No, they decidedly did not like us — this is true at least for the majority of the nineteenth-century British travelers to the New World. They came out of a sense of wonder, somewhat akin to the reaction of Thomas More who declared in his sixteenth-century Utopia that ‘nowadays countries are always being discovered that were never in the old geography books.’ Over the next few centuries, perhaps no emerging country west of the Atlantic would excite as much curiosity as the vast expanse of territory that would become known as the United States.

It soon became manifest that, in expanding her geographical borders, the United States had staked out a new social order. Was it not likely that this developing country, with its brash ideas, would find herself a pariah among the very nations she sought to rival? Would she be able — indeed, how did she dare — impose her new concepts on countries with longer histories? And when would she be mature enough to make significant contributions to global advancements in the sciences and the arts?

Most Europeans who found their way to nineteenth-century America were seeking new economic opportunities largely as immigrants, but there were those who came as eager investors. A sizeable group came out of curiosity. This last group invariably meant visitors who had both the leisure to make the transatlantic crossing and the education to render a detailed account of their stay. Few visitors from England who crossed the Atlantic as observers were shy of being candid in their reports; no one, however, can be said to have been as vituperative as the fulminating Frances Trollope. Her book, Domestic Manners of the Americans, proved to be truly offensive to the emerging nation, for Americans were not always as certain of their country’s political, economic and social achievements as they often professed. Yet Trollope was right in many of her judgments.

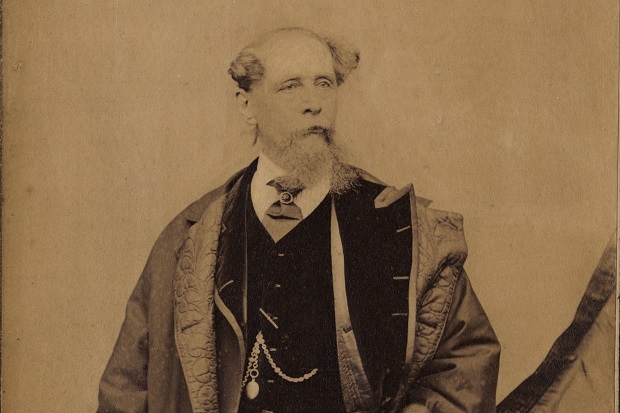

Some fifteen years later, when Dickens followed Mrs. Trollope, he had his own reasons to be displeased with the New World: chiefly, the lack of copyright to protect his income from reprinted books. Thackeray’s very guarded impressions can be learned through the many letters he wrote back home, while the prevailing view of a young Scottish captain named Basil Hall was that America did not represent a new and audacious experiment in equality but was distinctly one of England’s ‘occasional failures’. There were two more English “Fannies” who came: Frances Wright and Fanny Kemble. Wright felt that she had the answer to slavery, while Kemble was convinced that America would revert, before long, to a monarchy because ‘the feeling of rank, of inequality, is inherent in us, a part of the veneration of our natures.’ Thomas Colley Grattan endured a stay of seven years in America as a British Consul: so long a residence in the New World, he was convinced, must be felt by a man of European tastes and habits as a ‘banishment’. The pro-Union stand of journalist Edward Dicey during America’s Civil War set him apart from most British journalists and was in distinct opposition to the anti-Union cause adopted by the British government. Oscar Wilde brought his new aestheticism to America, while Henry James came with an insider-outside point of view that is as revealing as it is perspicacious.

Clearly, all of these visitors recognized that the rising nation had none of Europe’s historic grandeur. Would it one day? That was the question.

Passage to America: Celebrated European Visitors in Search of the American Adventure by Gloria Deak is published by I.B. Tauris. (£20)

Comments