One hundred years ago an 11-year-old boy called Georges Simenon was getting accustomed to the presence of the German army in Liège. Together with his mother and his younger brother he had been forced to hide in the cellar of their terraced house on the island of Outremeuse to avoid the firing squads. The Belgian fortress outside the city had resisted for longer than expected and had inflicted casualties on the invading army. The Uhlan lancers were so angry that 200 of the Simenons’ neighbours were lined up and shot. Once Belgian resistance had ended, the occupation of Liège became a quieter affair. For a while Madame Simenon even took in German soldiers as lodgers. Years later Georges recalled his youthful surprise at the number of German officers who wore corsets.

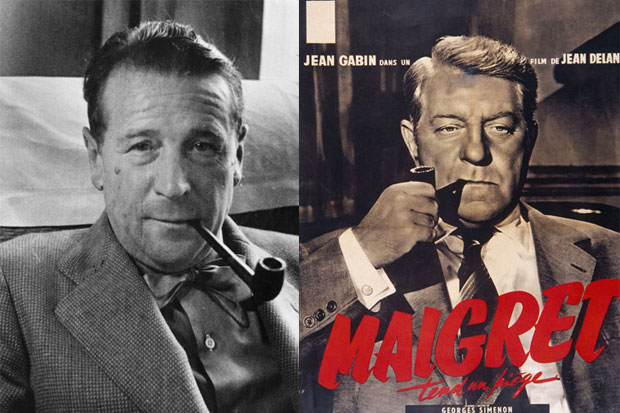

The name of Simenon will always be associated with his most celebrated creation — the pipe-smoking, hard-drinking Parisian detective Inspector Jules Maigret, and by the end of this year Penguin Classics will have republished the first 14 Maigret titles written between 1931 and 1932, as well as two of the 117 romans durs, the ‘straight’ or ‘dark’ novels that Simenon himself considered to be his finest work. This is welcome news, particularly since Penguin has commissioned new translations. Considering that the existing translations of Simenon include work by Antonia White, Moura Budberg, Nigel Ryan, Paul Auster, Robert Baldick, Julian McLaren-Ross, Isabel Quigley and Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, it will be interesting to see how the new versions compare.

Perhaps because of Maigret, Simenon is still frequently described as French. He himself once invented a family connection with an imaginary Napoleonic soldier who had apparently limped into the city on the retreat from Moscow. In fact he was born into a solidly rooted Belgian family, part Walloon and part Flemish. He never identified a family conflict in those terms, but he made a very clear distinction between the French-speaking Simenons, exemplified by his father, Désiré, who he depicted as an upright, bold, straightforward man, and his mother Henriette Brull, whom he described as one of ‘a tormented race’. Simenon’s father died when Georges was still a young man; Henriette lived into old age and seems to have dominated his emotional life. He stopped writing novels in 1972, just over a year after his mother’s death.

The division in the novelist’s family background can be traced in his work. Simenon did not write Maigret stories just to keep the pot warm; the policeman who solved his cases by understanding and frequently sympathising with his quarry was presented as the model for the way in which a good man should live his life. Maigret’s motto was comprendre et ne pas juger (‘Understand, don’t condemn’). The romans durs, on the other hand, depict a very different world — one in which justice plays little part and men and women have to learn how to survive without it. It is also a world that to some extent reflected the way in which the novelist actually lived his life.

Simenon’s writing career had started in 1923, soon after his arrival in Paris as a 19-year-old aspirant journalist. By the time Maigret was born, Simenon had abandoned journalism and was making a handsome living as ‘Georges Sim’, author of pulp fiction; he once published a personal record of 44 titles in one year.

The Maigret stories were the first Simenon published under his own name. He launched the series with a fancy-dress party in a Montparnasse nightclub just round the corner from the celebrated Brasserie La Coupole. Those invited had to be finger-printed at the nightclub door, a precaution which did not stop about 800 gatecrashers from joining the 400 guests. Like other best-selling novelists, Simenon, then aged 28, was already a master of self-publicity. But he was also a notoriously fast writer. Exhibiting both skills he once labelled one of his books ‘the first novel by Georges Simenon for eight days’.

The two strands of Simenon’s imagination come together in one of the early Maigret titles, A Man’s Head, just republished in a new translation by David Coward. The story is set in Paris, in the district of Montparnasse in the 1930s. Much of the action takes place in the bar of La Coupole. Maigret is pursuing a quarry who torments him, Radek, a brilliant young medical student. In France the penalty for murder is death; the guillotine is set up in the street, with the execution being carried out in public. Maigret recognises Radek as the killer, but has to work out how to connect him with the crime.

Simenon wrote the story in a hotel room on the Left Bank at a time when one of his boyhood friends, who had become a gigolo, was plotting a murder on the other side of the city. Simenon once said that he too could easily have become a professional criminal, like several of his friends, and that the crimes he wrote about were the ones he would have committed if he had not escaped that fate.

The series eventually reached 76 titles, and the last novel Simenon ever wrote was a ‘Maigret’. It concerns a woman of 45 who decides to bump off both her husband — a lawyer — and her lover — a failed barman. By that time Simenon was waging a monumental battle with his second wife, Denyse.

Denyse had been the great passion of Simenon’s life, but she was complex and exhausting. After they separated Simenon managed to get her admitted to a mental hospital, but he never divorced her. Instead he just replaced her with Teresa, his wife’s housemaid. Teresa was an unpretentious person who in some ways rather resembled the fictional Madame Maigret, the loyal woman who is always waiting up for her husband with something delicious in the oven. And Teresa also resembled Simenon’s mother. Both saw themselves as members of les petits gens, the ordinary people whose values the novelist admired. Simenon and Teresa lived together in a modest villa on the shores of Lake Geneva, and she looked after him attentively until his death in 1989.

Much as I enjoyed the Maigrets, my preference was eventually for the darker novels; and perhaps that was one reason why I called my life of Simenon The Man Who Wasn’t Maigret. He wasn’t Maigret, but he sometimes probably wished he had been. It was when the German occupation of Liège ended in November 1918 that the trouble really started. There was a bloodthirsty settling of accounts. Law and order broke down, looters and vengeful mobs ran through the city, and one man mistakenly suspected of collaboration who had sought refuge on the roof of his house was surrounded by the crowd and urged to jump. This incident, witnessed by Simenon, eventually inspired the climax of the plot in one of the earliest romans durs,Mr Hire’s Engagement (which will be republished by Penguin in November).

To be commissioned, as I was, to write a life of Simenon while living in Paris is probably some people’s idea of heaven. It was certainly an interesting way of exploring Paris. Sometimes a Simenon character would unexpectedly spring to life before my eyes. I used to work through the lunch hour in a succession of favourite cafés. The waiters would succeed each other during the course of the working week, depending on whether I felt like an onglet au poivre or perhaps preferred uneassiette ‘croix-rousse’. On one occasion one of these waiters, an impatient and bad-tempered little man who Maigret would have savoured and who usually told me what to eat, seized my research material, glanced at the cover and tossed it back. ‘Ah oui’, he said, ‘c’était le médecin.’ And it was indeed the doctor who had done it.

Patrick Marnham was literary editor twice in the 1980s.

Comments