The first thing Gary Kemp bought when Spandau Ballet started making money was a chair. He’s very proud of that chair. He talks about his chair in tones midway between one of Monty Python’s four Yorkshiremen and Nicholas Serota. ‘I wasn’t making any money until “True” was successful, in 1983,’ he says. ‘The first thing I really bought was a William Morris chair. What the fuck is a 22-year-old boy living in a council house with his mum and dad doing going out and buying a William Morris chair?’

It was the first chair anyone in the Kemp family had ever owned outright, he says. ‘Everything in our house was on HP, apart from the cat. It’s very different to the old Alan Clark thing. We were handed down no furniture. Once you’d paid off the HP, you’d sell it and get something else on HP. Still have that chair. It represents a kind of hunger for things. I love the Pre-Raphaelite [and the] arts and crafts movements. For me, they were another gang of rude boys taking over the London scene.’

Like the Pre-Raphaelites, Kemp is currently experiencing something of a renaissance. Spandau Ballet have started playing shows again in their ongoing reunion, albeit with a new singer in place of Tony Hadley, who appears to have left in an enormous sulk. Kemp is onstage over Christmas and the New Year — and not in panto. He’s in Party Time and Celebration at the Harold Pinter Theatre, alongside John Simm and Celia Imrie, in the Pinter at the Pinter season. Oddest of all, he’s spent a chunk of this year playing guitar and singing with Nick Mason of Pink Floyd, in the band Saucerful of Secrets, performing the music Pink Floyd recorded between 1967 and 1972. I can’t vouch for the Pinter, but both the new-look Spandau Ballet and the journey back to the hippie heyday are tremendous fun.

You don’t need to be much of an amateur psychologist to work out that Kemp is fairly obsessed with class. It comes into his discussions of everything. In one brief monologue, he sums up the way class affects all three of his current projects. ‘I found myself in pop music because I’m working class. The arts are very divided on class lines. Theatre is a real last bastion of class. For all its left-wing politics and ethics, it’s obsessed with the class system.

‘If you’re a working-class actor, you will find it so much harder to achieve anything in serious theatre and in movies. Even if you change your accent, it’s still there, and it’s recognised by casting directors, mostly. In music, if you’re working class it’s: “Get yourself involved with pop music.” That’s where prog rock came from — it gave the middle classes a reason to find themselves in this successful business. “What if we make electric music that sounds a bit like Bach and is a bit worthy, and we give it deep stories and make it full of meaning. Can we do it then? Oh yes, of course we can!”’

But how could he not have been shaped by class? He was a poor kid who went to a grammar school, where he discovered there were people who were not like him. People with books on their shelves and woks in the kitchen. But he could see something to aspire to. Though education wasn’t valued by his parents, he became a reader, and he worked out he was artistic. He took himself off to an Anna Scher theatre club, paying with his paper-round money, and was in short order cast in Children’s Film Foundation films. When he got his first role, he hadn’t even told his mum he was going to theatre club. He had to go home and tell her he was going to be on telly when she didn’t know that he’d been acting.

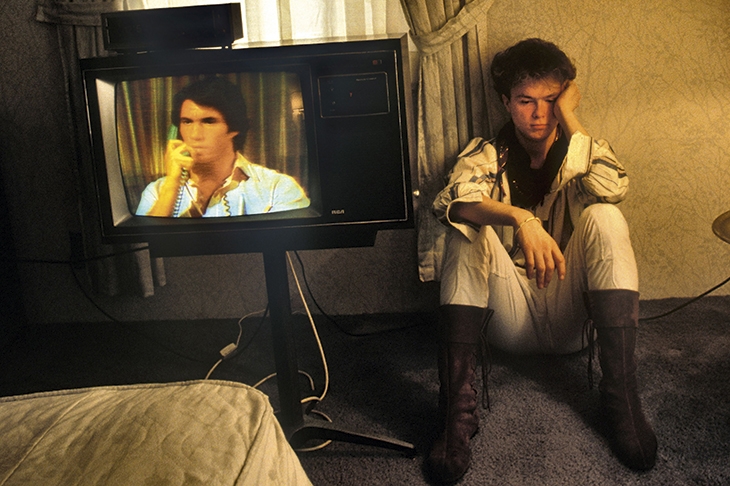

His dad bought him his first guitar one Christmas, from a shop on the Holloway Road (‘At first I was disappointed, because it wasn’t a toy’), and soon he was writing songs. By his mid-teens he was on TV playing them — there’s a clip on YouTube of him playing a suitably florid teenage composition on the ITV children’s show You Must Be Joking! with his young bandmates, the actors Phil Daniels and Peter-Hugo Daly. From there, it was a flit around musical styles until he found an identity among the new romantics and formed Spandau Ballet.

Spandau Ballet became proper pop stars with ‘True’, a song so redolent of summer 1983 that it ought to come with a free chrome-and-black leather armchair and a pair of shoulder pads. You still hear it today — on any minicab journey after midnight, there’s a one in three chance it will come on the radio. And, Kemp notes, ‘so many people have told me it’s their song, from taxi drivers to Kevin Costner. I’ve done something that’s done some cultural damage. That makes me happy.’

The irony is that, like almost all pop stars, Kemp was the last person who should have been writing a love song. The nature of the band is to be a gang — Spandau, mates from the same streets in north London, were definitely a gang — and to be a gang precludes meaningful romantic relationships with women. ‘There was never going to be anything between me and a fan, or someone I met on the road,’ Kemp says. ‘It would have to involve at least two nights of dinner and going to a gallery. I was too nervous, too inhibited, too shy. I was a really late starter. “True” came out of courtly love [for Clare Grogan, of the group Altered Images], which I found much more moving, like those old poets who would write about someone without ever wanting to consummate it.’

But then once the gang members actually start to meet women for more than a night at a time, they stop being a gang. And once they stop being a gang, it’s hard to carry on being a group. ‘And that did happen. As we got towards the end of the 1980s, the end of our tenure, there was a sense of relationships outside the group starting to infiltrate the band. But a band relies on this hierarchical chemistry. It’s like everyone gets separate managers.’ And for Kemp — who, despite resenting the fact that no one else in the group wrote songs, was also so controlling he wouldn’t have let them — the collapsing of the hierarchy was no good at all. And so Spandau came to their first ending, in 1990, and Kemp was never really a pop star again.

It’s perhaps a good job he had that decade that made him, though. Without that, he’d have had to get a proper job, and his last proper job didn’t go all that well. While Spandau were waiting to be signed, he worked at the Financial Times as a prices clerk. One of his jobs was to give the dollar-pound exchange rates to the typesetters to put into the next day’s paper. He managed to get it wrong. He was summoned to see the editor, Freddy Fisher, where he was told: ‘Don’t you dare ever mention this to anyone.’

Too late.

Comments