The timing for Germany’s school-leaving exams couldn’t have been worse this year. Typically, the exams including the Abitur – equivalent of A-levels – take place between March and June to give school leavers enough time to apply for apprenticeships or a place at university as the winter term starts in October. This year, however, the outbreak of the corona pandemic caused schools across Germany to close, casting doubt on whether final exams could take place.

In Germany, the 16 federal states are in charge of education policy which usually creates a mosaic of regulations, exceptions and exam schedules. In March, the state of Hesse, home to the financial metropolis Frankfurt, had already begun holding exams, while other states were still in favour of cancelling the Abitur as well as other school-leaving exams. The northern state of Schleswig-Holstein suggested awarding an ‘average grade’ based on coursework and other exams taken over the last two years. The state’s education minister, Karin Prien, came under political fire for her proposal and was forced to backpedal after a few days. ‘Playing a lone hand in such an important matter is unreasonable,’ said her colleague Ties Rabe, the education secretary of Hamburg.

‘I didn’t go to school for twelve years to then somehow slide out because of corona’

In the end, the 16 states showed unusual unity and agreed in late March that exams should take place as planned. The decision was met with protests from students, pleading health concerns and revision difficulties. But the protests were small in numbers and mostly got lost in the general chaos of the crisis. The claim that the exams under these extraordinary conditions would put psychological pressure on students did not budge the state governments, especially because student representatives were in favour of the plan that was outlined. ‘It wouldn’t have felt like graduation if we hadn’t taken the exams,’ said Joshua Grasmüller, the elected student representative in Bavaria. ‘I didn’t go to school for twelve years to then somehow slide out because of corona.’

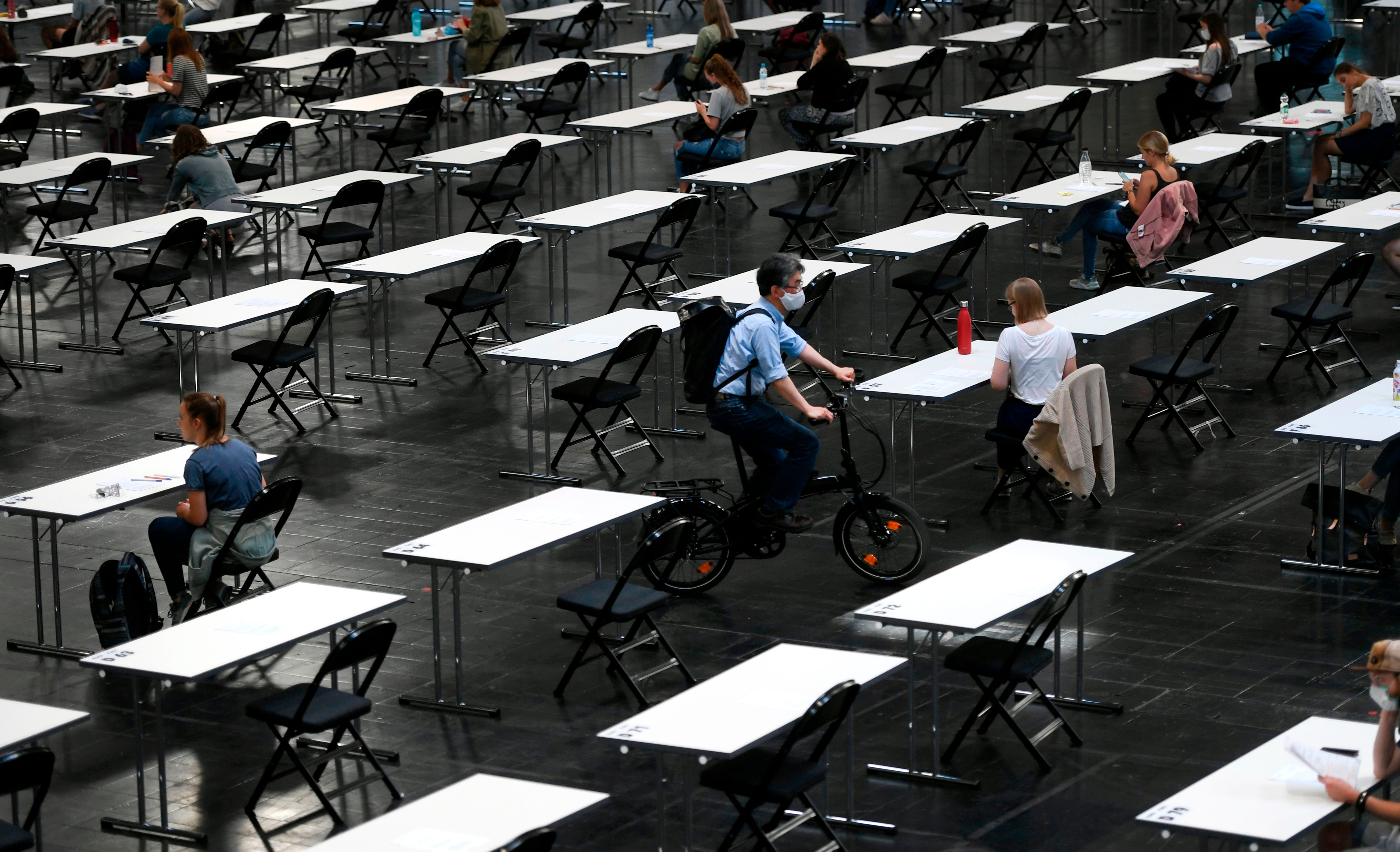

Schools were largely concerned with challenges related to physical distancing and the use of personnel inside their facilities. Exams were mostly held in well-aired classrooms rather than big halls, with smaller numbers of students sitting at least 1.5 metres apart. In most states, teachers who belong to vulnerable and high-risk groups were exempt from attending the exams.

However, Schleswig-Holstein’s education minister Prien came under fire once again because she, just like her colleagues in Saarland and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, demanded more than just a single doctor’s note from teachers to allow them to be absent from the classrooms. Teachers in Schleswig-Holstein had to go through a thorough examination by occupational physicians and could be forced to go to school despite voicing concerns related to their age or health history.

Prien, who was called ‘the most cold-hearted education minister of Germany’ by the tabloid Bild, seemed fed up with the fact that 2,000 out of 28,000 teachers in her small state had filed requests to stay home.

This controversy, however, was just a brief and somewhat forgettable episode in an otherwise smoothly run operation by schools and ministries. Before the exams, Bernhard Kempen, the chairman of the German Association of Higher Education, had suggested lowering entry requirements for university subjects such as law and psychology if the results would be worse than in other years. But these concerns turned out to be unjustified, as several states reported results that were marginally higher than usual. In Berlin, for instance, the recorded Abitur average was 2.27 on a scale from 1 to 4 and thus higher than in the previous nine years. Moreover, 96.7 per cent of the students in the capital passed the exams compared to 95.4 in per cent in 2019, while 2.5 per cent achieved the highest possible average compared to 2.1 per cent in 2019.

Education experts speculated that the improved results had less to do with an alleged ‘corona bonus’ granted by examiners and more with the fact that Germany’s restrictions during the peak of the pandemic caused fewer distractions for students. Most of those who passed the Abitur will enrol at university in a couple of weeks, never having dealt with the kind of uncertainty that British students have experienced. For all the protests, it is Germany’s students who have come out on top.

Comments