Today, February 28th 2013, is the 80th anniversary of the conclusion to one of the finest – and certainly the most controversial – test series ever played. Eighty years ago today, Wally Hammond and Bob Wyatt put on 125 for the third wicket as England strolled to an eight wicket win at Sydney. This capped a remarkable winter for the tourists and sealed a crushing 4-1 series victory. It remains one of English cricket’s greatest foreign triumphs.

Rarely before and rarely since has pure theory been so completely matched to the needs of applied cricket. No wonder Douglas Robert Jardine is still remembered as arguably the finest captain to ever lead an English side into cricketing battle and Harold Larwood still celebrated as perhaps the finest fast-bowler who ever took the fight to the Australians.

This, of course, was the Bodyline series. No other confrontation has provoked such controversy or inspired such a literature. DR Jardine may no longer be the most hated man in Australia but even 80 years later few Australians are minded to afford him the benefit of the doubt.

Not that the great man would have it any other way. The old Scots Covenanting motto “Christ and no quarter” could be said to apply to Jardine’s approach too. And since Jardine, like so many great Englishmen, wasn’t English at all I like to think his soul was infused with a measure of his Scotch ancestors’ presbyterian certitude and rigour.

The term “Bodyline” demonstrates the power of what political consultants these days call “framing”. Bodyline sounds so much more threatening, so much more venal, so much more not-in-the-spirit-of-cricket than “fast leg-theory”. Be that as it may, fast leg-theory was what it was and leg-theory was hardly a recent innovation. By some measures it had existed for a quarter of a century before Jardine ever unleashed Larwood upon an unsuspecting and easily-offended Australian public.

The difference was accuracy. Inaccurate Bodyline bowling might frighten a batsman but, provided he kept his wits (and his eye on the ball), it need not imperil his wicket far less, as sometimes suggested (chiefly by Australians) his life. Larwood, almost uniquely amongst its practitioners, had that accuracy. Though 16 of his 33 wickets in the series were bowled, his ability to make the ball rise from back of a length on the unresponsive Australian pitches of the era was remarkable.

Amidst the controversy of supposedly targeting the batsman’s body in preference to his stumps it is sometimes forgotten that despite all this Australia, who had the advantage of batting first in four of the five tests, were able to post respectable, though not daunting, scores in their first innings. First-innings scores of 360, 228, 222, 340 and 435 were countered by English totals of 524, 169, 341, 356 and 454. In the first of these, of course, Bradman was absent and Australia won the second test thanks to a century from the Don and 10 wickets from O’Reilly. In four of the five tests England enjoyed a half-time advantage but only twice was this a large supremacy. (It was the second innings what won it: Australia never passed 200 in their sophomore innings.)

All of which serves to remind us that one of the reasons this proved an epic series was that Australia fielded a terrific side themselves.

It is also sometimes forgotten how good Woodfull’s Australian side was. A lack of fast-bowling was its only weakness. Nevertheless Australia’s doughty skipper could, at various times, call on the talents of McCabe, Ponsford, Richardson, Kippax, O’Reilly and Grimmet. And then there was Bradman. Ordinarily his presence ensured that, effectively, Australia pitted 12 players against the opposition’s 11. Jardine’s challenge – and his achievement – was to even the odds. Reduce Bradman to mere mortal status and the game would revert to the traditional 11 vs 11.

And he did it. By god he did it. Many people attempted to solve the Bradman Problem; Jardine was the only man to do so. Even then it was, like Waterloo, a damn close run thing. Of the many brain-boggling statistics demonstrating Bradman’s pre-eminence one of the most startling is that while he made 29 test centuries he was only 13 times dismissed between 50 and 100. That is, having reached 50 Bradman was, over the course of his career, more than twice as likely to make a century as not. No-one has ever matched this.

Recall the scale of the challenge Jardine faced. In 1930 Bradman had flayed England for 974 runs at an average of 139. He made seven test innings that summer and reached at least a century in four of them. The following Australian summer he skelped the South Africans for 806 runs at an average of 201. His five innings that summer produced four centuries. As Percy Fender, Jardine’s captain at Surrey, had said in 1930 “something new will have to be introduced to curb Bradman”.

And Jardine had to find that something new for a series to be played on dull Australian pitches and in conditions unlikely to prove conducive to swing bowling. The prevailing conditions – including a still-batsman-friendly LBW law – dictated English tactics almost as much as did the need to counter Bradman. The ball would be softening after no more than 15 overs; allowing the Australian batsmen the freedom of the off-side would have been an invitation to make hay. Bodyline was a means of rebalancing the game, chipping away at the in-built advantage batsmen enjoyed at the time and (especially) in those Australian conditions.

