It is often said that the age of letter-writing is past. This forecast seems to me premature. I have edited three volumes of letters, in each case by writers labelled (though not by me) as ‘the last of their kind’. Yet here is another one, and I feel confident that more will follow. Few now write letters, but those who still do tend to take care what they write. And it will be some decades before we have used up the legacy of the living.

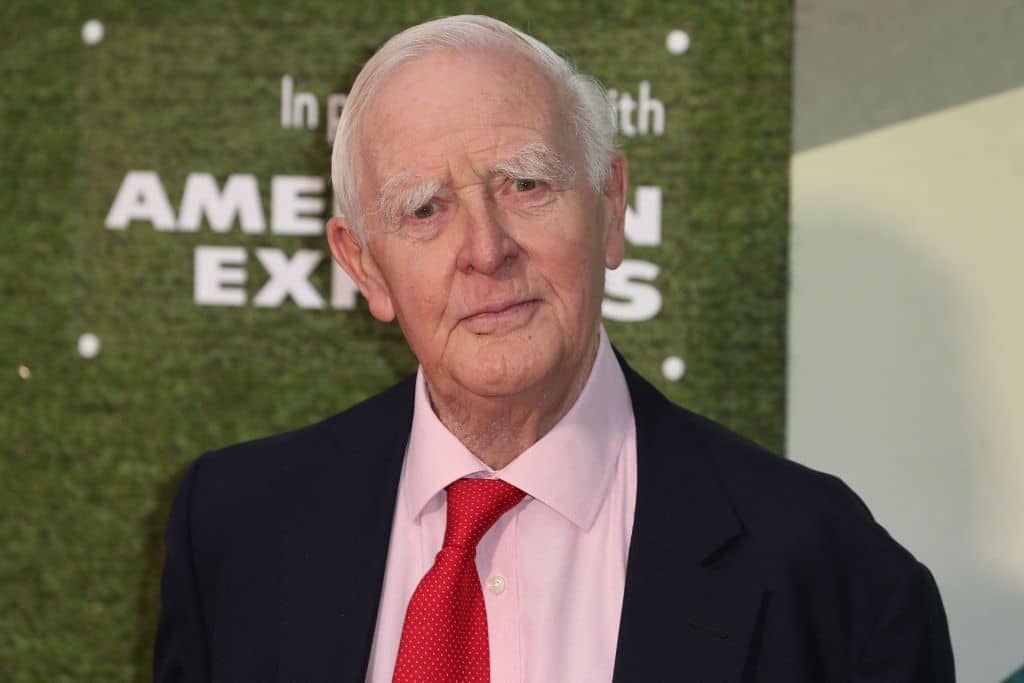

John le Carré, who died almost two years ago at the age of 89, was one such. His work is likely to be reassessed over the next few years and his place in the canon is not yet secure. But he is undoubtedly the pre-eminent spy writer of modern times, and arguably the definitive chronicler of the Cold War. At his peak he was very good indeed. Philip Roth judged A Perfect Spy (1985) to be ‘the best English novel since the war’. As a novelist, le Carré aimed high, with Dickens as one of his models. Writing mattered to him perhaps more than anything else.

So it is no surprise to find his letters well-written and entertaining. In them he is by turns affectionate, touchy, encouraging, witty, self-deprecating, egotistical, kind and even (as a young man) camp. The letters provide a narrative of his life from schooldays onwards, so that it is possible to read this book as a form of autobiography – though readers should be cautious of believing everything he writes.

For one thing, he is looking over his shoulder to posterity, almost from the start. ‘I have decided to cultivate that intense, worried look and to start writing brilliant, untidy letters for future biographers,’ he writes, while he is still an obscure crime writer yet to taste success. Like a number of the other letters in this volume, this one is illustrated with a clever cartoon, a distinct bonus for the reader. (To my regret, he refused to allow me to use any of these in my biography, published in 2015.)

Writing mattered to him perhaps more than anything else

Some of the best letters in this collection are written to one of the models for George Smiley, Vivian Green, and to Alec Guinness, who played the character on screen. The later ones tend to be less fun to read, especially those sent by email and typed by others, which are inevitably less personal. But even in some of those written by hand, there is a sense of a newsletter, such as one might expect to receive folded inside a Christmas card – except that they detail not children’s GCSE results but le Carré’s film options and shooting schedules. One minor surprise is that such a clever, well-educated man was a poor speller, writing ‘dilinquent’, ‘V. Wolfe’ and ‘Rosenkranz & Guildenstein’. It seems that he was dyslexic, a fact that he kept quiet about.

In writing about le Carré, whose real name was David Cornwell, there is always a problem of nomenclature. Though almost all the letters are signed ‘David’, the editor has taken the sensible decision to refer to him by his pen name throughout – even though, as the youngest son of le Carré’s first marriage, he is referring to his father. Indeed one of the footnotes mentions his own birth.

