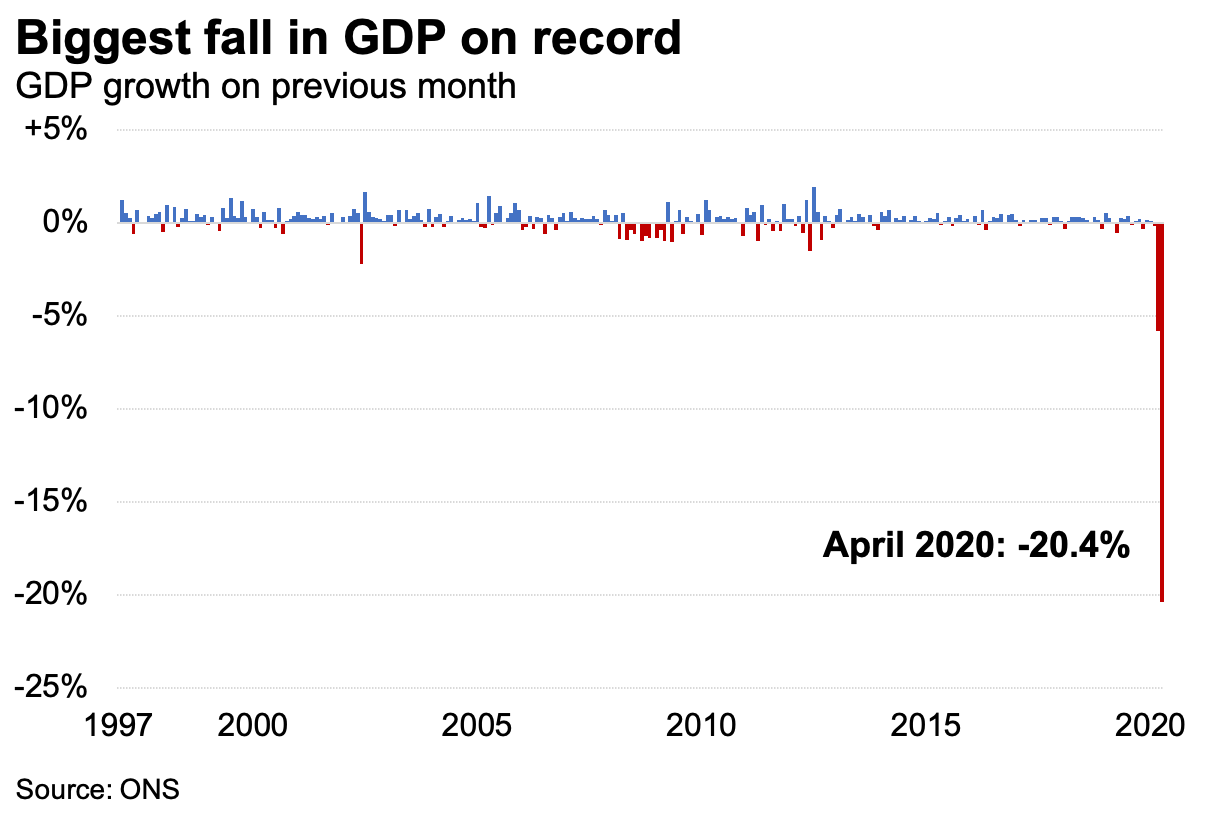

Putting the UK into lockdown was only going to send growth in one direction: down. While today’s figures from the Office for National Statistics were expected, they nevertheless confirm that the UK has experienced its largest monthly economic contraction on record.

