The link between a healthy mind and a healthy body was understood by Juvenal — but he didn’t have to raise two kids in our brave new world of social media and fast food. We’ve all seen the stats, so there’s no need to repeat them. But as snacks replace square meals and the virtual world replaces the real one, our children are becoming increasingly sedentary and unhealthy.

For parents of school-age children, sport has never been more important. But making sure kids get a good sporting education is no easy matter — and I should know. In my experience as a parent (and briefly as a teacher), sport in the state sector is usually pretty patchy. Teachers do their best, but they’re beset by all the usual problems: big class sizes, inadequate facilities… you’ve heard it all before.

What’s so tricky about teaching sport is that teachers need to cater for two sets of pupils: the handful of youngsters who might play at the top level one day if they’re given the right start, and the rest of us, who simply need to cultivate an active lifestyle.

When I was a spotty schoolboy, at an old-fashioned grammar school, there was no doubt which of these objectives took priority. Our PE teachers were on the lookout for the next superstar; the rest of us were more or less forgotten. Hence, most of us hated PE and bunked off whenever possible. Luckily, we spent our free time playing football, so we stayed fairly fit. Unfortunately, today’s youngsters aren’t so lucky.

When my son was small I took him to the park to kick a ball around and, much to my surprise, it turned out he was pretty good. Now I had the opposite problem to the one that plagued my schooldays — how could I give him the sort of start which would make the most of his sporting talent? Unlike my old school, his primary school wasn’t at all competitive. Rather, it had adopted the Alice in Wonderland approach that’s so prevalent in state schools (‘Everybody has won, and so all must have prizes,’ as the Dodo says).

The only solution my wife and I could find was to outsource our son’s sporting education. He joined a local football club, got scouted by Watford FC, and played for them for the next eight years. When he was 11 he got a ‘Gifted & Talented’ place at the Harefield Academy, a comprehensive in north-west London where the Watford schoolboys train. Harefield gives Gifted & Talented places to all sorts of sporty kids, not just footballers, and the presence of these committed youngsters, from a range of backgrounds, benefits the whole school. Sure, it has a mixed intake, but his teachers were brilliant and the sport superb.

Sadly, my son was let go by Watford when he was 16 (many are called but few are chosen) but the club put him in touch with Bradfield College, a leading independent school with a great reputation for football, which gave him a football scholarship. He’s there now, doing four A-levels and playing for the Independent Schools national team. However, it was his teachers at Harefield who got him there, guiding him to five A*s and five As at GCSE.

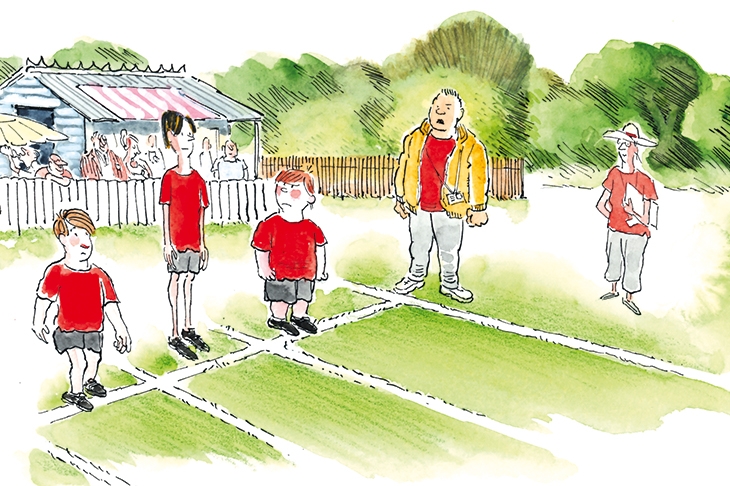

For my son, this is a story with a happy ending but in fact his experience isn’t such a great advert for elite sport in state schools: Watford didn’t spot him while playing for his school team, and he couldn’t have got into Harefield without playing for Watford, as we lived outside the catchment area. If we’d left it to his primary school he might never have got started, playing 15-a-side on an asphalt playground barely bigger than a tennis court. And anyway, what about the rest of us? Most of us aren’t elite athletes. ‘Without the willingness to accept one’s imperfections, we too easily fall into the vulnerability trap of developing ourselves as far as we feel safe for that fear of failure or being found out,’ observes Samantha Price, headmistress at leading girls’ boarding school Benenden. ‘Do not worry about being perfect.’ We need PE teachers who’ll inspire us to muck in and get our knees dirty, and keep on doing that throughout our lives, even if — especially if — we’re not that sporty.

Seeing my son play for Bradfield against other independent schools has been a revelation. The standard of first-team football is high (quite a few of the coaches are ex-professionals) but what has really impressed me is how many teams these schools put out. On this circuit, competitive sport isn’t just for sporty kids — everyone gets a game. Clearly, the benefits are huge, particularly for the least sporty pupils. They learn the value of taking part and getting better at something they’re not particularly good at, and they acquire a habit that lasts a lifetime. Meanwhile, pupils at state schools need to excel at sport to get any of the same benefits — and even then the opportunities aren’t that good.

So how can state schools match the sporting prowess of the private sector — not only for elite athletes like my son, but for children like my daughter, who wants to stay in shape but finds PE lessons at her local comp uninspiring? Comprehensives need to emulate schools like Bradfield and field loads of teams. Bradfield has 23 football teams, including a Seventh XI. Imagine the difference it would make if state schools did the same. Competitive sport at my grammar school was demoralising because most of us weren’t included, but avoiding competition isn’t the answer. If every pupil is involved, competitive sport can be liberating. As Alice understood, games are meaningless if all must have prizes. And as schools like Bradfield understand, the biggest prize in any sport is the pride of playing for a team.

Comments