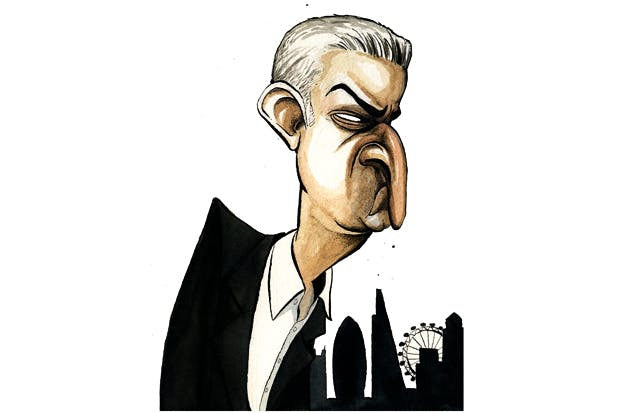

It is often said a job is what you make of it. If so, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that London’s mayor Sadiq Khan regards his mainly as a means of burnishing his personal brand. Rather than getting to grips with the core responsibilities of his position – making transport work better, getting more homes built and fighting crime – his mayoralty has been punctuated by an apparently endless series of photo opportunities and overseas tours, often related to issues over which he has no direct responsibility.

Today he took an entourage to Brussels to discuss his post-Brexit agenda with big players at the European parliament and European commission, fighting, as he put it himself, “for a deal that protects London’s economy and the rights of all Londoners”. Khan was in Belgium, we were told, to try and ensure Londoners left “heartbroken” by Brexit could retain their EU citizenship rights. ‘The mayor is deeply concerned that millions of Londoners and other British nationals, who never wanted Brexit, have lost the rights they enjoyed as EU citizens,’ according to City Hall.

Khan, obviously, has no remit to decide on any aspect of the UK’s future relationship with the EU, from citizenship rights to financial markets. EU officials, including chief negotiator Michel Barnier must have known this: that Khan was raising issues he could not deliver on and thus engaging in what is traditionally known as “gesture politics”. Yet Barnier and Guy Verhofstadt, the EU parliament’s former Brexit negotiator’, were more than happy to be pictured alongside him, no doubt delighted at the opportunity to stoke the impression of dissent on the British side.

Posturing as leader of a pretend city state rather than engaging in the grind of driving improvements to key public services in the UK capital seems much more suited to Khan’s skill set. A flair for self-promotion has so far kept him as the overwhelming odds-on bookies’ favourite to retain the mayoralty in May. Yet even the most cursory look at his record would suggest he does not merit a second term.

On his watch Crossrail, the key London public transport scheme of the era, has turned into a debacle. It was supposed to open in December 2018 but is now not expected to do so until 2021 at the earliest. What’s more, it is on course to cost at least £2bn more than its initial £14.8bn budget.

On house-building, his record is scarcely any better, with new affordable home starts currently running well below the numbers he pledged to deliver.

On crime, the record is even worse, with a terrible run of violent crime and a leap in the number of London homicides to a ten-year high. Many of the killings have involved knives, a predictable consequence of the political clamour to reduce the use of stop and search, which Khan himself was at the forefront of.

Having made driving down the use of stop and search a key part of his campaign to get elected mayor in 2016, the former human rights lawyer was forced to change tack half way through his term and began talking up the technique – when used in conjunction with improved intelligence – as “a vital tool for police to keep our communities safe”.

More recently he has sought to depict London’s violent crime wave as a national issue and largely the fault of Tory austerity, becoming noticeably tetchy when questioned about it.

Given the left-wing and anti-Brexit composition of London, it would be quite remarkable were Khan to fail to put together a sufficient rainbow coalition to comfortably retain the keys to City Hall in May. Yet if he wishes to be the left’s answer to Boris Johnson and use the mayoralty as a springboard to his national party leadership – and ultimately a tilt at 10 Downing Street – he will need to do more than just match Johnson for photo-opportunities. He will need to deliver some noticeable successes too. Where Johnson could point to the 2012 Olympics and falling crime, Khan is left to hope that the nickname “Weak Sadiq” does not take hold in time for polling day.

Comments