LP Hartley could not have been more wrong. The past is not a foreign country to which we

can never return. It fills the minds of the living and stops us seeing the present clearly.

LP Hartley could not have been more wrong. The past is not a foreign country to which we

can never return. It fills the minds of the living and stops us seeing the present clearly.

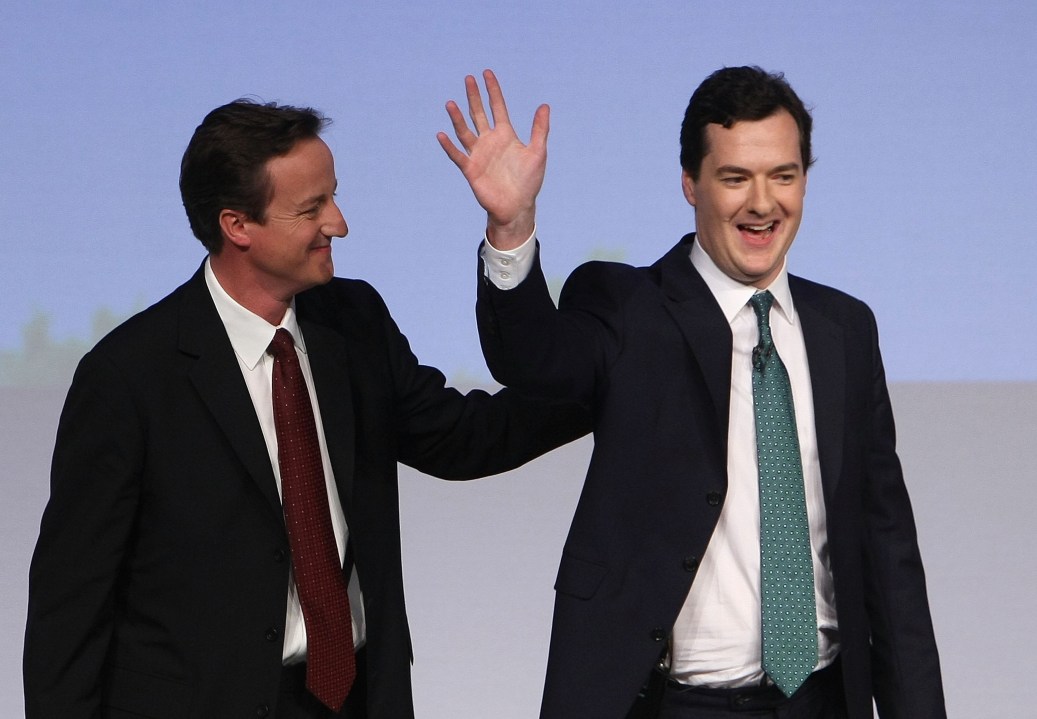

My Observer colleague Andrew Rawnsley tells our nervous readers this morning that David

Cameron and George Osborne have no Plan B for the economy. They believe they are right and will not change course, in part because the myths of the past possess them, specifically the myth of

1981.

Outraged by the destruction of industry and mass unemployment the monetarists’ tax rises and high interest rates and overvalued pound brought, 364 economists wrote to the Times attacking Mrs Thatcher’s government as an alliance of crazed ideologues pursuing policies that had “no basis in economic theory”. The Conservatives held their nerve, and within months inflation fell and interest rates and the pound fell with it. Economists came to think that inflation targeting was the first task of policy makers. The Tories went on to win three more elections.“The final reason why they do not have a Plan B flows from the way they interpret history. The prime minister and the chancellor are keen students of the Thatcher governments, especially her first term. The pivotal moment was the budget of 1981 introduced by Geoffrey Howe, then the chancellor, with Nigel Lawson, then the financial secretary, as his principal lieutenant. They imposed further deflationary measures on an economy already in recession. Mrs Thatcher made one of her most famous speeches that year, the one in which she declared ‘the lady’s not for turning’.”

As someone who saw the misery of that time, I find it very hard to accept the received wisdom. But I know that what matters in politics is what is believed not what is true, and can see why today’s Tories want to believe the story of 1981. Its appeal is almost Churchillian. Tough leaders stood alone. They ignored the panicking naysayers and the so-called “experts”. Their task was thankless. Their road was hard. But after suffering unwarranted abuse, they slogged through to the sunlit uplands where political vindication and electoral success were theirs.

The trouble is the story has no relevance to today’s crisis. Granted, the economic worries are as acute. We are not recovering from the Great Recession of 2008. The economy is at best stagnant and at worst heading back into recession. Households are facing the sharpest cut in living standards since the 1920s. As David Cameron and George Osborne summon the spirits of Margaret Thatcher and Geoffrey Howe and decide that hard times are the best times to impose tax rises and spending cuts on a weak economy, the past rushes back.

The parallels start and stop there, however, because unlike in 1981 no one can see where the growth will come from to balance austerity. Unlike Mrs Thatcher, David Cameron cannot look forward to a cut in interest rates because they are already at their lowest level since William and Mary were on the throne. He cannot hope that the pound will help exporters by falling because, surely, it cannot go much lower. He cannot say as Howe and Thatcher did that recovery will be ours when inflation is brought under control, because the Bank of England has given up on controlling inflation. He cannot hope for a consumer-led recovery because feckless British consumers are up to their neck in debt, could well see the prices of their over-valued homes fall this year and, as I mentioned, must manage with declining incomes. True, many businesses are sitting on cash, but there is a dearth of investment opportunities.

Instead of having a coherent policy for recovery, the Conservative and Liberals have only a self-pitying and self-congratulatory story from the 1980s that allows them to redefine pig-headedness as “toughness” and inertia as “bravery”.

Commentators often look at the former spads and policy wonks, who lead the three major parties, and contrast them unflatteringly with the well-rounded statesmen of the past. “They don’t read enough history,” we mutter. After the events of the past six months, I think we should drop that line of attack. In the cases of Mr Cameron and Mr Osborne it would be better if they had read less history, and best of all if they had read no history at all.

Comments