‘What porridge had John Keats?’ Browning offers this as the crass sort of question that stupid people ask. But in fact the first person to answer it would have been John Keats himself. He loved to talk about food, good and bad. He writes to his dying brother Tom from Kirkcudbright that ‘we dined yesterday on dirty bacon, dirtier eggs and dirtiest potatoes with a slice of salmon’. As Keats and his Hampstead friend Charles Brown tramped round Loch Fyne, he complained that all they had to live off were eggs, oatcake and whisky:

I lean rather languishingly on a rock, and long for some famous beauty to get down from her Palfrey in passing; approach me with her saddle bags — and give me a dozen or two capital roast beef sandwiches.

He bathed in the loch, at Cairndow, ‘quite pat and fresh’, until a gadfly bit him. The inn at Cairndow is still there. So is the Burford Bridge Inn under Box Hill where he finished ‘Endymion’. You can still follow the path through Winchester which he describes taking while thinking of the ‘Ode to Autumn’.

No other dead poet is, I think, quite as intensely present to us still, somehow in the flesh. In his review of Keats’s first published volume, Leigh Hunt fastened on the essential thing about him, that he had ‘a strong sense of what really exists and occurs’. In this beguiling new biography, Nicholas Roe, the foremost Keatsian around, seeks to wipe away any lingering image of a sickly moony dreamer and to show us the ‘edgy, streetwise’ livewire who rejoiced in the material world for all of the short time he was in it.

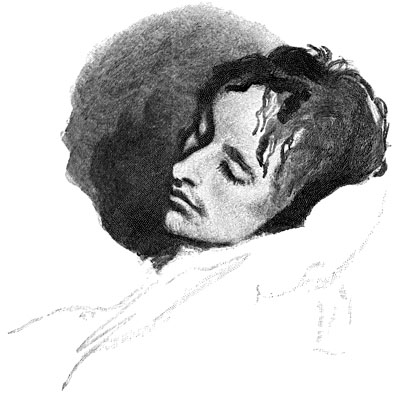

He was only five foot and three-quarters of an inch, but he always filled the room. When he recited poetry — his own or anybody’s — he ‘hoisted himself up and looked burly and dominant’. Hunt remembered his appearance when they first met: very broad-shouldered for his size, with a face that was ‘delicately alive’, something pugnacious about the mouth, and large, dark, glowing eyes. Which is just how he looks in Joseph Severn’s picture of him listening to the nightingales, painted a quarter of a century after his death. Nobody forgot Keats or what it was like to be with him.

To his friends, Keats sometimes signed himself ‘Junkets’, and when his restless spirit sent him off on a new excursion, the dis-

appointed cry would go up, ‘What’s become of Junkets?’ At a noisy supper party given by the man who supplied the scalpels he used as a medical student, he and his friends argued about the correct derivation of the vulgar word for what polite society probably now calls a ‘Naomi’. That evening he won ten shillings and sixpence from cutting cards for half-guineas, high stakes for struggling City clerks. Such episodes of ‘delicious diligent indolence’ (characteristic of all the Keatses, according to their fussy trustee Mr Abbey) remind one of Bertie Wooster spending a restful afternoon at the Drones, throwing cards into a top-hat with some of the better element.

Yet his energies were prodigious, physically and mentally. In Scotland, he and Brown walked 20 or 30 miles a day. He had translated the whole of the Aeneid by the time he was 15. His collected poems, mostly written over only five years, between the ‘Imitation of Spenser’ in 1814 and the ‘Ode to Autumn’ in 1819, fill 437 pages of the old Oxford edition. He could compose with remarkable rapidity. A cricket chirped in the hearth of Leigh Hunt’s home in the Vale of Health, and Hunt challenged him to write a sonnet about it inside 15 minutes. Keats met the challenge with the sonnet that begins ‘The poetry of earth is never dead’.

There have been many fine biographies of Keats since the war, notably by Aileen Ward, Robert Gittings and Andrew Motion. But none, I think, conveys quite so well as this one the sense of Keats as a poet of the London suburbs. Roe reconstructs beautifully the milieu from which he and his friends all came, on the northern edge of the City where they had their day jobs and dreamed of fame.

