‘I cannot say there is no vanity in making this funeral oration of myself, but I hope it is not a misplaced one,’ wrote David Hume on the eve of his death in 1776, under the title, ‘My Own Life’. It is with this same title that, accepting the inevitable progression of metastatic cancer in his liver at the age of 81, Oliver Sacks paid tribute to his favourite philosopher. Like Hume, the charge of vanity was not unfamiliar to Sacks when writing about his achievements and the shapes of his inner life. In a way rare for a doctor, Sacks was prepared to admit that vanity is part of the medical endeavour: a restless pursuit to know the goings-on of your mind, to understand your heart, your lungs and your legs, to look again and again and again.

Sacks made peace with vanity in 1984 when he wrote a case history of himself. In A Leg to Stand On, he documents a mountaineering incident which led him to break the cardinal rule of being a doctor in the public’s eyes: he got sick. Given that Sacks writes so well in the role of patient, it is almost disappointing that Gratitude is in no way an illness narrative.

The quartet of essays, all of which appeared in the New York Times over the two years before he died in August 2015, scarcely mention the cancer treatment he received over the previous decade. There is no railing against infirmity, no pain, no confided suffering. Sacks’s final insights are comfortably wise: ‘living a good and worthwhile life — achieving a sense of peace within oneself’ — words which bind together a biography so diverse it is impossible to summarise.

Instead, Gratitude tells about the improbability of Sacks becoming a doctor. As a boy he was fascinated by the world of the physical sciences ‘where there is no life, but also no death’. He found himself studying medicine at Oxford because both of his parents were clinicians. University was followed by disillusionment and depression, self-experimentation, near-suicidal amphetamine addiction, a period living among a community of weightlifters on Muscle Beach in California, struggles with his ‘agonising’ shyness and extreme immoderation. These experiences were to make him a very different medic to his surgeon mother, who became distanced from her son after brutally condemning his sexuality.

Three people are mentioned more than once in Gratitude’s 45 pages: Hume, Francis Crick and W.H. Auden, the last two of whom were Sacks’s friends. The philosopher, the scientist and the poet: a combination which awakened medicine for Sacks as a richly hybrid discipline and enabled him to set down his patients’ stories. But such sensitivity to the plight of others was not always convenient. ‘In a sense, I was in love with my patients,’ he once said.

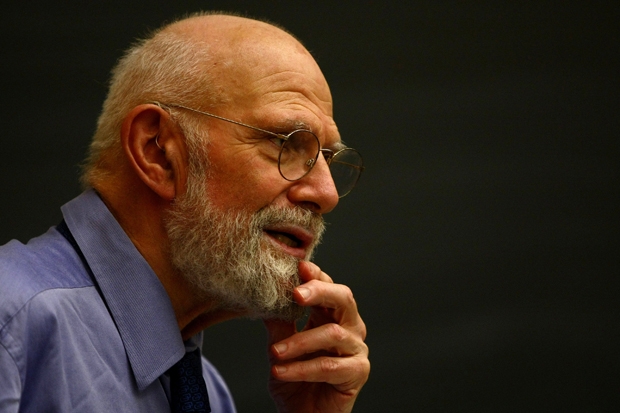

Gratitude’s navy cloth cover and embossed gold lettering are grandiose. The volume’s first essay, renamed ‘Mercury’, was printed originally under the more playful title, ‘The Joy of Old Age. (No Kidding)’, a revision which hints at a regrettable smoothing of Sacks’s eccentric legacy. Luckily this is undone by photographs accompanying the text, taken by Sacks’s lover, Billy Hayes, which show us Oliver at his desk, smiling to himself as he writes by hand on yellow lined paper. Sacks sitting under a tropical palm, holding a magnifying glass and a defiant walking cane, wearing a leather jacket and New Balance trainers. Swimming in a cap and goggles under a cloudy sky. Two pairs of glasses resting on pages of marginalia and crossings-out. These images reunite Sacks with the message he advocated: ‘the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being is to be a unique individual’.

Physicians tend not to spend much time thinking about their own uniqueness. But if you ask medical students the kind of doctor they would like to be, or ask patients about the kind of doctor they would like to see, the world’s most famous neurologist, who made a career out of thinking about such things, stands firmly first. Gratitude is a timely reminder that Oliver Sacks triumphed when he did what doctors are encouraged not to do.

Comments