Take my advice and steer clear of your local university. It is not just the flu that’s spreading on campus. Last month, an outbreak of trigger warnings occurred at the University of Essex. Up they popped, warning literature students about ‘violence, slavery, racism, and suicide’ in Hamlet, A Clockwork Orange and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Those infected showed signs of ignorance and hysteria.

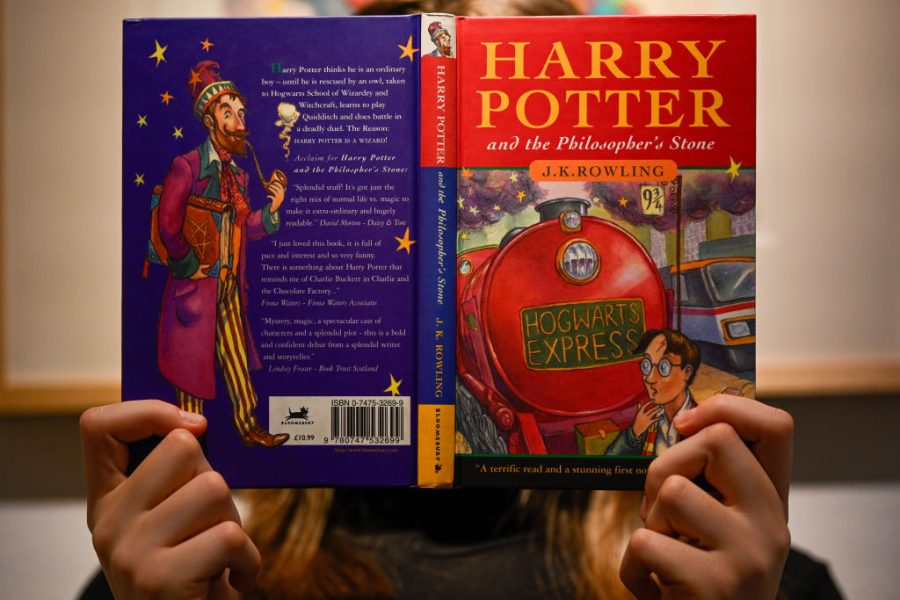

Now the plague has spread to Glasgow. Students at this ancient university are being warned that Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first in J. K. Rowling’s series about the boy wizard, contains ‘outdated attitudes, abuse and language’. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, The Treasure Seekers by Edith Nesbit and First Term at Malory Towers, Enid Blyton’s 1946 girls’ boarding school romp, are also flagged up as likely to cause offence.

Surely what’s offensive here is the fact that students – young adults – are being asked to read children’s books. They are being charged £9,250-a-year to study literature they should, by rights, have been done with by the end of primary school.

This tells us everything we need to know about declining educational standards

Don’t get me wrong. These are great books. Lewis Carroll and Edith Nesbit are tremendous authors and every child should be introduced to their beautiful prose. Countless children, in countries across the world, have become hooked on reading thanks to Rowling or Blyton and their popular page-turners. And the question of what makes a classic children’s book, or even a commercial hit, is an interesting topic for dinner party debate. But for Glasgow’s undergraduates, studying the course ‘British Children’s Literature’ presumably in lieu of a module on Milton, Swift, Thackeray or Woolf, is dumbing down dressed up as ‘textual analysis’.

To add insult to injury, however, Glasgow’s literature students are not only being expected to read children’s books, they are also being warned about their contents. This is despite the fact that generations of children have grown up unscathed, had their imagination stimulated and their vocabulary extended by entering worlds created by authors like Carroll and Nesbit. The idea that today’s young adults cannot cope with books commonly read by children in previous decades tells us everything we need to know about declining educational standards.

Blyton is a perennial target for bans and trigger warnings and Rowling comes under fire – not for anything Harry Potter says or does, but for her defence of women’s sex-based rights. We certainly might find ‘outdated attitudes, abuse and language’ in these books, especially if we extend the definition of ‘abuse’ to cover girls being punished for midnight feasts and pranking the French mistress, or Harry’s unconventional bedroom in the cupboard under the stairs. But are today’s students really so sensitive they swoon at such stories?

A spokeswoman for the University of Glasgow gives the game away. ‘Content advisories’, she said, ‘help students prepare for critical discussion.’ (Laughably, even the phrase ‘trigger warning’ is outlawed in case it evokes upsetting thoughts about guns.) ‘Unlike children reading for pleasure,’ she continued, ‘undergraduates analyse these texts in depth, which can highlight outdated attitudes around childhood, race or gender.’

So we see that, as always, trigger warnings are political. The word ‘outdated’ is revealing. Students are being told in advance not to enjoy these books (even if they are for kiddies!) but to condemn them. They must not get lost in Wonderland or Hogwarts but remain ever-vigilant for sexist, racist or classist attitudes and assumptions. But if the aim is in-depth analysis, the lecturers issuing such warnings are telling students the conclusion before they have undertaken any research. Students know the answer is ‘racism’ before they ever get to the essay question. Having been tipped off about ‘outdated’ content, they have only one job and that is to sneer.

It is all too easy to laugh at the current outbreak of trigger warnings. But their existence is desperately sad. A generation of adults has failed to inspire in children a love of reading. Youngsters who persevere regardless and make it onto a literature degree are palmed off with children’s books. But here’s the killer: read Nesbit or Blyton as a child and you enter a world of imagination and pleasure. Read them as adults, knowing your task is to muster condemnation, and you are left with nothing other than cynicism.

At Glasgow, it is not students but lecturers who need to grow up. They should expect undergraduates to read the classics and trust them enough to draw their own conclusions.

Comments