Just as there are people who are their own worst enemies, so there are books that are their own worst reviews. Mark Griffin’s A Hundred or More Hidden Things, a new biography of the Hollywood film-maker Vincente Minnelli, is one such. No review could possibly be as damning as a verbatim reproduction of its irresistibly putrid pages.

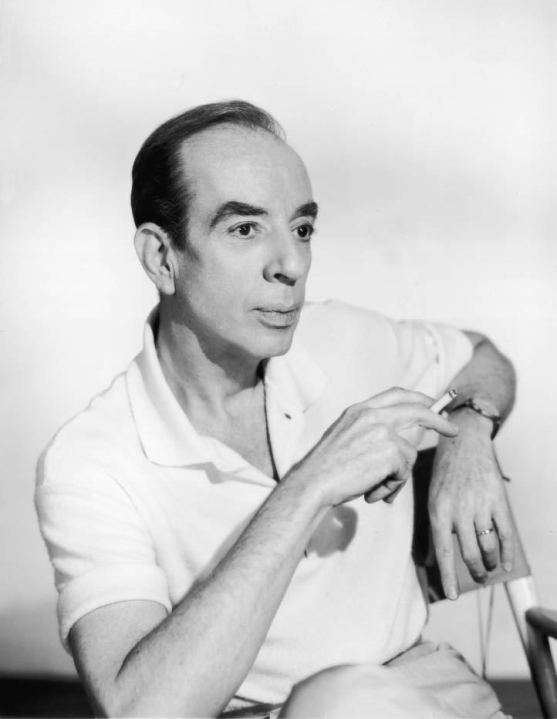

Minnelli’s achievement certainly does merit attention. In fact, for the auteurist critics of Cahiers du Cinéma, who argued that a film’s distinction derived primarily, even exclusively, from the degree to which it reflected its director’s own personal visual and thematic preoccupations, his was practically an open-and-shut case. At least to the initiated, a Minnelli film is instantly identifiable not only by the poise with which the unfailing gorgeousness of its ‘look’ is held in equilibrium between the routinely heightened, glamourised naturalism of a typical Hollywood product and the flagrant stylisation of a stage musical (it was from the Broadway theatre that MGM initially recruited him), but also by his recurring theme of the alienated outsider seeking solace in a more hospitable dream-world.

‘Onirique’ — or, in the little-used English, ‘oneiric’, meaning dreamlike, semi-surreal — was the word to which the auteurists almost automatically had recourse when defining work, musicals, melodramas and comedies alike (Meet Me in St Louis, The Band Wagon, Lust for Life, Some Came Running, Gigi). He was, in a sense, the quintessential Hollywood director, since his characters’ unarticulated cravings for myth, colour, fantasy and wit could be said to exemplify the universal appeal, the very raison d’être, of the entire postwar American cinema.

But he was equally a quintessential Hollywood auteur, because the ambiguity of his filmic sensibility has frequently been interpreted as mirroring his own troubled sense of self as a screamingly obvious homosexual who wore green eye-liner from his adolescence on, yet also married four times and fathered two daughters, the more famous one being Liza. Like that of virtually every comparable Hollywood director, his career was uneven. But if the failures (Brigadoon, Kismet, The Reluctant Debutante) resembled boxes of chocolates with too many soft centres and no second layers, the finest were masterpieces.

Now (groan) back to the book under review. Although Griffin claims to have watched the films a dozen times, he hasn’t seen a thing. His introduction aside, in which he rather touchingly relates how, as a small-town teenager, he sneaked off alone to On a Clear Day You Can See Forever instead of accompanying his high-school friends to Return of the Jedi, becoming thereby something of a Minnelli protagonist himself, he has no intuitions to offer, let alone analysis. For him the director was a juggler of soap bubbles, a campy flibbertigibbet in a canary-yellow jumper and scarlet slacks. He can make no sense whatever of Minnelli’s sexuality and, to cap it all, he writes atrociously.

The least of it is a matter of crude Variety-ese. In Griffin’s world films are not directed but ‘helmed’, screenplays not written but ‘penned’, actors not cast but ‘tapped’, Oscars not won but ‘snared’ or ‘copped’. Among the numerous experts he interviewed are ‘former contract dancer Judi Blacque’, ‘Judy Garland historian John Fricke’, ‘Minnelli disciple John Epperson’ and, presumably to add a little Limey gravitas, ‘writer and Minnelli enthusiast Sir Gerard Kaufman’. Maxim’s becomes ‘the legendary Paris eatery’, Cyd Charisse was so incomparably lightfooted she must have been ‘beamed direct from Planet Flawless’, the remake of Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was destined to be so spectacular a super- production it had to be updated and upgraded to ‘no less a global conflict than World War II’ (the original silent version was set in World War I) and the producer, Pandro S. Berman, is described unforgettably as having once been ‘a Ball beau’ (ie an ex-boyfriend of Lucille Ball). Griffin appears not to know the meaning of ‘disinterest’, the difference between ‘faze’ and ‘phase’, and, from a list of howlers too long to itemise, the fact that, as Diaghilev never once travelled to America, it’s more than unlikely that he befriended the young Minnelli in the New York of the Twenties.

A Hundred or More Hidden Things is, in short, a prize hoot. If a book can be both unreadable and unputdownable, then this is it. Yet, ultimately, the one and only constituency of readers to whom it may be recommended are those who, as Griffin himself expresses it with his usual ineffably cheesy panache, ‘horde their Playbills, worship Carol Channing and have blazing marquee lights permanently reflected in their eyes’.

Comments