Even so and even all these 80 years later there remains something gasp-inducingly cold about Jardine’s captaincy and tactics. Steve Waugh, another tough cookie, said his side’s goal was to reduce the opposition to a state of “psychological disintegration”. Australian commentators purred at this, conveniently forgetting how they loathed Jardine for applying precisely the same principle to his cricket. But Waugh was a piker in comparison with DRJ.

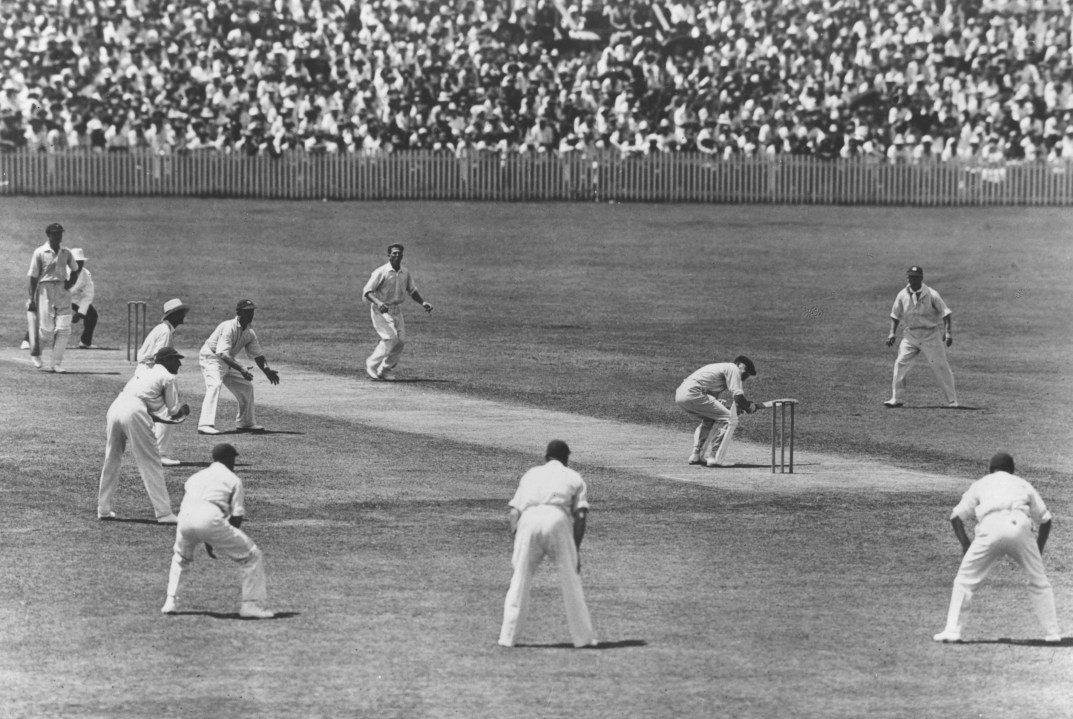

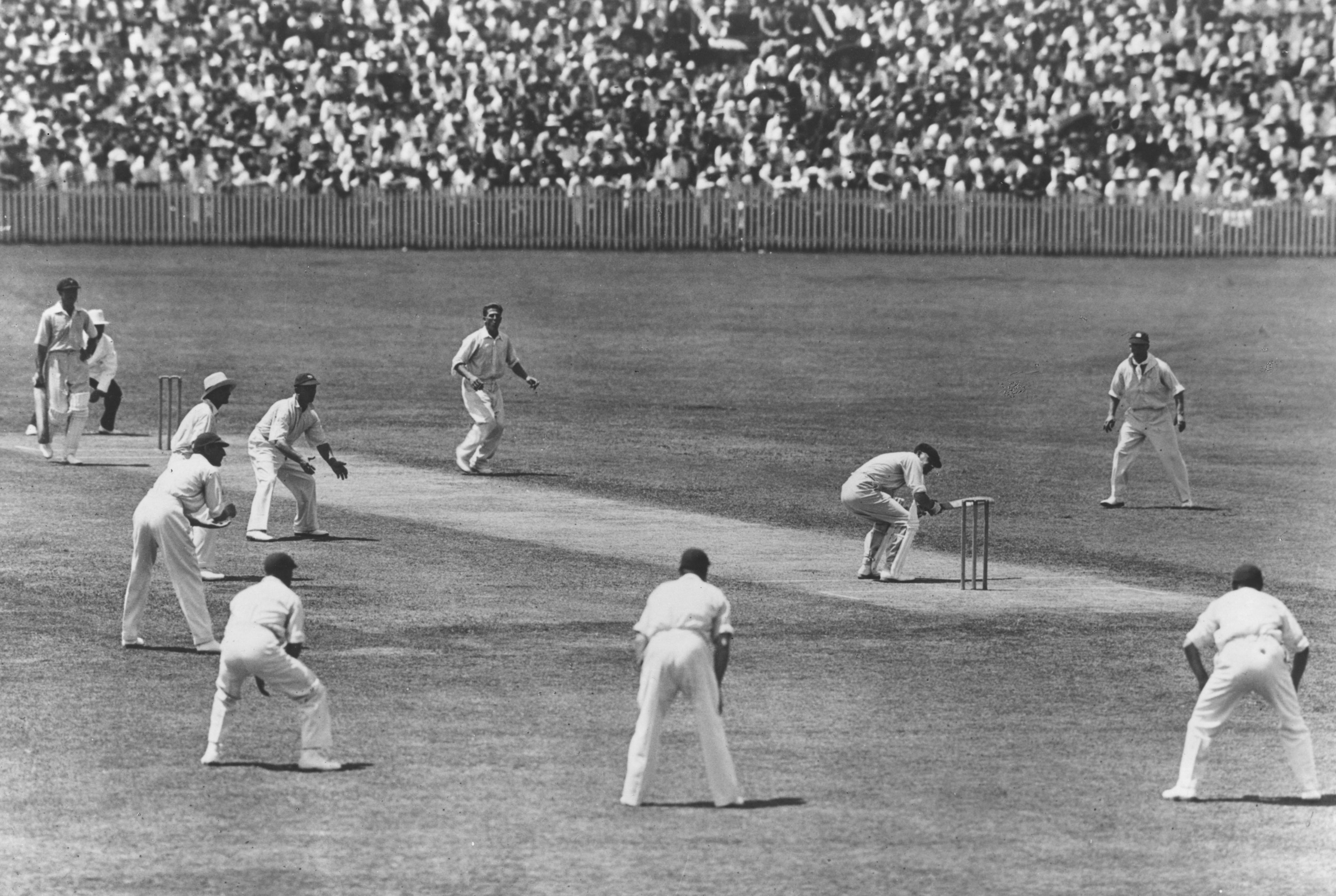

At Melbourne Arthur Mailey, that unusually romantic Australian troubador-of-spin, observed the essence of the hunt. In his newspaper column he wrote that “Just with a nod of his head Jardine signalled his men, and they came across to the leg side like a swarm of hungry sharks.”

A simmering pot came to the boil in the third test at Adelaide which England won by 338 runs. If this was, as Wisden recorded, perhaps (at the time) the “most unpleasant [test] ever played” the chief responsibility for that unhappy situation lay with the Australians. The series was at that point tied at one win apiece; the victorious side in the City of Churches would be well-placed to secure the Ashes.

The chief controversy arose when Australian batsmen were felled by English bouncers. But it is often forgotten that when Larwood struck Woodfull a heavy blow above the heart he was, at the time, employing an orthodox field. The same was true when Bert Oldfield ducked into a Larwood express and was hit in the head. The veteran Oldfield absolved Larwood of responsibility, admitting it was his own fault.

