When, many years ago, I finished reading Cecil Woodham-Smith’s fine and tragic The Great Hunger, I swore never to read another book about the Irish famine of 1845-9. But they continue to be published, and they do not always agree. Tim Pat Coogan’s The Famine Plot: England’s Role in Ireland’s Greatest Tragedy, whose title says everything about the book, claims that ‘fully a quarter’ of Ireland’s population died of starvation or emigrated. John Kelly’s The Graves Are Walking puts the proportion at one third. There is a huge difference between one third and one quarter. Which is correct?

There is also much emotion. Coogan writes:

If ever one required an object lesson as to the validity of a saying I first heard in Vietnam — ‘when elephants fight it is the grass that gets trampled and the people are the grass’ — one need look no further than Ireland.

But if the analogy is to make any sense at all, who are the elephants? Again, Coogan quotes A.J.P. Taylor in one of his wilder moments, making the comparison with Belsen: ‘All Ireland was a Belsen.’ John Kelly cites the literary critic Terry Eagleton calling the famine ‘the greatest social disaster of 19th-century Europe — an event with something of the characteristics of a low-level nuclear attack’. Since no such low-level attack has ever taken place, how can it be used for purposes of comparison with a famine or anything else?

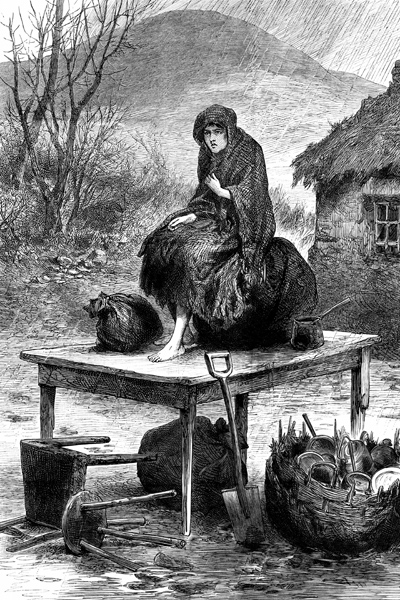

Fortunately the third of these books does not deal in such nonsense. Cork University Press’s Atlas of the Great Irish Famine is a sober and serious undertaking, and a great deal of thought, industry, ingenuity and money has gone into it. There are 700-odd pages, over 200 specially compiled maps as well as many drawings and photographs, some of which are beautiful as well as fascinating.

The atlas is cleverly put together and begins with an excellent account of the various modifications — and silences — of Irish (and English) historiography over the last 150 years. The large number of contemporary documents, many handwritten, give an extraordinarily vivid picture of the times.

There is a section on the literature the famine inspired, another on the art, a third on the music, with scores, and a fourth on the coverage in Celtic. A good deal of poetry is included. There is also extensive coverage of the emigration, especially, of course, to America, but also to Canada, Australia and elsewhere.

Foreign reactions are recorded too, notably in France, which contributed warmly to Irish relief, with Ireland responding generously during the Siege and Commune in Paris in 1870-1. It also contains curious facts: among the direct descendants of a famine emigrant to America was President Obama’s mother. This is a wonderful book, marred only by its enormous weight.

At this distance of time, and after successive waves of varying historiographies and emphasis, ranging from ‘an act of English genocide’ to ‘no one was to blame — much’, does anything remain to be said? Sir Robert Peel, prime minister during the early stages of the famine, was much more successful at handling it than his Whig successor, Lord John Russell, because he did the practical, obvious thing of importing cheap food and distributing it. Whereas the Whigs tended to see the famine as an opportunity to allow events to force through structural reforms in the Irish system. This was much the more painful alternative, and led to far higher death rates.

Probably the best of the various ugly solutions was government-assisted emigration. But this in itself was a confession of failure. It is a curious fact that Britain was much more successful at handling famine in India and Africa than in Ireland. This was because Ireland was not a colony: it was part of the United Kingdom and enjoyed parliamentary government. Parliament, where believers in laissez-faire economics were in a decisive majority, was one of the obstacles to a sensible famine policy, such as could easily be applied in Bengal or the Punjab.

The 19th-century English had a horror of Ireland because it was an example of the almost total failure of English statesmanship, the only one in the entire British empire where defeat and frustration were the results of 800 years of occupation. Gladstone, despite his increasing preoccupation with Irish problems, went there only once. Disraeli never. Queen Victoria spent three months every year in Scotland but she visited Ireland only twice in her life, and then briefly.

It was difficult to get the English even to read about the place. Though Trollope loved Ireland, and writing about it, his publisher forbade him ‘any more Irish novels’. Dickens only went there for three brief reading tours towards the end of his life. Thackeray visited and wrote a short book — one of his best in fact, The Irish Sketchbook — but that was in 1843, before the famine. Carlyle went there too, but was deeply pessimistic, and wrote: ‘Ireland is a starved rat that crosses the path of an elephant. What is that elephant to do? Squelch it, by heaven! Squelch it!’

If Ireland had been an independent, self-governing country, could the famine have occurred? There are too many ‘ifs’ for this question to be answered. Recent history is not encouraging. Though independent Ireland appeared to flourish under the European Union, and carry the name of the Celtic Tiger, it was also returning to its 18th-century habit of corruption. And when the 2008 bubble burst and the tiger was seen to be only a tigerskin, the corruption moved to the forefront.

Ireland is once again a deeply stricken country — and this time the English can’t be blamed.

Comments