Keats himself was probably born at the Swan and Hoop at Moorgate, the inn which his father Thomas had taken over from his prosperous father-in-law, John Jennings, and turned into Keats’s Livery Stables. Thomas Keats had been brought up in the workhouse at Lower Bockhampton, Hardy country, and had come to town and married the boss’s daughter Frances. Their three young sons were sent up to Clarke’s Academy at Enfield, a school for Dissenters which had a far wider and more up-to-date curriculum than Harrow, where Frances had thought of sending them.

Roe describes it, with justice, as ‘the most extraordinary school in the country’. The idea that Keats, because of his modest background, was ‘under-educated’ could not be further from the truth. But his happy start in life came to an abrupt end when in April 1804 Thomas Keats fell from his horse to the pavement outside Bunhill Fields and smashed his skull only a few yards from home.

From this fatal accident, all Keats’s troubles flowed. The substantial legacy from his grandfather was tied up in Chancery where it remained for years (his sister Fanny was still trying to extricate herself from the muddle in the 1880s). Only two months later, Frances remarried, to a no-good called William Rawlings, whom she deserted almost as swiftly (Roe deduces fairly enough that she was having an affair with Rawlings before she was widowed). Frances was already addicted to opium and brandy, and the children were shuffled off to their grandmother’s in Edmonton and never lived with their mother again until she came up to Edmonton to die.

John nursed her, prepared her meals, read her novels and sat up with her at night, listening to the rattle of her breathing. Though she had more or less deserted them, his devotion was total, as it was to be to his brother Tom when he was dying of consumption. Looking back on his life, Keats was to reflect that he had ‘never known any unalloy’d happiness for many days together: the death or sickness of some one has always spoilt my hours.’

Roe takes trouble too to show how diligent Keats was in pursuing his medical training, first as apprentice to a disagreeable Edmonton surgeon, then at Guy’s Hospital. When Keats complained that Newton had destroyed the magic of the rainbow, he was doing so not as a fretful dilettante but as someone with as rigorous a scientific training as was then available.

Nor was he in the least soppy about nature. Thirty years before Tennyson’s outburst against ‘Nature red in tooth and claw’, Keats lamented the process of ‘eternal fierce destruction’. Beneath the beautiful surface of the sea, ‘the greater on the less feeds evermore’, and in Highgate Woods while he was gathering periwinkles and wild strawberries, the hawk was pouncing on the smaller birds, and the robin was ‘ravening a worm.’

Roe does not spend much time on Keats’s views of politics and religion, merely labelling them as unorthodox. Certainly he never ceased to revere the republican heroes of the Civil War or to be hostile to the ‘pious frauds’ of the Established Church. In his ‘Sonnet written in Disgust of Vulgar Superstition’, Keats says how much he hates the gloomy church bells which would have made him

feel a damp —

A chill as from a tomb, did I not know

That they are dying like an outburnt lamp.

Yet his description of life as ‘a vale of soul-making’ and his insistence ‘how necessary a world of Pains and Troubles is to school an intelligence and make it a soul’ would certainly appeal to Christians then and now. When he was dying, Severn read aloud to him from Don Quixote and the novels of Maria Edgeworth, but Keats asked instead for Plato, The Pilgrim’s Progress and Jeremy Taylor’s Holy Living and Holy Dying, not the likely choices of a committed atheist such as Shelley.

In his eagerness to show us the streetwise Keats, Roe sometimes slides past the more serious resonances. Especially destructive is, I think, Roe’s itch to return to two themes which are to be found in other accounts of Keats’s life but which do seem to be overplayed here. These are a) that Keats was dosed to the gills with laudanum when he wrote his last great odes, and b) that from 1816 onwards he was taking mercury, no longer to cure his gonorrhea but to fend off his emerging syphilis.

