Like the Dombeys, Pitts, Amises et al, les Dumas are famously père et fils, but there was of course also a grand-père, Thomas-Alexandre, or ‘Alex’ the first, who was a wildly romantic figure, a gallant and tragic hero, and the defining influence on his son’s life and work.

In his memoirs, of which he devotes more than 200 pages to his father’s life, the author of The Count of Monte Cristo, (Dumas père) remembers how, one night in 1806, when he was not yet four, he was woken with news of his father’s death: ‘taken by God’. He asked where God lived: heaven. Soon afterwards his mother found him with one of his father’s guns. He explained that he was going to heaven, ‘to kill God, who killed Papa’.

A boyhood memory of reading that passage has inspired Tom Reiss, an American journalist, to write The Black Count. Reiss began by making an appointment with the custodian of the Dumas museum at Villers-Cotterêts in Picardy, but arrived to find that she had died, leaving the papers he wished to see in a safe, with no combination. A cash donation of €2,000 to the Alexandre Dumas Memorial Safe Fund persuaded the deputy mayor of Villers-Cotterêts to permit a locksmith to open the safe, and though the first of many biographies was published in 1797, Reiss assures us that his is the first to be based on Dumas’ own papers.

The son of an aristocratic rogue and a black slave, ‘Alex’ was born in 1762, on the French sugar colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti), where slaves were known as ‘pieces of India’. To fund his passage home to France, the rogue sold his lovers and children, but out of fondness for Thomas-Alexandre sold him only ‘conditionally, with the right of redemption’ — pawned him, in other words — and when he succeeded to a marquisate he redeemed the lad and sent him to school in Paris.

In 1786, more than six feet tall and already well trained in fencing and riding, he enlisted as a private in the Queen’s Dragoons, as ‘Dumas, Alexandre’ — the first record of that name. He soon distinguished himself, once fighting three duels in 24 hours, and was promoted to corporal. When the Revolution arrived he became a fervent republican, and the Revolution loved him back. ‘Americans’, as blacks were known, were given fullcitizenship, and Dumas was appointed first a lieutenant colonel of the Free Legion of Americans — the Black Legion — and then, at the age of 31, a brigadier general of the Army of the North.

In the Alps, after a bayonet charge across a glacier, Dumas took the apparently impregnable Mont Cenis from the Austrians (who called him die schwarze Teufel, the Black Devil), thereby opening up Italy; and for his single-handed defence of the bridge at Clausen, Napoleon called him ‘the Horatius Cocles of the Tyrol’. On his way back from the Egyptian expedition, Dumas put in at Taranto, which he assumed was still a French-backed republic but turned out to have been retaken by the Kingdom of Naples. He was imprisoned for two years, apparently poisoned, and lost the use of an eye and an ear.

The General returned to France, his health ruined, to find that Bonaparte, with whom he had fallen out in Egypt, had proclaimed himself emperor, and was in the process of reversing the Republic’s policies on racial equality. Denied further military appointment, or even the pay he was owed, he died in 1806, leaving his wife and son practically destitute.

Reiss’s history in interesting in some of its details, particularly concerning the Egyptian expedition — the Cairene clergy, for example, offered to acknowledge Napoleon as ruler of Egypt if the French army would convert to Islam, which Napoleon seriously considered, until it became clear that this would entail abstinence from wine and mass circumcision. But it tends to be both plodding and garbled, and the style is frankly villainous. Anything remotely unusual is ‘surreal’, and such statements as ‘the French would unleash storms that are still igniting conflict’ are depressingly typical.

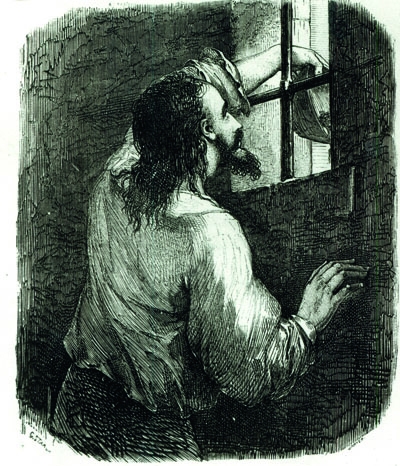

And despite the promise of his title, Reiss has little to say about Dumas’ great novel, beyond observing that he drew on his father’s account of his captivity ‘for the iconic scenes of human suffering in The Count of Monte Cristo’, and that Deodato Dolomieu, Professor of Natural History in Paris and briefly the General’s fellow prisoner at Taranto, was the model for Abbé Faria, the polymath who tunnels to Edmond Dantès’ cell by accident, educates him, and gives him the treasure map. The ‘real’ Count of Monte Cristo remains the one in the novel.

Comments