In 1971, at the height of the Indo-Pakistan war, my parents took me with them to Bombay. I was ten and it was my first trip abroad. My father worked for Brooke Bond, and had ‘tea business’ to attend downtown. First we checked into the Taj Hotel. On the waterfront, beggar children with lurid wounds and deformities were shaking tins at passers-by. The poverty unsettled me. The Taj was swank, I could see that, but outside all was dirt and destitution. (At a cinema nearby, jarringly, Carry on Loving was being advertised as the comedy ‘fillum’ sensation of the year.) Over dinner, my parents explained that Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan, was under attack. Bombay seemed strange enough to me.

I was reminded of my schoolboy visit to Bombay while reading Beautiful Thing, Sonia Faleiro’s bleak investigation into the city’s underworld of bar dancers and sex industry workers. Born in India in 1977, Faleiro does not flinch from addressing her country’s social inequalities. Even the vilest and most crime-infested alleys of Bombay are no deterrent to her as she seeks out waifs and strays to interview for this extraordinary non-fiction.

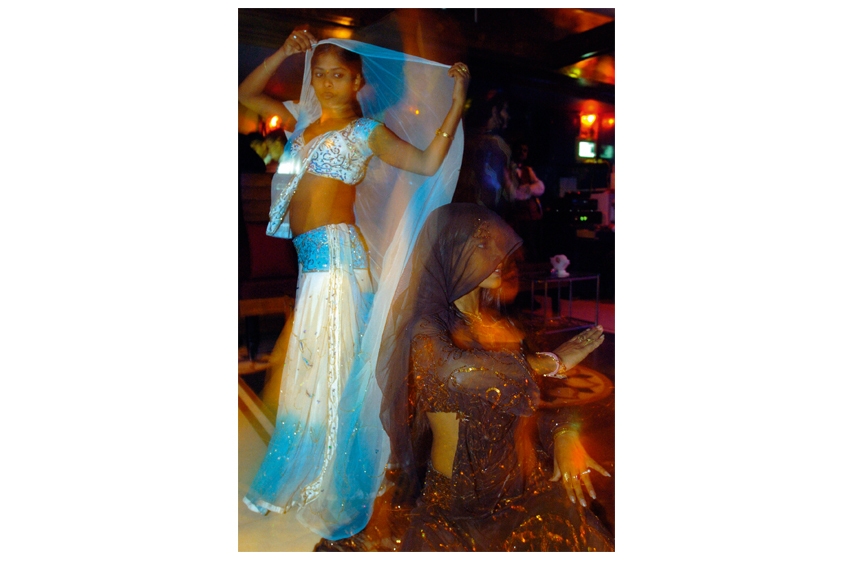

Beautiful Thing is the product of five years spent in the sleazier parts of the city known today by its Hindi name of Mumbai (Faleiro opts for the Anglicised version of Bombay). It is written with a novelist’s ear for dialogue and narrative pace, and with an affecting human empathy. Until the government banned them in 2006 (on the grounds of immorality), an estimated 1,500 dance bars existed in the Maharashtra state of which Bombay is capital. Runaway teenage girls were drawn to them in the hope of a better and more remunerative way of life. Many of the girls had been raped at home, or sold to scamsters of one stripe or another.

One such is Leela, a 19-year-old bar dancer of ‘magnetic vivacity’, who wants only to be like the models on L’Oréal hoardings: fetchingly pale-skinned, rake-thin. For all her street savvy, Leela maintains her Hindu faith in Ganesh, and collects plastic figurines of the elephant god. Her father is an alcoholic, with a corrosive sense of social inferiority and grievance. Back home in Uttar Pradesh he had abused both Leela and, repeatedly, his wife. Sexual abuse of country girls like Leela remains a shameful commonplace of rural India, says Faleiro. Seeking help from the police is often seen as an act of betrayal; Indian girls are expected to bear their abuse. Indeed, Leela had been ‘sold’ by her father to the local constabulary at the age of 13, and serially raped by them.

Over time, movingly, Leela becomes the author’s friend and confidante; through Leela and her circle, Faleiro is able to construct a picture of Bombay’s subculture of hirjas (she-males), prostitutes and gangland pimps. Inevitably, what Faleiro unearths is shocking. But, in spite of its grim subject matter, Beautiful Thing is leavened by passages of humour and by Leela’s own, coarse-tongued sassiness (‘You’re in a mood blacker than a Bengali’s arsehole’, she tells a customer, charmingly.)

Whatever the wretchedness of their past, bar dancers like Leela disdain to be associated with ‘Indian’ poverty and the nine million who are said to subsist in the Bombay slums. Even the poorest in the shack dumps off Mira Road, where Leela operates out of a bar called Night Lovers, look down their noses at those in the squatter colonies of the Kamatipura red light district. In Bombay, with its complex caste separations, a sense of hierarchy lies beneath all social interaction; Leela herself feels keenly the lack of social mobility available to her in the big city.

In the end, poverty makes criminals of everyone in Bombay, says Faleiro, and Leela is no exception. After the 2006 prohibition on dance bars, she finds herself roaming the streets unemployed. While dancing has not been outlawed in high-end luxury hotels such as the Taj, Leela knows she is of the wrong caste and colour for such finery. Instead she turns to prostitution. (Her mother, out of a similarly dire necessity, sets up as a brothel madame.)

We last see Leela alone and destitute in the predominantly Muslim slum settlement of Cheetah Camp, harried by the local mafia and by child beggars. Her dream is to escape across the Arabian Sea and work for a pimp in Dubai; there might be choice pickings there. Useless to describe the pathos and singular power of this book. Beautiful Thing is, quite simply, one of the finest books on Bombay ever written.

Comments