It can’t be easy to switch between editing others people’s fiction and writing your own: how do you suspend that intuitive critical impulse? Gordon Lish, who is best known as the editor of Raymond Carver’s short stories but has also written plenty of fiction in his own right, is familiar with this dilemma, and in White Plains (Little Island Press, £18.99) he has fun with it. These stories are replete with parenthetical um-ing and ah-ing over synonyms, punctuation and grammatical solecisms — a prolix testament to the agonies of prose composition: ‘Losing tone here, not retaining purchase on stance here, falling to pieces with the coward’s frolic along the phraseological here.’ When Lish declares, at the outset of one story, that ‘every utterance in this book has been coddled’ he really means it.

The material collected here ranges from short fictions such as ‘Naugahyde’, a terse, elliptical dialogue between a married man and his mistress, to meandering soliloquies such as ‘Declaration of Dependence’, in which the author gives out his personal telephone number and encourages the reader to give him a call ‘only if you are… feeling truly “up” to it and “up” for it’. Lish’s riffing whimsy and winkingly mannered prose style won’t be everyone’s cup of tea; readers who wish to preserve their sanity would be well advised to dip in and out of White Plains, rather than read it in one stretch.

Altogether more accessible is Joshua Ferris’s The Dinner Party (Viking, £14.99) which teases wry humour out of stagnant or moribund relationships in contemporary New York. A man who comes clean about an affair pleads, in mitigation, that everybody else is at it too; a woman consoles her sexually underperforming partner with a damning pat on the head. Ferris gently lampoons the hapless obliviousness of his male protagonists, who are jolted out of their complacency by the decisive actions of their partners. In their sensitive rendering of the emotional distance that opens up — often with jarring suddenness — in the terminal phase of formerly intimate relationships, these vignettes call to mind Joseph Conrad’s poignant observation that ‘We live as we dream — alone’. But there are also flickers of warmth. ‘The Breeze’ depicts the restlessness of a woman whose boyfriend is an inveterate homebody; her enjoyment of their evening on the town is ruined by her niggling sense that she is missing out on ‘the possibility of a different night, better companions, competing visions of a finer life’. It feels for all the world like yet another break-up is in the offing, but the story ends on an ambiguous note, so perhaps they will muddle through.

Mary Gaitskill’s Don’t Cry (Serpent’s Tail, £8.99) offers a bleaker take on male-female relations, and sex in particular. In ‘An Old Virgin’, a doctor indulges in unwholesome speculations about her patient, a fortysomething virgin: ‘she imagined her virginity like a strong muscle between her legs, making all her other muscles strong, making everything in her extra alive’. ‘Mirror Ball’ is a parable about a casual encounter in which the man holds back his ‘soul’ whereas the woman is afraid of giving hers away; when she relents, ‘Her little demon consorts punched their fists in the air and cheered.’

This framing of sexual contact as ‘a humiliation of our personal particularity’ implies a somewhat passive and pessimistic view of female sexuality, and the priggish vibe is not helped by some rather icky descriptions: a young woman’s vagina is ‘her warm spring darkness’, and a man performs cunnilingus ‘like a bear… picking berries with the elegant black finger of its tongue’.

There is nonetheless something grimly compelling about the Darwinist biological determinism that informs Gaitskill’s interest in ‘the crude cinder blocks of male and female down in the basement, holding up the house’. A conversation in the collection’s opening story, pointedly set at the start of the Reagan years, establishes the mood: ‘Weakness is really… evil in a way. It’s like being connected with the ugly things in the world. You’re the clubfooted straggler endangering the herd. You make people depressed and sentimental.’

Jim Shepard might want to steer clear of Gaitskill’s book. In an impressively futile gesture, Shepard some time ago declared war on the psychological turn in fiction — what he calls ‘the tyranny of the epiphany’. To this end the stories in The World to Come (Riverrun, £16.99) are resolutely plot-driven, and firmly situated in the material world: civil and military infrastructure features prominently, as does ecology.

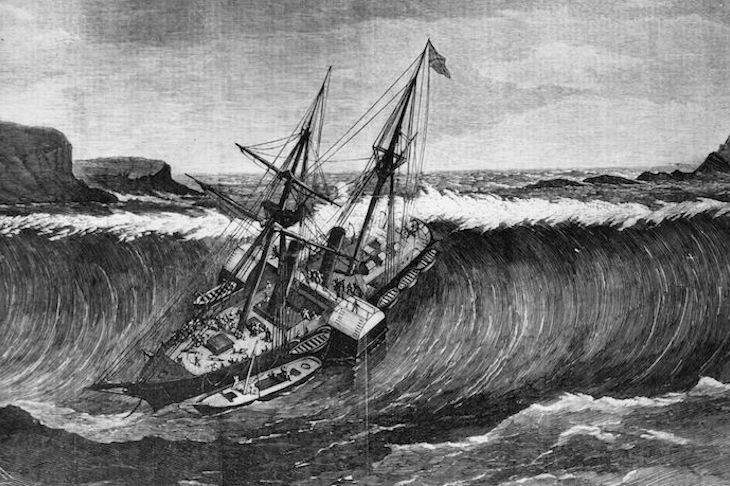

‘Safety Tips for Living Alone’ tells of a disaster in which an Air Force base in the Atlantic is a destroyed by a storm, killing many servicemen. The narrative alternates between the unravelling of the disaster and the distress of the wives back home. Concerns had been raised about the safety of the structure, and ignored; state incompetence was to blame. Similarly, the narrator of ‘Positive Train Control’ laments the deregulation of rail safety and its deleterious impact on the management of hazardous materials. Elsewhere we have a journal of a 19th-century sea voyage, an account of a

17th-century volcanic eruption leading to a tsunami, and a plodding tableau of agrarian hardship. (‘The most fortunate of us persist without prospering.’)

The collection’s overriding themes — a plaintive mistrust of governmental authority, and timorous awe at man’s impotence in the face of nature’s destructive power — are apposite to our times, but the competently pedestrian prose belongs to an earlier era.

Comments