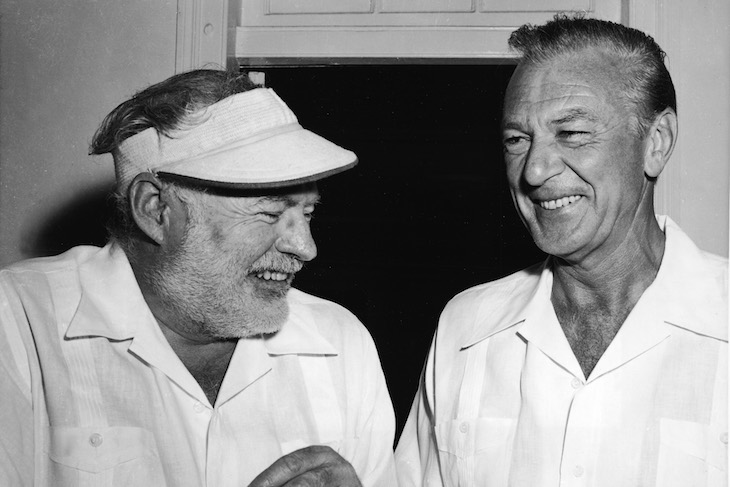

Reading is the best antidote to debauchery I know of, and I’ve been hitting the books lately. History mostly. Once upon a time I used to read novels. Back then I found real magic embedded in the prose of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Maugham, Leo T and Fyodor D, Waugh, Greene, and John O’Hara’s potboilers about upper-class swells. I was friendly with Irwin Shaw and James Jones, of The Young Lions and From Here To Eternity fame and read both men assiduously. Shaw and Jones were tough guys, army vets, and Hemingway types. Yet it was Fitzgerald, whose indelible stamp of grace, haunted my youth. Dick Diver and Tender Is The Night and the Riviera and all that. His romantic imagination transfigured his characters and settings to people and places I knew well. When I wasn’t chasing some girl or hitting a tennis ball, I was curled up reading Papa and the tragic Scott.

In 1965 Norman Mailer’s An American Dream discombobulated me. The hero throws his wife off a terrace, killing her, and then buggers the maid. Not much tenderness on that particular night. I had already met the author, and he was a full time job; his curiosity was endless and he was an intellectually and physically demanding friend. Mailer thought fiction the highest calling there is, but ironically it was his non-fiction that procured him endless literary prizes. He fathered a technique he called a true-life novel, a work of fiction based on the lives of actual people.

I never met Papa Hemingway but this briefest of examples will show you what I mean. It is the opening lines of A Farewell To Arms: ‘In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees.’ I used this passage to illustrate perfection nearly 30 years ago in these pages, and an Eton beak wrote it was the worst writing ever. I challenged him to a fight, but he was pulling my leg and we had a drink instead. Hem’s description when only 19 of a prostitute walking her beat under a dim streetlight was shattering in its sadness, and it was done by simple description of time and place. His was a great talent, pure and simple.

Fiction supposedly represented an escape, however fleeting, from the grimness and despair of many peoples’ lives. Yet the novel had been in crisis and dismissed since Charlotte Brontë’s rejection of Jane Austen, not to mention Le Figaro’s dismissal of Flaubert. Never mind. The novel died when craftsmanship, as well as hard and intelligent effort in which every sentence ‘is unostentatiously lapidary’ ceased, and was replaced by the stream of consciousness modernist bullshit practiced by the talentless solipsists of recent times.

Nothing, however, had prepared me for what I read in a New Yorker article last week. The New Yorker was and continues to be a well written weekly, one that has always published extremely boring, much too lengthy articles about subjects no one cares about except the person writing them. Since becoming a stable-mate of Vogue and Vanity Fair, however, the magazine has bent over backwards to be trendy where race, sex and religion are concerned. White males, Christians and heterosexuals need not apply. The piece that caught my eye was by one Ariel Levy about the female Jewish-Iranian writer Ottessa Moshfegh, whose novel Eileen won the Pen/Hemingway Award and was a finalist for the Man Booker. The female heroine is an ugly and disgusting person, self-pitying, resentful and angry. She snubs a rape victim because she herself has never been raped.

Levy quotes Moshfegh talking to her man friend, inducing a bum-clenching, toe-curling reaction from yours truly: ‘What are you thinking?’ ‘I am thinking what a genius you are, your writing is genius.’ Here’s some of that genius, a long passage of Eileen’s greatest joy, described as a case of explosive diarrhoea: ‘With the laxatives, my movements were torrential, oceanic, as though all of my insides had melted and were now gushing out, a sludge that stank distinctly of chemicals and which, when it was all out, I half expected to breach the rim of the toilet bowl. In those cases I stood up to flush, dizzy and sweaty and cold, then lay down while the world seemed to revolve around me. Those were good times.’

One could also call it bowel porn. But don’t despair, dear readers, yes, we are falling back to barbarism, but Ariel Levy has an excuse: she’s a frustrated proctologist posing as a writer for the New Yorker while dreaming of non-stop colonoscopies. She describes Ottessa Moshfegh: ‘Arguably the most rapidly expanding powerful voice in American letters and when she speaks of what she believes in, has spent her life working to perfect, a righteous transgressive sensitive force speaks through her which is divinity in rebellion.’

Ah yes, how wonderful our rebellion days were, when we recited Fitzgerald’s farewell sonnets to university life, ‘The last light fades and drifts across the land, the long, low land, the sunny land of spires…’ I think back and can see Natasha and Prince Andre waltzing in the winter palace, Brett and Jake downing whiskeys and listening to a Paso Doble in Pamplona, Tommy holding Nicole back while Dick blesses the beach at Antibes never to return. And Ariel Levy inhaling deeply while Ottessa Moshfegh takes a shit.

Comments