Woodfull, however, demonstrated that wherever you find a beaten Australian you’ll find a whinger. At the conclusion of the third day – the height of the on-field controversy – he dismissed Plum Warner’s dutiful visit to the Aussie dressing-room during which the English manager intended to inquire about the extent of Australian injuries with a phrase that remains famous to this day: “I don’t want to see you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there; one is trying to play cricket and the other is not. The matter is in your hands, Mr Warner, and I have nothing further to say to you. Good afternoon.”

They didn’t like it up them. But this was the moment the Ashes were won. As Woodfull writhed in agony, clutching his chest, the silence was broken by the English skipper. “Well bowled, Harold” Jardine said in a voice loud enough for all to hear and with a nod and a clap of his hands he signalled his fielders to move to their leg-theory positions for the very next ball. It was, amidst the baying and barracking, a masterstroke of cold-blooded captaincy and still, deservedly, perhaps the most famous change-of-field in the history of the great game.

Cricketing success is often relative. Bradman endured his least successful season that summer. In eight innings he made but a single century and three times he was dismissed between 50 and 100. He averaged 56 for the series. Still more than Hammond (who averaged 55) but, in the circumstances, reducing Bradman to Hammond’s level of performance constituted a great victory for England.

The Don adapted his method. Just as England attacked him so he attacked England. He scored at a clip of 74 runs per 100 balls that Australian summer. Both sides gambled. England sought to make life difficult for Bradman; the Don bet that he could score enough runs quickly enough to make up for the fact that, Larwood being Larwood and the English tactics being what they were, sooner or later a ball would arrive that had even Bradman’s number on it. He was half-right and he half-succeeded. That, in its way, is one of the greatest measurements of his unparalleled genius.

