‘Luxury high-rise duplex: lower floor comprising entrance hall with recessed guard posts, grand reception area, kitchen with crockery store, larders and walk-in fridge, armoury and staff WC; upper floor comprising master bedroom with two en-suite bathrooms, staff accommodation, guard rooms and safe deposit. Property provided with the latest hi-tech security systems and 24-hour manned guarding.’

Apart from the lack of a cinema and a gym, this property sounds just the ticket for the jittery billionaire looking to invest in London real estate. But its location is not the fringes of Hyde Park or the South Bank, it’s the side of a mountain near Xuzhou in northeast China, and its accommodation is designed not for the living but for the dead. Its suite of 19 rooms was cut into the rock of the Beidongshan Hills as the final resting place for a 2nd century BC King of Chu, and its contents are currently on display at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge in the first UK exhibition devoted to the Han dynasty. Alongside grave goods from the tombs of the Kings of Chu, the 300 exhibits include ravishing finds from the tomb of Zhao Mo, a contemporary ruler of the vassal state of Nanyue in Guangzhou who liked to style himself ‘emperor’, and had tastes to match.

The Han dynasty, which ruled for four centuries from 206 BC to 220 AD, laid the foundations of the Chinese way of life — administrative efficiency tempered by Confucianism — and maintained an equally civilised way of death. For a culture believing in a twofold soul — a sentient body-soul ‘po’ that returned to earth and a spiritual soul-soul ‘hun’ that floated away into the ether — immortality meant keeping body-soul and soul-soul together. To retain the ‘po’ in the body, the body had to be fed and watered, but it also had to be protected from the demons who would do their damnedest to get in and introduce decay.

Appearances demanded that in the afterlife the king and his concubines (who accompanied him on his last journey) were kept in the style to which they were accustomed. Catering standards had to be maintained. The King of Nanyue’s storeroom held a 100-strong batterie de cuisine, including a bronze double boiler and an ingenious design of insect trap that Richard Dare might think of reissuing. Should supplies run low, there was a substantial kitty: more than 52,000 coins were excavated from Beidongshan. If you were a Han royal, you could take it with you — and that included your staff. The knowledge that they would be sacrificed with their masters presumably made royal food inspectors extra vigilant — the King of Chu’s was rewarded for life (and death) long service with the rather cold comfort of a jade pillow.

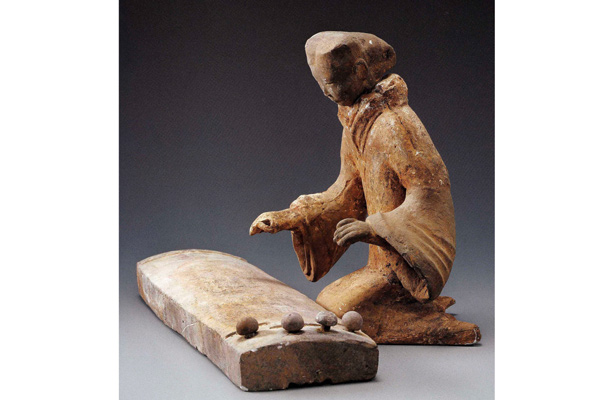

But man cannot after-live by bread alone; eternity drags, and entertainment is needed. Alongside painted terracotta models of servants and guards, Han tombs were staffed with troupes of clay actors, musicians and dancers throwing exotic shapes with their trailing sleeves. The performers were models, but the instruments were real: fish-shaped terracotta maracas, stone chimes and bronze goudiao bells. The gilt bronze mini-mountains harbouring mythical beasts that served as bridges for the stringed instruments in Zhao Mo’s post-mortem orchestra are among the most exquisite artefacts in the show.

Of equal importance to food and fun was security against intruders, demonic and human. The King of Chu’s tomb was manned by China’s second largest terracotta army and fitted with state-of-the-art self-locking doors, while the King of Nanyue was buried with a personal arsenal of 40 weapons of bronze and iron. Against non-human intruders, however, the best defences were made of jade, a material credited with magical demon-repelling properties that could throw a protective cordon around the corpse — starting with orifice plugs for the obvious entry points and ending with a full suit of armour, or robotoid onesie, fashioned from thousands of jade plaques. The two fabulous examples in the show are the first to leave China. To be on the safe side, the wearer could be further encased in a jade-inlaid coffin, of which a unique— and timelessly modernist — example from Beidongshan is also on show.

For an exhibition of ‘treasures’ there’s surprisingly little gold, a metal more closely associated with the Han’s Mongolian neighbours — one exception is a beautiful belt plaque embossed with a wolf attacking a bear. But for me the most imposing relic of Han civilisation is the carved stone toilet from a tomb at Tuolanshan. If plumbed in, this majestic throne — complete with disabled support arm — would still be serviceable. Unlike much of the Chinese merchandise now swamping the market, Han dynasty grave goods were built to last. They may not have bought their owners eternal life, but they did buy them immortality — although only after their defences were breached and the archeologists got in.

Comments