It’s an irony of Western art that our vision of modern metropolitan life was shaped, via Impressionism, by ukiyo-e prints — ‘pictures of the floating world’ of Edo, Japan.

It’s an irony of Western art that our vision of modern metropolitan life was shaped, via Impressionism, by ukiyo-e prints — ‘pictures of the floating world’ of Edo, Japan. In his new exhibition, Tokyo, at Flowers East, Jiro Osuga updates that vision for the 21st century.

The son of a Japanese businessman, Osuga left his native Tokyo for London in 1970 at the age of 12 and studied at Chelsea and the Royal College of Art. Since his first exhibition at Flowers in 2001, he has capitalised on his confused cultural identity and natural shyness, projecting a bashful, bespectacled comic persona that has come to dominate his work. In his 2009 installation ‘Café Jiro’ at Flowers Central, painted Jiros occupied all the pavement tables and all the bar stools in the café window. But perhaps because he’s back on home territory, his approach to Tokyo seems a little more detached.

On past form this oddly adventurous artist was unlikely to settle on a standard exhibition format, and with both floors of the gallery to fill he has gone for an immersive environment. Visitors are met at the gallery entrance by life-sized cut-outs of bowing Japanese greeters, the woman dressed in a traditional kimono, the man wearing a dark suit and Osugo’s face. Inside, between paintings of Tokyo streets, shops and eateries, you pass green Japanese street signs fixed to the walls and step over painted replicas of manhole covers — one is open to reveal a young Osuga looking up disconcertingly out of the drain.

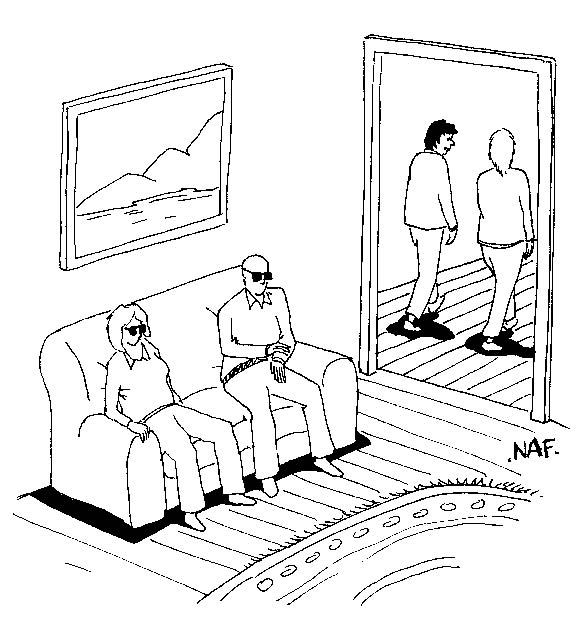

The centre of the main gallery is carpeted in an enormous aerial view of Tokyo — in a polite send-up of tea-ceremony ritual, a sign asks you to ‘PLEASE REMOVE YOUR SHOES BEFORE STEPPING ON THE PAINTING’. The side gallery has been turned into an interactive zone, with a joke souvenir stall stocked with painted knick-knacks, an oracle for visitors to consult and a wall of painted masks to try on. Some have cartoon faces but many are portraits of ‘real’ Japanese; a mirror is secreted among them to trick you into mistaking your own face for a mask.

There’s a melancholy tinge to Osuga’s humour, and it colours his paintings. His 21st-century floating world is one of parallel lives and Lowryesque loneliness: there’s no human contact between the hungry diners hunched over the counter of ‘A Beef on Rice Place’ or the wan night-time shoppers going their separate ways along ‘A Shopping Street’ intrusively bright with neon. It’s hard to explain the haunting quality of these colourful pictures, though the pathos is more obvious in the image of a young Osuga caught in a traffic mirror kicking a football along a deserted street, or the view down the empty hallway of a Tokyo flat with slippers waiting to welcome the occupants — and outdoor shoes neatly ranged on a painted mat extending out into the gallery space.

There’s no precedent for Osuga’s naïve style in Japanese art, and his artistic sources are clearly Western. The convex mirror trick recalls Van Eyck and Velázquez, the souvenirs and masks carry echoes of Ensor and the communal bathhouse in ‘Washing’ prompts a topical comparison with Gossaert. But the attention to detail is, I suspect, Japanese. The planning of the show’s installation is a tour-de-force, culminating in a near life-sized view of a train pulling into a Tokyo Metro station, seen from the upstairs gallery balcony as if from the opposite platform. My admiration for this ingenious bit of staging doubled when a real live London Transport train rattled past the windows behind me.

Upstairs, Osuga indulges a recurrent obsession with the passage of time. Two walls are covered in his signature hinged before-and-after paintings. Lift a painted flap and bare trees burst into blossom, or geishas in kimonos in a cherry orchard give way to modern girls in T-shirts in an urban park — holes have been cut for the faces, which don’t change. In a series of paintings, ‘Looking Down on Tokyo’, Osuga broods on change from a personal perspective, towering like a lonely giant over the Lilliputian city of his childhood, shrunk with the years.

Time flies, and art helps us deal with it. For Hiroshige and Hokusai, Mount Fuji provided a fixed point in a floating world; for Osuga, though, the mountain is something of a cultural millstone. In his 36 ‘Views of Mount Fuji’, arranged in a grid on a single canvas, Fuji’s iconic silhouette appears in every frame, casting a baleful art-historical shadow. He sees it in a rubbish tip, a gravel pile, a conical bra, a half-opened umbrella, a lampshade, a castle pudding; he attacks it with boxing gloves, threatens it with a baseball bat, stands triumphant with one foot on its summit, but it won’t go away. In one self-portrait, a dismayed Osuga contemplates a Fuji-shaped zit erupting on his back; in another he is reconciled with the mountain and hugs it. Osuga’s art may be Western but his heart is Japanese, which makes him the perfect guide to Tokyo.

Comments