People always divine themselves through material goods: hence the obsession with the Aga, recently detailed by my friend Rachel Johnson in these pages. Rachel loves her Aga – well, her Agas, she has two – because it needs to be defended from bourgeois socialists who don’t have Agas: they just want them, because self-deception is the defining characteristic of the bourgeois socialist. Me, I hate mine. I used to love her because she made me feel upper middle-class, which I’m not, and now I know I’m not, and I’m glad I’m not, please take her.

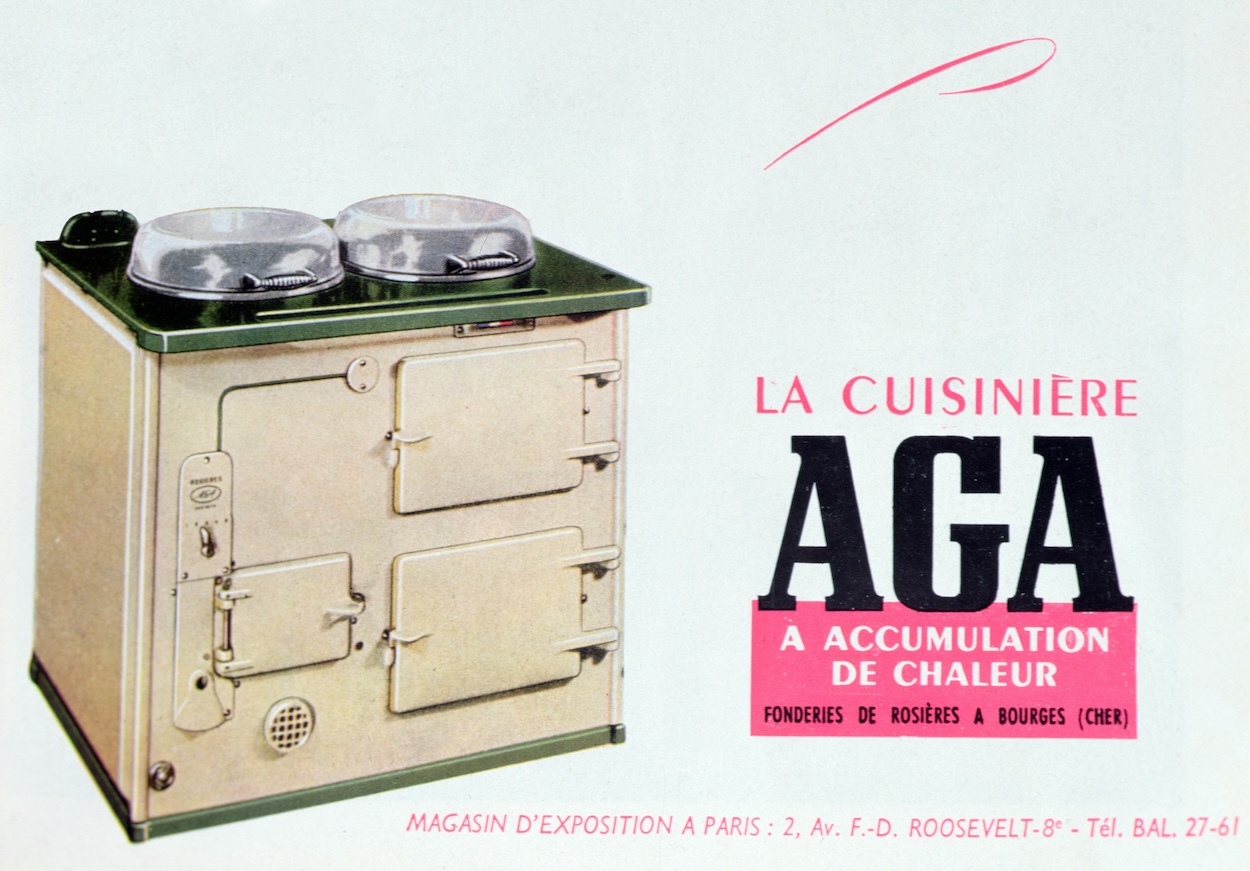

Of course, Agas are class signifiers. An Aga is like the last vestige of the country estate left after the fire sale. As in: ‘We lost the Titian but kept the Aga’. There is no Titian – there never was – but in the smoking, class-ridden ruins of this country, an Aga still means something with her solidity, her patriotism (invented in Sweden, made in Telford) and her gift for nostalgia. But there is yet still more to her than that: I wonder if the Aga is the furnace of a woman’s heart, a metal and enamel twin, which is why the husband will slide banana bread into the wife/Aga if allowed.

There is a reason women buy seven-oven Agas while hating men. The Aga is painting the study vulva pink or keeping the garden strategically untrimmed: a scream of pure, raging femininity, disguised by great marketing and bourgeois politesse. The Theory and Practice of Selling the Aga Cooker (1935) was written by David Ogilvy of Ogilvy and Mather, a genius of want-making. I read his advertising materials, and her promises, and I wanted her again. Then I punched myself in the face.

Her tasks are all feminine – cooking, heating, drying, being penetrated with cottage loaves – and, like me, she is terrible at them all. She does cook, but in her own way and her own time. She won’t be told, and if asked to cook meat will deliver a tough, turgid piece of beef, both undercooked and overcooked together. If you get wise to her – she can potentially be thwarted – and fry the meat on her hot plate, as opposed to her simmering plate, the kitchen will fill with cow-based carcinogens, and the smoke alarm will go off, because she willed it. My husband adores her. He tells us to get out of ‘his’ kitchen so he can be alone with her, like Maverick of Top Gun and his aeroplane, or the ‘three in a marriage’ lament from the late Princess Diana.

‘She heats the house,’ you say? Not true. She heats the part of the house she can touch, and in summer she heats it so well, no one can sit in the kitchen or sleep in the bedroom above. Turn her down? She behaves even worse. Oh, but she will dry your clothes. Now that is true, but, in my house, it is like drying them on a heated bin. It’s not reasonable to ask a 12-year-old boy or a 51-year-old man to wipe the Aga down so you don’t get Spaghetti Carbonara on your bedding, and even if it were, they wouldn’t do it. If guests lay the wet clothes on the hot plates – they do not understand how dangerous she is – she will set fire to the house, like Bertha Mason Rochester, the character in literature she most embodies while still being made of cast iron. The Aga is a feminist, and she is useless.

The Aga is a feminist, and she is useless

I paused between these paragraphs to make a piece of toast. Spitefully, she burnt it, and then she burnt me.

And, because she is older than I am, it is almost impossible to get her serviced because everyone who knows how to take care of her is either very old, or dead. I inherited the first heating engineer, who could still afford to live locally. Then he disappeared (died) and I fell to telephoning range shops in Truro to ask if they knew anyone who could service a Mitford-era oil-fired Aga. Eventually this brought forth Les, a tall, courtly Londoner. Les was so old he couldn’t carry the new components inside, and I had to telephone my husband to leave work to help him. Les, though, knew everything about Agas: he fiddled in the kitchen for days, face down in the tiles. Then came the bill: £1,400. It would have been more, but Les liked me. ‘I like a full-bodied woman,’ he told me, smacking his lips, because he knows enough about Agas to know they are just sex. Then Les died too.

Comments