Franz Kafka is one of a handful of writers whose names have become an adjective. First coined in the 1940s, the ‘Kafkaesque’ was originally used as a byword for state-sponsored terror, whether fascist or Soviet, but since then its scope has vastly expanded.

Today’s uses range from the more trivial frustrations of daily life to serious miscarriages of justice, such as the Post Office Horizon IT scandal. During his 2023 trial for ‘discrediting’ the Russian army, which resulted in a 2.5 year prison sentence, the human rights campaigner Oleg Orlov pointedly sat in the courtroom reading Kafka’s The Trial. More recently, Kafka’s novel has been evoked by the US far-right newspaper The Epoch Times in an article about Donald Trump’s hush money trial. Likening ‘Donald T.’ to Josef K., it claims that the former president ‘has been subjected to more bizarre allegations, secret investigations … and prejudiced legal proceedings than even Kafka could have imagined’.

We cannot know what Kafka would have thought about his iconic status

Kafka, who was a reticent and deeply self-critical person, would probably be horrified by the existence of the Kafkaesque – but also maybe just a little gleeful. In his novels and stories, he often plays with language, showing that words have the power to disorient and lead us astray.

A brilliant example is his 1917 short story ‘The Cares of a Family Man’, which revolves around an uncanny thing-creature called Odradek. Odradek cannot be captured, least of all by language. In the opening paragraph, the narrator tries to define the word by tracing its roots. Are they Slavonic or maybe German, he wonders, before concluding that neither of them ‘offers any help in discovering the meaning of the word’. It’s a twist which typical of Kafka, who often plays with meaning, with the act of interpretation leading his characters (and readers) down various rabbit holes. This open-endedness is also one of the reasons why his texts have remained so resonant over the past century, eliciting responses which vastly outstrip the often glib and reductive uses of the Kafkaesque.

