Drawing penises and making vulvas out of Play-Doh might not be the reply most parents expect when they pose the question, ‘What did you get up to at school today?’ But with even the youngest children now encountering explicit content and bizarre teaching methods in mandatory sex education classes, it is an answer more might come to hear.

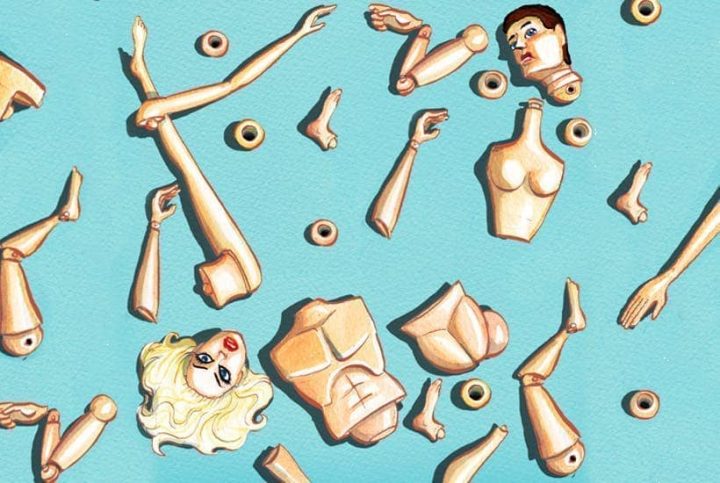

Masturbation, oral sex, anal sex, fisting, rough sex, gender queer, polyamory. When the school curriculum can be confused with the dropdown menu of a pornography website, something has gone wrong. But it is not just highly sexualised content that is concerning parents, they are worried about ideologically-driven and scientifically-inaccurate lessons in gender identity, too.

Children are being taught that people have a gender identity distinct from their sex and that – despite what their biology teachers may have said – sex itself is just a label randomly assigned at birth. This allows pupils to be introduced to dozens of gender identities: from non-binary and agender, to demigirl and boi. Lessons reiterate the importance of respecting someone’s gender identity, including their preferred pronouns.

Progressive posturing about identity and a liberal approach to validating sexual practices has won out over safeguarding children

Between pictures of penises, ‘queer’ vocabulary lists and discussions about sex toys, it is hardly surprising parents have been raising the alarm. As a result, wince-inducing press coverage has detailed the graphic lessons to which children are being subjected. The New Social Covenant Unit has compiled a dossier of evidence setting out the content of so-called ‘sex positive’ relationships and sex education classes. Activities involve children ‘stepping away from heteronormative and monogamy-based assumptions’ in order to appreciate that ‘there are a variety of sexual preferences and practices – we’re all a little different’.

Following an intervention from Miriam Cates and 50 other Conservative MPs, Rishi Sunak has now announced an urgent review into ‘age inappropriate’ sex education. Good. Shock at what children are being taught may now be registering in the Houses of Parliament. But Conservatives need to acknowledge that many of the problems with relationships and sex education have arisen on their watch – and ‘age inappropriateness’ barely hints at what needs to change.

Sex education migrated out of biology labs decades ago. First introduced as a discrete subject in 1976, it carried a broader and more politicised remit than straightforward lessons in reproduction from the get-go. Back then, classes focused on teaching teenagers how to avoid getting pregnant or catching a sexually transmitted infection. The focus on contraception and abortion, rather than abstinence, already hinted at a permissiveness missing from biology lessons. But as most parents were on board with their teenagers not becoming pregnant, and as those who had concerns were able to withdraw their children from classes, things quietly carried on for the best part of three decades.

Towards the end of the 1990s, there was a growing clamour for Clause 28, which outlawed the promotion of homosexuality in schools, to be repealed. Campaigners wanted sex education to be set within the context of healthy relationships rather than just physical health. They were successful and new guidance issued in 2000 saw relationships formally coupled to sex education for the first time. Although consent and emotionally safe relationships were key features of the new curriculum, the dropping of Clause 28 left teachers free to cover not just sex but sexuality and a far wider range of sexual practices than previously.

The expansion of sex education into the area of relationships further complicated what for many teachers was already an awkward subject to have to teach. As a result, they readily gave ground to activist teachers who sought to carve out a niche role for themselves within schools. Alongside this, professional ‘sex educators’ began to emerge, selling their services to schools confused about how to meet the new guidance.

Until a few years ago, the only real concerns voiced by politicians and campaigners were that sex education did not go far enough and that parents were able to withdraw their children from classes. Both were answered by new statutory guidance introduced in 2019 which came into effect in 2021.

Backed by Theresa May and implemented under Boris Johnson’s premiership, the new curriculum was influenced by groups like Stonewall as well as international organisations such as the United Nations Children’s Fund and UNESCO. Its driving principle is to help children discover and celebrate their gender identity and sexuality. This is less about education and more about socialising children not to assume that cis-gendered people, heterosexual relationships or the traditional family are, in any way, considered ‘normal’.

Three things have consistently occurred in parallel: the expansion and over-complication of sex education has paved the way for activist teachers and politically motivated campaigning organisations to enter the classroom before, ultimately, their ideas have been enshrined in law. At each turn, progressive posturing about identity and a liberal approach to validating every conceivable sexual practice has won out over safeguarding children.

Indeed, we need only look to the promotion of secrecy to know that this is the case. Once a child protection red flag, now secrecy is all the rage in schools. Parents report being refused requests to view the resources and lesson plans that are used in their children’s relationships and sex education classes. Companies argue copyright but the suspicion is they do not want their practices to be subject to the scrutiny of parents or even other teachers. Secrecy again comes into play when schools allow children to socially transition – changing their name, pronouns and uniform – without ever informing their parents.

The government’s review into sex education cannot come soon enough. But for our children’s sake, this has to be about more than kicking out a few activists who have gone too far. Schools need reminding about what they should teach and – more importantly – what they should not. Some things, like masturbation, really can be left to youngsters to work out for themselves. And while schools clearly have a role to play in teaching the biology of sexed bodies and sexual reproduction, loving relationships can safely be left to parents to demonstrate.

Comments