Four years ago Roy Strong – one-time director of both the National Portrait Gallery (1967-73) and the V&A (1973-87) – published The Elizabethan Image: An Introduction to English Portraiture, 1558-1603, in which he returned, after more than a 30-year hiatus, to the subject with which he first made his name: the imagery of Queen Elizabeth I and her court. Now 88, the indefatigable Strong has produced a follow-up volume charting the fate of portraiture (and painting and the visual image more generally) at the courts of Elizabeth’s Stuart successors, James I and Charles I.

Charles I would travel by barge to Van Dyck’s studio to pass the time with him and watch him paint

The format of – and thinking behind – The Stuart Image is the same as in the previous book. Strong has revisited his own landmark research from the 1960s to the 1980s and knitted it together with the findings of subsequent generations of art historians to create an accessible, jargon-free introductory text for the general reader. Most scholars of the Stuart court and its imagery have tended to tackle the subject via the leading painters of the day: Rubens, Van Dyck and so forth. Strong, by contrast, takes the leading patrons of the day – the Stuart kings, their consorts, and their courtiers – as his point of departure. It is an approach which – coupled with his keen eye for the amusing and telling anecdote – makes for a narrative that zips along.

We meet courtier-collectors, such as James Hamilton, 3rd Marquess of Hamilton, who acquired more than 600 Venetian and north Italian pictures in a short space of time in the 1630s. In these endeavours he was assisted by Basil Feilding, 2nd Earl of Denbigh, the English ambassador to Venice, whom he pressed into service as his agent. Hamilton was, as Strong notes drily, ‘what we would now categorise as a shopaholic’. His letters to Feilding are filled with enthusiastic declarations of his love of paintings (‘I ame much in loofe with pictures’), coupled with concerns about his inability to stop spending money on them: ‘I might be so much bewitched with those intysing things.’

And we encounter Charles I – arguably the greatest patron of the age – travelling along the Thames by barge to visit Van Dyck in his studio in Blackfriars, where, according to Gian Pietro Bellori (a Vasari of the 17th century), the king ‘took pleasure in watching him paint and passing the time with him’. No wonder: Van Dyck’s studio was a hive of activity, albeit of a very precise and well-ordered variety. Sitters were booked in back-to-back, each for no more than an hour at a time, with the result that Van Dyck (in the words of Roger de Piles, writing in the early 18th century) ‘work’d on several pictures the same day, with extraordinary expedition’. Strong calculates that Van Dyck – no doubt helped by what must have been a sizeable number of assistants in his Blackfriars studio – produced at least one finished portrait every fortnight from 1632 to 1641.

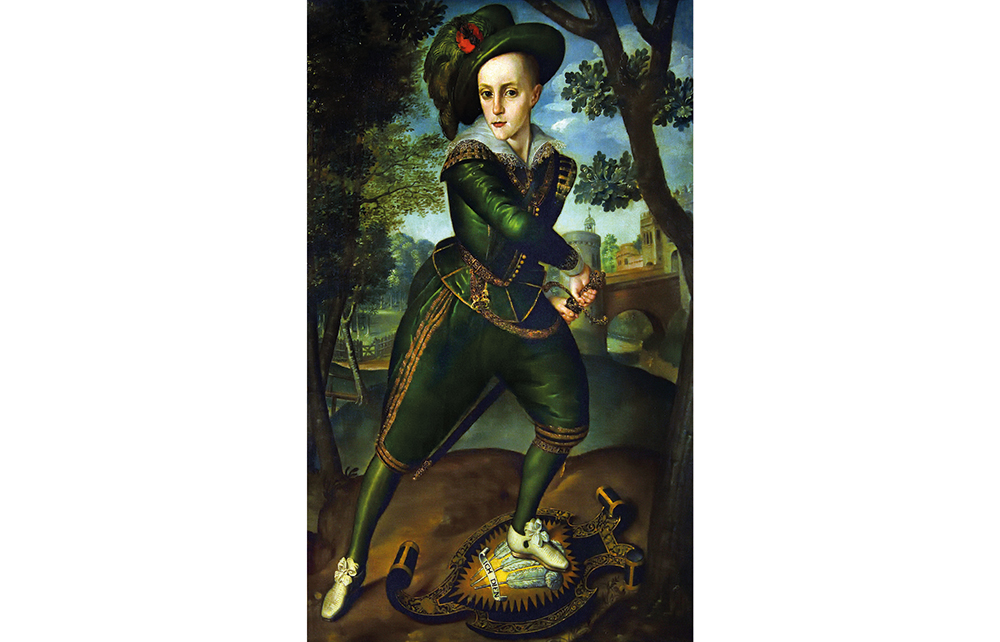

Woven throughout is a consideration of the evolving status of painting and the artist in England. By the 1620s, writes Strong, painting ‘had made the ascent from a mechanical to a liberal art’. It was now possible for someone like Sir Nathaniel Bacon – the youngest son of a baronet and the grandson of Sir Nicholas Bacon, Elizabeth I’s Lord Keeper of the Great Seal – to be a painter, albeit an amateur one, without fear of social stigma. Increasingly, conduct books decreed that gentlemen (and aspiring gentlemen) should be taught draughtsmanship and painting. Henry Peacham’s Compleat Gentleman (1624) went so far as to argue that such skills were essential both for the soldier knight (to record enemy fortifications) and for the great landowner (to survey and maintain his lands).

Painting and portraiture are Strong’s primary focus in The Stuart Image. But he also succeeds – with the help of more than 100, mainly colour, illustrations – in vividly evoking the period’s architecture and court masques, the latter a subject whose serious study he pioneered with landmark exhibitions such as The King’s Arcadia: Inigo Jones and the Stuart Court, mounted in 1973 at the (then newly restored) Banqueting House in Whitehall to mark the 400th anniversary of Jones’s birth.

Fans of Strong’s original publications, and of The Elizabethan Image, will find this latest book a treasure trove. Elegantly written, it is also an exceptionally handsome volume, the typeface, ornaments and general layout of which all pay homage to – and in some cases are directly copied from – works produced by the book printers of early Stuart London.

Comments