The Spectator’s legal action in the Alex Salmond affair has prompted the Holyrood inquiry to rethink its approach. The magazine went to court to argue the media’s right to publish and the public’s right to read evidence from Salmond which the inquiry is refusing to publish.

A redacted version has already appeared on The Spectator website. Lady Dorrian agreed yesterday to amend an order against reporting information relating to the criminal trial against Salmond, which cleared him of 13 charges of sexual assault. The Sturgeon government’s separate sexual harassment probe into the former First Minister has previously been ruled ‘unlawful’ and ‘tainted by apparent bias’ by a Scottish court.

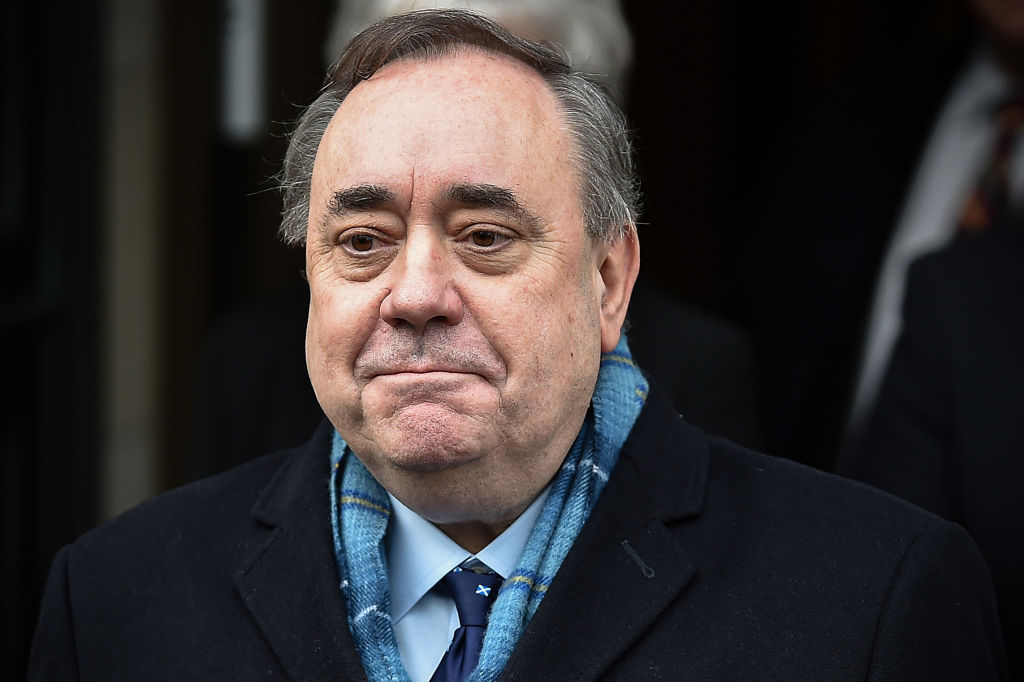

Salmond is a first-class showman and he has the rhetorical skills to embarrass the committee

Now the inquiry has postponed a scheduled appearance by Nicola Sturgeon on Tuesday to answer questions on what she knew and when she knew it. The decision was taken at an emergency meeting of the committee this afternoon. It was followed by a statement saying the inquiry ‘must have the time to reflect on the impact on its work once the full written judgment is published early next week’.

Salmond announced earlier in the week that he would not appear before the inquiry after it refused to publish written evidence that he provided. Doing so, it is argued, would prevent Salmond referring to certain matters in his oral testimony. His solicitor protested that ‘asking a witness to accept the constraints of speaking only to evidence selected by you on the undisclosed advice and direction of unidentified others is not acceptable in any forum’. Today’s statement also repeats the inquiry’s determination that it should be Sturgeon, not Salmond, who gets the last word:

‘It is important for the committee to hear from Mr Salmond and the committee has always been clear that the First Minister should be the last witness to appear before the inquiry.’

The Spectator seems to have forced a reconsideration that might see Salmond turn up to the committee after all, but it’s by no means certain. The committee can try to compel him to appear, but if it does so without budging on the publication of his written evidence, it risks a counterproductive spectacle.

Salmond is a first-class showman and he has the rhetorical skills to embarrass the committee while remaining within the law. The general public knows neither the law nor the procedures of parliamentary inquiries and it would not be difficult for him to frame the proceedings as Kafka-esque. Ultimately, the inquiry must decide whether compelling Salmond under these circumstances would only win him public sympathy and undermine their own work.

Whatever happens, it remains the case that few people in Scotland outside of political, legal and media circles understand, or are even following, this case. It is too byzantine and what information is in the public domain is near-impossible to make sense of without the information that is not. It is a hydra-headed scandal implicating government, civil and criminal proceedings, parliamentary oversight and internal SNP politics. But it may as well be a twice-expensed bus ticket for all the cut-through it is enjoying with the punters.

What Salmond’s supporters are suggesting — that he has been the victim of a politically-motivated conspiracy orchestrated by the government he once led — may be ludicrous, it may be true, or it may be some messy midpoint between the two. No matter what the inquiry does, it is unlikely we will ever get to the truth.