The IFS has given the coalition’s opponents powder for their muskets, only it’s a little damp. The

IFS’ analysis is drawn exclusively from straight tax and spend figures;

it does not account for the future financial benefits brought by structural public service reform – so Gove’s and IDS’ reforms, both of which aim to alleviate poverty, have not

been evaluated. Matthew Sinclair explains why

this means the IFS has exaggerated the severity of Osborne’s Budget:

The IFS has given the coalition’s opponents powder for their muskets, only it’s a little damp. The

IFS’ analysis is drawn exclusively from straight tax and spend figures;

it does not account for the future financial benefits brought by structural public service reform – so Gove’s and IDS’ reforms, both of which aim to alleviate poverty, have not

been evaluated. Matthew Sinclair explains why

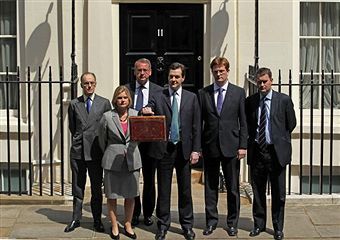

this means the IFS has exaggerated the severity of Osborne’s Budget:

‘Suppose you invented a policy, some kind of economic miracle, which doubled the incomes of the poorest ten per cent of families without the Government spending a pound. That would reduce benefit spending. It would also increase tax revenues from the poorest. The same method that the IFS are using in their reports would show the effects of that policy as horribly regressive, cutting spending on the poor and shifting the fiscal scales against them. Of course that is an extreme and artificial example. But it shows the big problem with the IFS analysis, which essentially assumes that the fortunes of the poor add up to the amount of Government money spent on them.’

The IFS is the keenest lookout for the Treasury’s love of small print. Sometimes, though, even oracles like Robert Chote see things that don’t exist.

But the IFS’ oversight raises an important political issue, touched on by Bruce Anderson in his FT column today. The government is cutting public spending and re-imagining the role of the state – more for less is its creed. It seeks a radical narrative which rejects the Brownite axiom that spending is the sole indicator of healthy public services. It’s yet to find one. No one, not even the IFS, has adopted the government’s new language and methodology because the government is yet to convey it clearly. Today’s mini-crisis is partly of its own making, pitching arguments in terms of ‘fairness’ and ‘progressive’ is a continuation of the terms of New Labour’s economic debate.

Comments