Tim Cornwell, who died as this book was going to press, has proved an excellent editor. He has chosen carefully and found some interesting letters that escaped me, particularly the ones to his stepmother Jane. He has arranged them thematically, with helpful introductions and explanatory footnotes. I should have liked a few more of these. Readers may realise that ‘Odders & Sodders’ is slang for le Carré’s publishers Hodder & Stoughton; but how many will know that Bosla is character in The Duchess of Malfi, or intuit that (as I assume) ‘Flea’ is a nickname for le Carré’s eldest son, Simon? They might also like be told whether his American correspondent William Burroughs was the notorious William S. Burroughs, author of The Naked Lunch, who admitted killing his second wife during a drunken ‘stunt’. In fact he wasn’t, but I had to do some research to find this out. However, these are quibbles, and it is possible for an editor to provide too much annotation rather than too little. Overall, Cornwell has done his father proud.

Had he still been with us to read it, le Carré might have been less delighted by some of the revelations in a memoir by his self-styled mistress Suleika Dawson. She tells us, for example, that they spent their first night together in Tim’s student bedroom. (At least he had changed the sheets beforehand.) What are we to make of such intimate disclosures? No doubt some will find them distasteful. But those interested in le Carré will discover much fascinating detail in Dawson’s kiss-and-tell.

They first met in 1982, when he came into a Soho studio to record an audiobook version of his recently published novel Smiley’s People, which she had condensed and adapted for the purpose. (Unlike most writers, le Carré was a superb reader of his own work.) There followed a long, flirtatious lunch at which he stroked her hand and kissed the tips of her fingers. Then he disappeared from her life for almost a year, before they met again to record another audiobook, this time of The Little Drummer Girl. He inscribed a copy ‘For lovely Sue, who shortened it…’

Within days they were lovers. He was then 52, married for 11 years to his second wife, Jane, with whom he had a young son – a sophisticated, seductive, handsome man, at the height of his powers, with enough money to do anything he wanted.

Dawson was half his age, though she had already shown a penchant for older men, and indeed had dated and been briefly engaged to someone even older than le Carré, the comedy writer Jeremy Lloyd. (She does not tell us whether the novelist, who fancied himself a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature, relished being next in line to the writer of Are You Being Served?) She became his mistress, accompanying him on trips abroad, nibbling caviar, glugging Krug and luxuriating in five-star hotel bedrooms while he padded off to lie fluently to his wife on the telephone. He bought a flat in St John’s Wood for their assignations, supposedly so that he could work there undisturbed. On one occasion she arrived in high heels, a Burberry raincoat and nothing else.

As this anecdote suggests, there is plenty of sex in the story and, from what she tells us, that side of the relationship worked very well. But everything else was tortured. The fear of discovery was a constant source of tension, resulting in some excruciating scenes, one at a Greek airport, where to his horror the cheating husband spotted one of his sons at a nearby carousel.

The secrecy involved meant they would almost never meet without one or two dates being cancelled or re-arranged. And almost as soon as they began their affair, le Carré spoke of calling it off. ‘Shall we say it’s over?’ he asked her, towards the end of a stay on Greek island, after they had been together only a month. ‘Because it won’t ever get any better than this, my darling.’ Yet almost in the same breath he claimed that she had become his muse, and agonised about leaving his wife for her. ‘Hold on, my darling,’ he told her over an illicit lunch. ‘It’s not going to be easy and it’s not going to be quick… But I’m heading for the shore.’ For almost two years he would zigzag between these two contradictory positions, repeatedly setting decision dates and then postponing these.

If all this sounds like a cliché, perhaps it was; but it must have been bemusing for a young woman, even one as intelligent and perceptive as Dawson. Le Carré had an odd habit of addressing her in the third person, as if she weren’t present. ‘Would a girl like a little cottage so as to be handy for her lover, and maybe a starter-kit car to get her there?’ He suggested a deux-chevaux; she would have preferred a Golf and a flat in Chelsea.

After almost two years she managed to break it off; but 14 years later, in 1999, they resumed, after she went to see him speak at a book event. The end came six months later, after she remonstrated with him for sending her a wad of cash to buy a plane ticket rather than whisking her off, as he had done previously. It was perhaps too obvious a reminder of the reality of their relationship.

One conclusion that emerges from this rather sad memoir is that what mattered most to le Carré was whatever he was writing at the time. Dawson was forced to endure the constant threnody about the book, how everything and everyone was taking him away from it, including the time he spent with me. There were unceasing complaints about his wife, his family and whomever else he felt encumbered by, which appeared to be everybody.

In different ways, these two books provide a vivid sense of this complex, driven, unhappy man. During his lifetime le Carré guarded his privacy jealously. Now that he is dead, perhaps we can get to know him better.

Comments