In the 1820s and 30s, London used about 20 million goose quills a year. The government’s Stationery Office on its own was still getting through half a million a year in the 1890s, roughly a quill a clerk a day. The administration of Victorian Britain and its global empire rested on a vast flock of geese. So fierce was the demand for quills that many were pulled from living birds, a process that was agonising and sometimes fatal. Travellers in rural England occasionally found denuded goose bodies lying quill-less at the side of the road where the quill robbers had left them shocked to death. Only the invention of the type-writer released the goose population of Britain from centuries of pain.

This enormous and dazzlingly encyclopaedic history of our relationship with animals over some 900 years is, largely, a tale of such barbarity and imposition. If we needed it, or wanted it, animals were made to provide it. One Puritan writer of the 17th century maintained that the creation of animals was God’s way of keeping meat fresh. That expectation of dominance lies behind a long story of use that carelessly drifted into abuse, of abuse as a form of delight, of a kind of intimacy with the animal world which generated behaviour that seems now merely weird. Most 17th-century recipes for rabbit pie insisted, for example, that the head and ears should always to be left on. There was to be no concealing of the nature of the prey in an anonymous stew or a deep-fried nugget. Sometimes the ears of the rabbit were threaded through so that they lay along the top of the crust, giving no doubt as to the contents beneath.

Why? And why does this seem so distant from us? Arthur MacGregor, who until recently was curator of antiquities at the Ashmolean, carefully uses the super-neutral word ‘Interaction’ in the title of his monumental book, but this is not, with some exceptions, a tale of symbiosis. It is a chronicle of brutality — the wrong word; ‘humanity’ — particularly when it comes to entertainment at the expense of animals. At times it reads like the account of a sustained mass lunacy, of a kind of rage, hatred and criminal indifference taken out on creatures that were caught and shut up so that they could endure it. Why, apparently, did our ancestors have none of the empathy most of us now feel for the animals that share our lives? How can they have been so blind to what they were doing?

There may a connection between that cruelty and the sheer omnipresence of animals in pre-modern life — and between our distance from them and our affection for them. Did they simply abuse their animals in the way we abuse our cars? Did they use them in the way we use plastic bags? But Dr MacGregor doesn’t enter the territory of motive or meaning. There is almost nothing, for example, about pets here; or the chronic abuse of animals by scientists; or of religious attitudes to them. For all of that Keith Thomas’s Man and the Natural World still reigns supreme. Instead he documents richly and marvellously untold examples of how we treated the beasts.

Some are beautiful and charming: Izaak Walton tying ribbons on the tails of young salmon and looking out for those same ribbons a year later as the fish returned from the sea; or the court fashion in the 17th century for taming cormorants who, with another ribbon tied around their necks to prevent them swallowing their prey, could be taught to fish for their masters. The careful Enlightenment programmes for stock improvement are all described here in full and loving detail.

But most of it is not like that. The Victorian huntsman Captain L.C.R. Cameron liked to eat the hearts of otters ‘roasted with butter and herbs’ at a celebratory dinner at the end of each hunt. A hundred years earlier, foxes had been hunted so effectively in England that an international trade in cubs had been established. (Elizabethans were already preserving foxes for hunting.) In Victorian England, 1,000 cubs a year, most from Holland, Germany, France and Scotland, were being sold in Leadenhall Market, 10s to 15s each.

From there they were sent off down to the shires to be raised as ‘bagged foxes’, brought to the meet in a sack, let go a few minutes before the hounds and then chased. But for the finer sensibilities, bagged foxes weren’t satisfactory. Their terror made them stink so much that the hounds could simply stroll after them like a party of Bisto kids with their noses lifted to the whiff of gravy. Other bagged animals, ‘broken in spirit’ and stiff-limbed, dumped out in country they didn’t know, with a pack of hounds hot on their heels, simply gave up and had themselves eaten.

The industrialised world did nothing to release animals from their hell. The sheer imposition of labour on animals, their lives worn out with the work we made them do, steepened with the Industrial Revolution. Horses were the motive power for Arkwright’s mill in Nottingham, where a 1,000 spindles driven by nine horse wheels required 36 horses to operate them, day and night all year, and for untold numbers of hoists, mills and pumps. Every pre-modern building you see represents a prodigious quantity of animal labour, huge lumps of stone drawn by oxen up impossible slopes, vast baulks of timber hauled for days on end through Sussex clays. The horses that drew the 19th-century London omnibuses, each weighing 3½ tons with a full load up, were usually brought in from the country at five years old for £35, made to work for five years on the London streets, at the end of which, if they survived, their value had sunk to £5. Two out of three such horses never made it to their full term but died in service, when ‘they might fetch 35s from a cat’s meat man’.

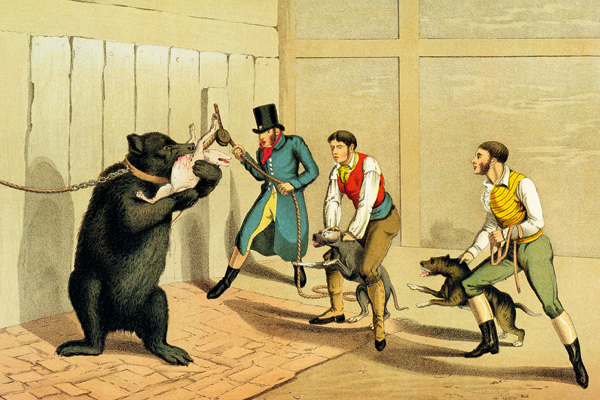

The most gripping of all this book’s sections — for its horror — is on urban and rural sports. In 1544 the Duke de Najera on visiting England was given a particularly English entertainment:

a pony with an ape fastened on its back, and to see the animal kicking among the dogs, with the screams of the ape, beholding the curs hanging from the ears and neck of the pony, is very laughable.

Not that everyone approved of such delights. The Puritans, who were the first to treat their children kindly, were also disgusted by the abuse of animals. It is true that the reaction could sometimes take odd forms. When a party of parliamentarian troopers entered Uppingham in 1642, they found the citizens enjoying some bear baiting. The troopers seized the bears, tied them to a tree and shot them. The Colonel Pride who purged parliament also slew all the bears on the South Bank in London and shipped the dogs (along with most of London’s prostitutes) to Barbados.

But the atrocities returned with the Restoration. Harry Hunks, George Stone, Besse of Ipswich and Moll Cutpurse (all bears) suffered long careers of being attacked by dogs for public entertainment. Seventeenth-century gentlemen invented leather lilos, called ‘windbeds’, with a pipe at the corner which could blow air into them, and a stopper attached, on which they could lie listening to their terriers fighting foxes in the earth below them. Others liked to hang a goose from a convenient branch by its legs so that horsemen could take it in turns to try to seize it by its well-greased neck as they rode underneath. To make badger baiting more even-handed, they liked to cut away the lower jaw of the badger to give the dogs a better chance. Even as late as 1789, young guns had their accuracy improved by the instructor tying small pieces of white paper around the necks of captive sparrows which were then thrown into the air in front of the apprentice gun. ‘It affords excellent diversion in seasons when game cannot be pursued, or in wet weather from underneath the shelter of a shed, or a barn door.’

No age has a monopoly on cruelty and to have poisoned the rivers in the way we did in the 1950s and 60s almost certainly was crueller to more otters than any otter hunt ever was. We now perform our destructions silently and secretly, part of the cynical mumsifying of modern life, the concealment of persistently exploitative behaviour under a fluffy strokable coat of loving Labrador softness. That is one of the reasons Dr MacGregor’s book is so valuable: it deals with unadorned realities.

Comments