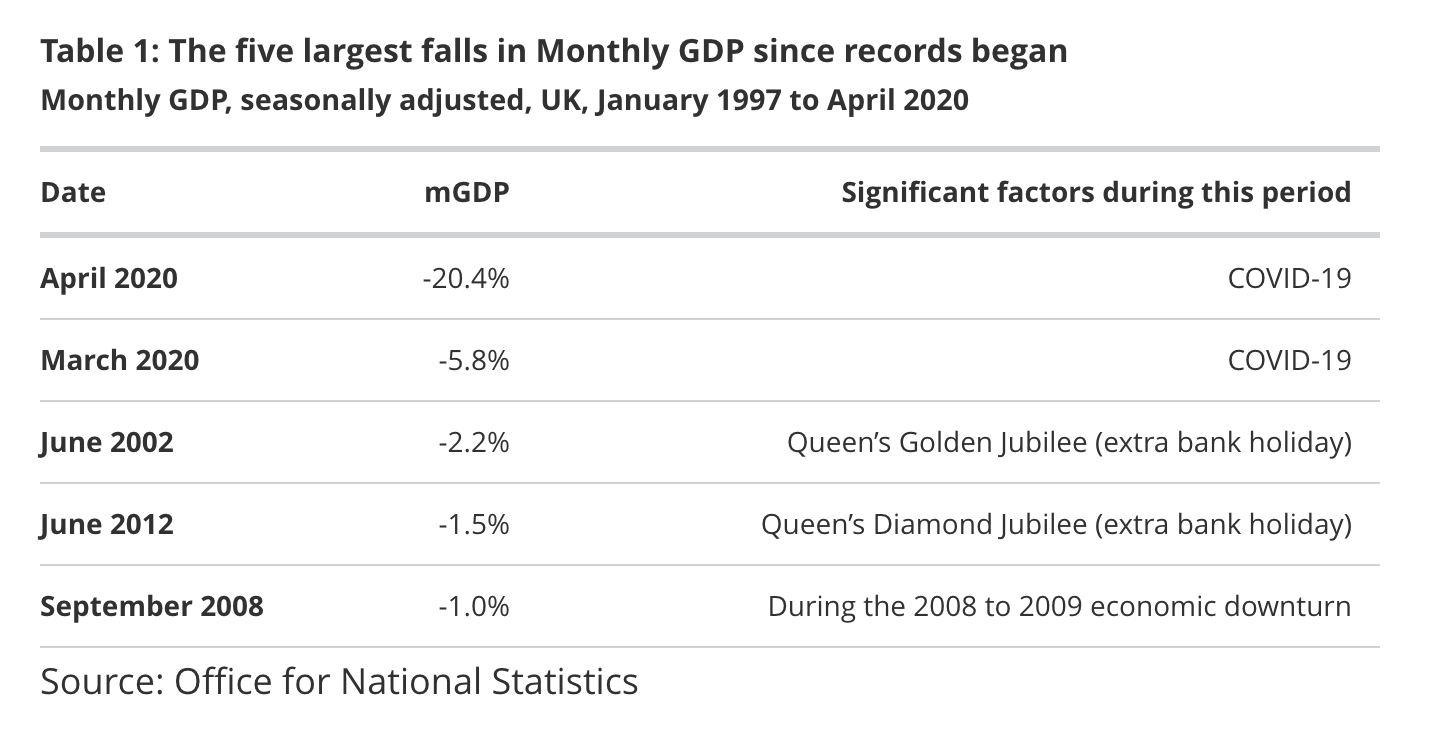

The UK economy shrank 20.4 per cent in April. Combined with March’s GDP drop (now the second largest fall since records began), the British economy is a quarter smaller than it was in February. Putting these figures alongside other monthly slumps makes for stark comparison. Hits taken for additional bank holidays and for the pain experienced during the financial crash barely compare to what’s happened in light of the shutdown of Britain’s economy.

The make-or-break for a fast recovery could come down to decisions and timings over the next few weeks.

The figures covering March and April include five weeks of lockdown, which has continued for nearly 12 weeks now, though the figures reflect when lockdown rules were most strict. Still, the government has been notably slow to ease the lockdown measures, trailing Europe and the United States for reopening the economy. This raises questions about what May’s figures will look like, and whether the V-shaped recovery seen in scenarios from the OBR and Bank of England can actually take place.

The make-or-break for a fast recovery could come down to decisions and timings over the next few weeks: if most businesses can reopen in summer months, and confidence grows that the UK can handle a second wave of the virus more efficiently than the first, growth could spike dramatically.

But if business is slow to pick up and customers doddle in their return to the shops, the UK is likely to be looking at a dragged-out, U-shaped recovery. If hospitality and leisure sectors can’t have a summer season all together (or it is ruined by the two-metre social distancing rule), and fears of a second wave put off customers all together, the UK could have a very serious, L-shaped economic fiasco on its hands – that is, stagnant growth and chronic unemployment.