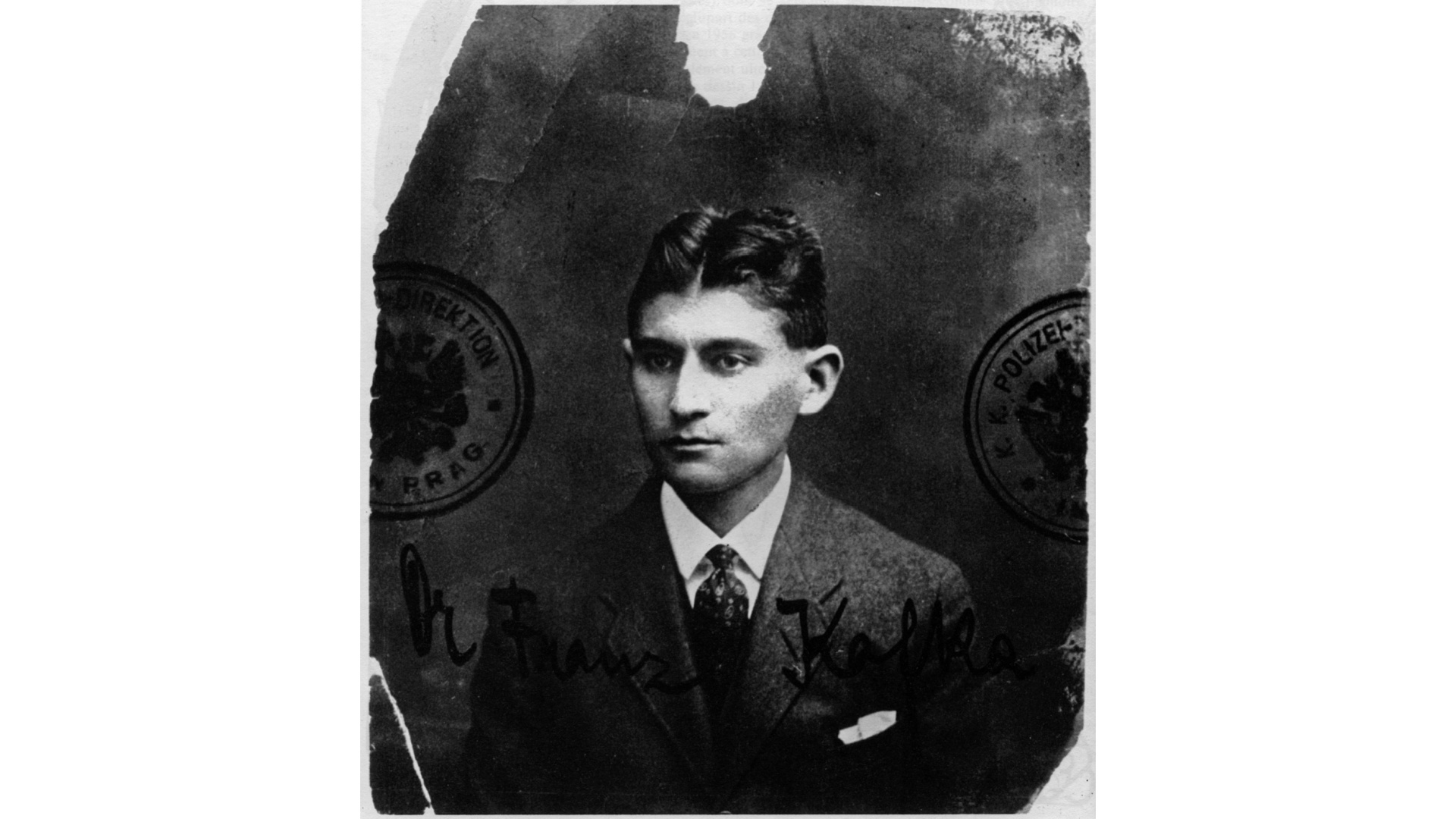

Kafka was born in Prague in 1883 as the eldest child of German-speaking Jewish parents. He worked as an insurance lawyer and mostly wrote at night. Though he got engaged three times (twice to the same woman, the Berlin office clerk Felice Bauer) he never married. Contrary to common perception, he was no solitary genius but a sociable and popular man with a large circle of friends and a wide range of passions and interests. A strict vegetarian, he also followed the daily exercise routine of a Danish fitness guru. He loved travelling, gardening and wild swimming, and was fascinated by photography and film, which have left deep traces in his writings.

He died on 3 June 1924 in a sanatorium near Vienna at the age of just forty. In the final weeks of his life, when his tuberculosis had spread to his larynx, Kafka’s doctors instructed him not to speak. He dutifully obeyed this command, using pen and paper to communicate with his partner Dora Diamant and his friend, the medical student Robert Klopstock, who were with him until the end. These so-called ‘conversation notes’ paint a vivid picture of his final weeks. They often revolve around trivial things, such as food and drink (Kafka craved a cool beer but this was out question) and the flowers Dora brought into his bedroom, but there are also glimpses of his inner state, his fear of dying: ‘Put your hand onto my brow for a moment to give me courage’.

These conversation slips are on public display for the first time at the exhibition Kafka: Making of an Icon at the Weston Library in Oxford. As its title implies, the exhibition the addresses that most thorny of questions: how did a little-known Prague author with only a handful of slim publications become one of the most resonant voices of modern literature?

Kafka’s iconic status is summed up by Andy Warhol’s painting of Kafka, part of his Ten Portraits of Jews in the Twentieth Century, which is a centrepiece of the exhibition. His portrait is accompanied by other creative responses, ranging from ‘Insect Enemies’, a newly commissioned installation by London-based artist Tessa Farmer to the script of a radio adaptations of The Castle for BBC Radio Four by playwright Ed Harris; and from Arthur Pita’s 2011 award-winning Royal Ballet production of The Metamorphosis to A Cage went in Search of Bird, a new anthology of Kafkaesque stories featuring contributions by Ali Smith, Elif Batuman and Naomi Alderman. These different responses all illustrate one central fact: Kafka’s enduring fame is the result of many voices, of readers from around the world who have made his works their own.

The centenary of Kafka’s death also requires us to return to his original writings and specifically to his manuscripts, which are at the heart of the Oxford exhibition, the largest ever mounted on Kafka. Indeed, the Bodleian Library is home to the majority of Kafka’s papers. An animation by Rebecca Harding shows how this archive ended up in the United Kingdom; it’s a story of persecution and exile, of chance, luck and extraordinary generosity.

The exhibited manuscripts range from masterpieces such Kafka’s 1912 novella The Metamorphosis and his last novel The Castle to lesser-known stories such as his late ‘A Hunger Artist’. They also include selection of his expressive drawings, which illustrate Kafka’s dual talent as a writer and a draftsman. Some of the most resonant manuscripts on display, however, are not literary but personal. They include the above-mentioned conversation slips as well as an early diary entry from 1911, in which Kafka declares: ‘Without a doubt I am now the intellectual centre of Prague’. It’s an astonishing statement for an author who, by this point, has only published a handful of short stories. Kafka then obviously got scared by his own hubris, for he crossed out this sentence until it was (almost) completely illegible. But the underlying sentiment still stands. It reflects Kafka’s deep commitment to his writing, which he was willing to pursue at the expense of his family (his father resented his literary ambitions), his relationships and his health.

But there’s another side to Kafka, the flipside of this unwavering confidence and commitment. This other side is expressed in a 1922 letter to his best friend Max Brod in which the terminally ill Kafka instructs Brod to burn all his unpublished manuscripts, diaries and letter. Brod famously, and controversially, ignored Kafka’s last wish (as he had told Kafka that he would). Instead, he immediately set about publishing these works, starting with The Trial, which appeared in 1925, just one year after Kafka’s death.

Brod’s posthumous editions made Kafka the world author he is today, for his global fame only started after his death, propelled by the tumultuous history of the 20th century, which his works seemed to anticipate. Without Brod, 95 per cent of Kafka’s work would have been lost, but his act of defiance nonetheless poses a moral dilemma, one in which we are also caught up as Kafka’s readers.

We cannot know what Kafka would have thought about his iconic status, but his writings give us a glimpse of his likely response, his deep anxiety concerning his literary legacy. Towards the end of the above-mentioned short story ‘The Cares of a Family Man’, the narrator spells out why he finds Odradek so unsettling. Not only can this thing-creature not be grasped or understood, but because he isn’t actually alive, he also cannot die. This raises an unsettling prospect for Kafka’s narrator. Odradek ‘obviously doesn’t harm anyone; but the idea that he might outlive me it almost painful to me’. Kafka’s works confront that most enduring of human questions: the prospect of our mortality and what remains of us after we die. As his writings so resonantly show, to leave a legacy is to relinquish control, to allow others to continue that story.

‘Kafka: Making of an Icon‘ is on at the Weston Library Oxford from 30 May until 27 October 2024.

Comments