No, no, no. It’s a fallacy. Think about it. The government has to have the monopoly of violence, that’s just a given. And there is no other army in the world, none, that could have done what we did there. The peace was won by young working class soldiers with public school snot-nosed officers, working together. The men and women in the RUC are extraordinary people but the fact was that they couldn’t function properly so the army held it until they got to a point in about ’83/’84 where they could say, okay we’ve got it. And in ’95/’96 the IRA was beaten militarily, on their terms.

So the Good Friday Agreement, in ’98, that wasn’t the grand solution? ‘Tony Blair was wrong from the beginning. To start with, he decided he was going to be negotiating, totally the wrong thing to do! If you’re in any form of negotiation which is dangerous, you do not put the decision maker at the table because then they get forced to make a decision. (Gerry) Adams and (Martin) McGuinness on the other hand turned up and said, well of course we’re not the IRA but we represent the IRA. Then they said, well if we don’t get this then the boys will probably go back to war. Again, Blair should have said, ‘Well fuck off back to war, we’ll do you again.’ But he always conceded the point and in the end we had this upside down agreement where the losers apparently won. The IRA got everything they wanted, that they’d been fighting for for 30 years and lost. More than that, by his actions Blair blew up moderate politics which was still embryonic in Northern Ireland. It answers the question, why has nothing progressed in Northern Ireland. It’s the same today as it was the day before.’

‘Then,’ says Simm, ‘Blair put the Human Rights Act on the statute and gave them another weapon. Sinn Fein is the IRA. The IRA in Burton suits! And these endless legacy cases are just their way of continuing the fight. It’s lawfare. The Legal industrial complex, I call it.’

More and more legal cases are being brought against the SAS operations in Ireland decades ago – and it’s not just Ireland, one inquiry after another into Iraq and Afghanistan with Special Forces repeatedly interviewed. The British government, under both parties, has allowed and even encouraged murder investigations against men like George who chose to risk their lives to protect this nation. Whitehall predicts more murder charges and has stated that the Human Rights Act prevents them from drawing a line in the sand and closing investigations down.

I can’t imagine that any decent British man or woman, considering the situation in good faith wouldn’t conclude that we urgently need to bring the lawfare to an end, to enact primary legislation to stop the whole thing in it’s tracks.

Perhaps Starmer and Hermer are so befuddled by law-think that they can’t see what’s happening to the country they claim to love

Even Blair’s lot seem to understand now what a disaster the ECHR is for us, I say to George. Even Jack Straw has indicated that he thinks we have to ‘decouple’ from the convention. Are there others who secretly agree with you?

Simm says: ‘When I met Cherie Blair and I said to her I can’t believe for a moment that when your husband put the 1998 Human Rights Act on the statute he envisaged this would be the outcome and she said, no thought, ‘Absolutely not.’ So, I was thinking she is either prepared or it’s true and actually what’s happened is it’s a series of unfortunate events that they haven’t been able to control. They’ve started something and it’s just got completely out of hand; that’s actually what I think. But it means the bad guys, the IRA can flip the narrative and paint us as the murdering ones.’

In an excellent podcast with soldier turned film-maker Tom Petch, Richard Williams addressed a recent ruling of the Northern Ireland Coroner, that soldiers didn’t do enough to prevent the taking of human life. ‘What it implies is that all of us involved are simply in the SAS to kill people,’ he said. ‘We are not. The death of the terrorist is as a result of the terrorist’s actions. Would that coroner have preferred it if instead of four IRA dead there’d been four dead SAS?’

There’s another Remembrance Day question for Lord Hermer, though I dread to think what his answer would be.

George has been talking for a few hours now, telling astonishing stories there’s no space to relate: about how the SAS out-manoeuvred the most brutal gangsters in the world: the drug cartels in Colombia, the Serbs, terrorists worldwide. He’s proud of what his comrades achieved, and the incalculable human suffering they’ve prevented over the years. It should make everyone proud. But there’s one question that eats away at me like acid.

Simm still believes in this country: ‘I think it’s there, I think it’s there. I have this belief, I see it, I see it’

Perhaps Starmer and Hermer are so befuddled by law-think that they can’t see what’s happening to the country they claim to love, but how can any, any serving officer stand by and not speak out? In the last few years, SAS soldiers deployed on classified missions have been arrested, quite literally, on the airstrip as they return, questioned by the police and arrested for murder. There is even talk in Whitehall of pursuing the last few survivors of operations in Malaya, now in their nineties and this crazed situation is now measurably affecting national security. Peter Wall and Nick Parker, and the other generals who signed the letter yesterday, revealed that an exodus from the Special Forces has started. Why don’t more top brass step up to save their own men?

‘Think about it, come on Mary!’ says Simm. ‘We’ve got two senior officers out of the many we petitioned, Rupert Smith and General Peter Wall, two exceptional senior officers, have weighed in, nobody else. Why? It’s because they were complicit in the whole disaster. They think: oh I was a fool, I allowed this to happen. It’s like any MP on TV now talking about immigration. People think: hang on a sec, where were you for the last 14 years? They’d rather not say anything, thanks very much, for fear of looking a bit of a fool.’

‘And in the end,’ says Simm, ‘The good people leave. Men like Richard Williams, they’re the rock stars of the military. Once they’re past around half colonel, colonel, they go sod this, I’ve had enough, this is madness. And the people who stay are the career climbers, the do-nothings, the umbrella men and they go all the way to the top.’

The end of the line for Simm and the SAS came as a result of lawfare too. Simm chose to speak out to protect a young colleague who’d helped end the Bosnian war. ‘This young fella and me, we’re the ones who brought the Serbs in, negotiated with the Serbs, mediated with the Serbs to end the war, and then they came for us, the security services, the whole lot. It was an extraordinary set of affairs. I fought them for two years,’ says Simm, ‘and I won and at the end of it. In the end they backtracked and said, ‘Look, it’s all been a bit of a mistake.’ I said, yes, hasn’t it? They’ve got what’s called The Plot, which is jobs they can offer around the world. They said pick whatever you want. I said no. I’ve already left. My love affair is over, done. It’s the end of the affair, it’s finished. I said: you don’t need me anymore and I got up and walked out and that was the end of my career. Sad, eh?’ says Simm. It’s the first time in over two hours that he doesn’t radiate certainty.

But Simm’s love affair isn’t actually over. He’s still fighting for the SAS and thank God he is. ‘So in a sense, yes, it’s not unfinished business for me,’ he says, ‘Because the system is still truly an amazing system. The army as a whole as an institution is extraordinary, it is just constantly interfered with by people who don’t understand.’

And Simm still believes in this country: ‘I think it’s there, I think it’s there. I have this belief, I see it, I see it. We’re conditioned from within a pool that’s latent within society. It’s been the same since Alfred and the Fyrd, the army from the population,’ Simm says. ‘I met the Prince of Wales once because I had to go and brief him on one of the operations and he was going on about how unusual I was, and I said: ‘It’s not like that, the country is full of people like me, it just is. I said to the Prince of Wales, well he’s the King now isn’t he? I said give me a month and I’ll bring you 50 of me. Easy!’

Simm looks cheerful again, determined and it’s hard, despite everything, not to feel the same way. Who’d bet against him? Perhaps a government of the future will have the courage not just to stop the terrible lawfare rot, but take him up on his offer. Fifty more George Simms could be the start of something new.

Comments