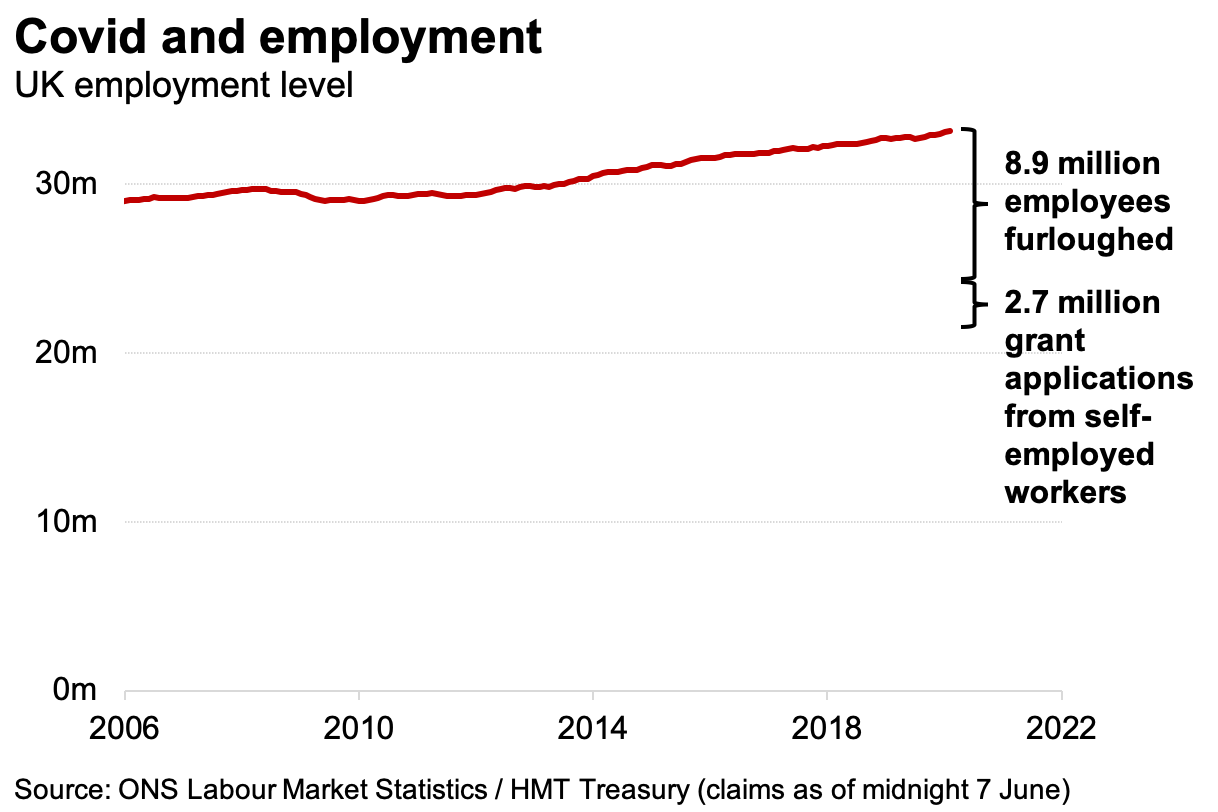

Nearly nine million employees are currently furloughed and almost an additional three million self-employed workers have applied for support grants. If the economy doesn’t turn upwards fast, those jobs remain in serious jeopardy. And as Ross Clark explains on Coffee House, today’s dire figures may still be too optimistic. The ONS struggled to calculate April’s figures, as many businesses have totally closed up shop. In other words, ‘it has put these monthly GDP figures together courtesy of those businesses which did still have someone answering calls, emails and so on,’ perhaps overlooking those in the more financially difficult situations.

There has never been much dispute over how severe the economic downturn would be. Completely shutting down nearly every sector of the economy was guaranteed to result in such a fall. The question that remains is how quickly the British economy can turn around: the hope remains for a V-shaped recovery, but accounting for the pace of the UK’s exit from lockdown, the real figures may prove far more sluggish.

Comments