This may well tickle up a few headlines (indeed it already has), but the evidence is shaky. Dr Sawrey could well have gone on prescribing mercury as a precaution against a return of the clap or as a remedy against the ulcerated throat, a first symptom of the tuberculosis taking hold. There really isn’t much licence for Roe to assert that ‘some aspects of his distorted behaviour and perceptions towards the end of his life may be attributed to an awareness of this “secret core of disease” rather than to tuberculosis.’ Even in full health, Keats was, well, mercurial, and TB is classically depicted, e.g. by Thomas Mann, as inclined to bring on manic behaviour.

The argument about the laudanum is reductive too. Yes, of course Keats took laudanum. When he was nursing Tom, they both did when they couldn’t sleep. So did thousands of other people throughout the 19th century, as a painkiller or just to get high. But does this really make the ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ into ‘one of the greatest re-creations of a drug-inspired dream-vision in English literature’? The poet tells us explicitly that neither the ‘dull opiate emptied to the lees’ nor the beaker of blushful Hippocrene is assisting the flight of his fancy. To insist that the laudanum was a necessary stimulant is to insult that intelligence, which other great critics such as T.S.Eliot have regarded as the keenest of any poet.

John Keats had enough trouble in his lifetime with his first publishers, who said that they regretted ever taking on his verses and that ‘we have in many cases offered to take the book back rather than be annoyed with the ridicule which has, time after time, been showered upon it’. He could not help being wounded too by the gibes of Blackwood’s Magazine, where the venomous John Lockhart under the pseudonym of ‘Z’ declared that his poems were ‘drivelling idiocy’ and that this ‘wavering apprentice’ was no better than a farm servant or footman with ideas above his station. This kind of snobbish abuse persisted long after Keats’s death. In patting him on the head for the ‘luxuriance’ of his verse, W.B.Yeats described him in 1915 as ‘poor, ailing and ignorant … the coarse-bred son of a livery stable keeper’.

Besides being accused of being underbred and undersized, Keats now has to put up with being accused of being under the influence. Reductive too, I think, is Roe’s insistence that any description of death and suffering in Keats’s verse must be drawn directly from the poet’s own family life, as though he couldn’t make it up for himself.

Yet all has to be forgiven when we come to Roe’s description of Keats’s last days, which it is impossible to read without coming close to tears. His last letters to Fanny Brawne remain as heartbreaking as ever. When they were first published, Fanny was denounced as a heartless flirt by the poet’s more hysterical admirers. It was only when her own letters to Keats’ sister Fanny were published that readers slowly came to understand how warm and touching and loyal she was.

There is none of this after-history in Roe’s book. He ends rather abruptly, almost as though he is too moved to carry on, with Keats being buried in the English cemetery in Rome under the epitaph he had requested of Severn: ‘Here lies one whose name is writ in water.’ Which is, I think, a pity. We need to know how life moved on, how Fanny mourned him for years, then married and had two children; how Severn lived on in Rome until 1879, becoming a local celebrity not for his painting but for being the only friend who had stayed with Keats to the end.

And we need too to survey the later history of Keats’s reputation, to see how the sad romance of his life made him a hero to the Victorians, and how he fell out of favour among a generation which preferred battery acid to honeydew. The reaction against luxuriance has continued. A distinguished poet said to me not so long ago: ‘I can’t see how anyone could think Keats is any good.’

Re-reading Keats, though, I am still inclined to echo the judgment of that acute and implacable critic Samuel Beckett:

I like him the best of them all, because he doesn’t beat his fists on the table. I like that awful sweetness and soft damp green richness, and weariness: ‘Take into the air my quiet breath’.

There is something irresistible too in the way Keats suddenly breaks out of the mossy glooms and speaks to us with a high clarity which makes me shiver, for example in Endymion:

But this is human life: the war, the deeds,

The disappointment, the anxiety,

Imagination’s struggles, far and nigh,

All human; bearing in themselves this good,

That they are still the air, the subtle food,

To make us feel existence, and to show

How quiet death is.

And there is always an instinctive tenderness in his poetry, and in his letters too, which you won’t find much in chilly Wordsworth or sardonic Byron. I cannot stop thinking of the few lines he scribbled down right at the end, just after he had become secretly engaged to Fanny:

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming

nights

That thou wouldst wish thine own heart dry

of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d — see here

it is —

I hold it towards you.

Comments