Extraordinary times demand extraordinary measures. But Bodyline was not quite the total war it is sometimes imagined. In the first place, even Larwood did not always bowl to a leg-trap. Secondly, neither Bill Voce nor, in the one test he played, Bill Bowes, proved able to match Larwood’s accuracy (neither were express-merhants either, of course). Thirdly, Gubby Allen, already a prig even then, refused to bowl Bodyline. And fourthly, of course, Hedley Verity did not take his 11 wickets with Bodyline either. In other words, Bodyline was a tactic used relatively sparingly. Perhaps no more than (at most) 25% of the overs England delivered that series were bowled to Bodyline fields.

Of course it all looks different in hindsight. Despite the later-outlawed leg-trap there is little reason to suppose that Bodyline targetted the batsmen in 1932-33 any more than Lillee and Thomson did in the early 1970s or than the great quartets of West Indian fast bowlers did later than decade and in the 1980s. For that matter, Australians had no complaint (and nor, really, did Englishmen) when Ted McDonald and Jack Gregory terrorised English batsmen on Australia’s 1921 tour of England.

Perhaps we would not wish every captain to approach the game with Jardinian ruthlessness. Cricket might lose something if that were the case. But that Jardine was a great captain whose task was, at least initially, seemingly hopeless cannot be sensibly disputed. Taming Bradman demanded extraordinary measures. Jardine and Larwood found and perfected those measures. Just as, if you will forgive the comparison, defeating Hitler demanded something out-of-the-ordinary, so did defeating Bradman. (One of Bodyline’s forgotten consequences: Bradman was converted to the cause of lobbying for a reform of the LBW law the better to bring back a measure of balance between bat and ball. This is part of Jardine and Larwood’s legacy too.)

The establishment – and despite Winchester, Oxford and Surrey Jardine was not really a member of the establishment – never forgave Larwood and Jardine for their success. Shamefully, Lords acceded to Australian suggestions that neither Jardine nor, especially, Larwood should face the antipodean tourists on their 1934 tour of England. The “crisis” in Anglo-Australian relations was almost entirely of the Australians’ making. Jardine was removed from the captaincy before the Australians arrived in 1934; Larwood never played for England after Bodyline.

And in 1934 Donald Bradman scored 759 runs at an average of 94.75. England lost the Ashes they had won so dearly in 1932-33.

As English cricket disowned the two men most chiefly responsible for one of English cricket’s greatest triumphs it is good to be reminded that Douglas Jardine never deserted his greatest ally. The story of the present DRJ gave HL is well-known. It was an ashtray engraved with the inscription: “To Harold for the Ashes — 1932-33 — From a grateful Skipper.” Less well-known is the telegram Jardine sent Larwood upon the latter’s emigration to, of all countries, Australia. Larwood bade a sad and lonely farewell to England, deserted by the cricketing establishment and consigned to a basket labelled best-forgotten by most. There was no send-off. With one exception. As the great fast-bowler boarded the boat to Australia at Liverpool he received a telegram. “Bon voyage,” it read. “Take care of yourself. Good luck always. Skipper”.

Larwood and Jardine were great men. They deserve to be remembered more fondly than they are. These were the men that slayed Bradman.

And yet they will not be celebrated, not even now. Such is the price of success. There remains something chilling, something otherworldly about Bodyline and the manner in which it is recalled. Even those of us who admire DRJ can admit cricket might be a poorer game if everyone played it as he did. I have had cause to quote some lines from Walter Scott’s Old Mortality before but they seem just as apposite to Douglas Jardine as they ever were to a Covenanting presbyterian fanatic:

Think you not it is a sore trial for flesh and blood to be called upon to execute the righteous judgments of Heaven while we are yet in the body, and retain that blinded sense and sympathy for carnal suffering which makes our own flesh thrill when we strike a gash upon the body of another? And think you, that when some prime tyrant has been removed from his place, that the instruments of his punishment can at all times look back on their share in his downfall with firm and unshaken nerves? Must they not sometimes question even the truth of that inspiration which they have felt and acted under? Must they not sometimes doubt the origin of that strong impulse with which their prayers for heavenly direction under difficulties have been inwardly answered and confirmed, and confuse, in their disturbed apprehensions, the responses of Truth himself with some strong delusion of the enemy?”

Indeed. But, despite this, Jardine contained multitudes. He considered village cricket the purest, noblest form of the game. His task was to fight in a different arena. Jardine and Larwood were fortified by the knowledge – sure in their own minds – that they were doing, if you will, the lord’s work. And damn the naysayers. Bradman, if you like and will allow me to shift literary comparison, was Jardine’s White Whale. But at least he caught his. The game would be poorer had neither Douglas Jardine nor Harold Larwood ever existed. We should remember that even if we also think or suspect it may be no bad thing not everyone is quite as superbly bloody-minded as two of English cricket’s greatest-ever heroes.

Timothy’s words could usefully be their epitaphs: I have fought the good fight, I have run my race, I have kept the faith.

Comments