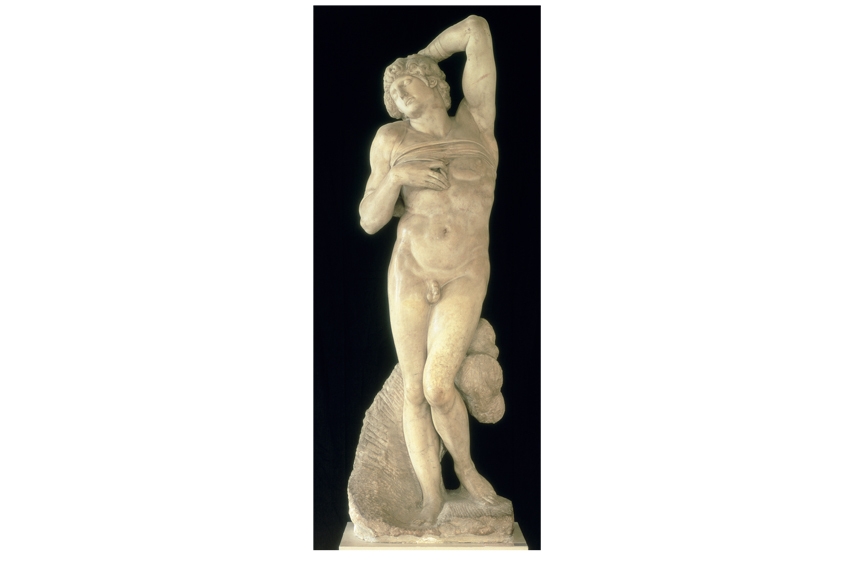

In the summer of 1520, Michelangelo Buonarotti wrote a letter of recommendation on behalf of his protégé, the painter Sebastiano del Piombo, to Cardinal Bibbiena, an influential figure at the court of Pope Leo X. The testimonial carried some weight, for Michelangelo was by now Italy’s most admired sculptor, with what are nowadays called ‘signature achievements’ such as the David, the Pietà and the Dying Slave to his credit. Seven years earlier, what is more, he had completed the magisterial decoration of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, among the most ambitious projects in the history of painting, for Pope Julius II.

It comes as something of a surprise, therefore, to find the artist referring to himself, in this same letter, as a man of no significance, prematurely aged, impoverished and mad. Even if the Cardinal must think of granting his request merely in terms of a favour thrown away, protests Michelangelo, some pleasure may be found in favouring madmen, like that of changing to a diet of onions following a surfeit of capons.

Did Michelangelo believe any of this? Probably not. Aged 46, he was hardly, even by the standards of his time, a Methusaleh, and would survive, without serious physiological setbacks, for another four decades. As for money, though instinctively careful over his accounting, he never faced serious poverty. A ne’er-do-well family, headed by his Micawberish father Lodovico, knew it could always rely on his support as a master artificer in the service of Italy’s most illustrious potentates.

The image presented to us in this, the first instalment of Michael Hirst’s two-volume biography, is one which confirms the impression created by an initial encounter with the artist’s works, from the Sistine ‘Last Judgment’ to the smallest preparatory sketch, that of a man who never looked over his shoulder. No wonder Pope Leo, after receiving the letter mentioned earlier, referred to Michelangelo as ‘terrible’.bastiano del Piombo later warned him that though ‘His Holiness talks of you like a brother, with tears in his eyes, you frighten everybody, even popes.’

Intractable, Hirst calls him, and intractability was a keynote of his career. A resolute digging-in of heels characterised everything, from his cheese-paring negotiations over free accommodation while labouring on the Sistine Chapel to his deliberate dawdling among the Carrara marble quarries during the autumn of 1516, well aware that his Medici patrons, led by Pope Leo, were desperate for him to start work on a suitably dignified facade for their Florentine family church of San Lorenzo.

Unaffected by any lingering doubt as to the astonishing range of his talents, Michelangelo’s acknowledgment of his artistic contemporaries oscillated between lofty indifference and open resentment. The choice, by Cardinal Giulio de’Medici, of the egregious Baccio Bandinelli to create a companion sculpture for the David roused his competitive fury, but a more intense hatred was reserved for Raphael, whose dangerous versatility needed careful watching. Fretfulness of whatever kind, over everything from patrons and pay-masters to those bouts of sickness, and stress induced by grand projects like the New Sacristy at San Lorenzo, seems always to have sharpened his appetite for living.

There is material here for a tremendous biography, and Michael Hirst, as the most eminent living authority on the artist, is ideally placed to write it. Sadly Michelangelo: The Achievement of Fame mostly fails the challenges posed by its subject. In a work of this kind, apparently aimed at the general reader as much as at the writer’s academic peers, it is not enough to focus, as Hirst seems content to do, on scholarly analysis and comparison of documentary sources. There has to be some broader engagement with those social, historical and cultural contexts, each of them so rewarding in its wealth of detail, surrounding the fascinatingly restless and uncertain Renaissance phase in which Michelangelo sprang to the world’s notice.

As it is, the book remains curiously reticent on these, as on the subject of his poetry, some of its period’s most arresting, mentioned here en passant but never adequately examined. We are given no sense of how his style developed and the works themselves, whose genesis and completion ought to furnish suitable moments of reflective stasis in the narrative, are evoked as little more than chronological catalogue entries in the logbook of an accomplished artisan. Most disappointing of all is Hirst’s own reluctance to communicate anything, whatever of the exhilaration we must assume he feels in confronting these genuinely astounding achievements.

Is it too much to ask him to break, for a moment, with the tight-lipped convention of modern art-historical writing which forbids the expert to reveal himself as anything quite so vulgar as an informed enthusiast? What does Hirst actually love about Michelangelo? Let us hope he seizes the opportunity, in his second volume, to tell us.

Comments