In this compelling book, Matthew Hollis analyses how Edward Thomas, for years a frustrated literary critic and prose writer on rural themes, became all at once, at the age of 36, a poet of genius. It was his close friendship with the American poet Robert Frost which, in 1914, precipitated this long-delayed fulfilment.

Married while at Oxford University, Thomas, to support his wife Helen and the three children whom they rapidly produced, burdened himself with writing ill-paid book reviews — sometimes as many as 15 a week. Of his own numerous books some were potboilers, others more distinguished, and all rather heavy in the hand, including the life of his hero, Richard Jefferies, the great 19th-century nature and country writer.

Thomas’s acute judgment, especially over new poetry, was soon recognised, but this did not make him rich. As their resources fluctuated, the Thomas family moved from one picturesque rented rural slum to another, at one time inhabiting a freezing Arts & Crafts house built by a friend. Helen, whom he often blamed for trapping him in this existence, would have benefited from a hairdresser, but had, according to her own account, a beautiful strong body.

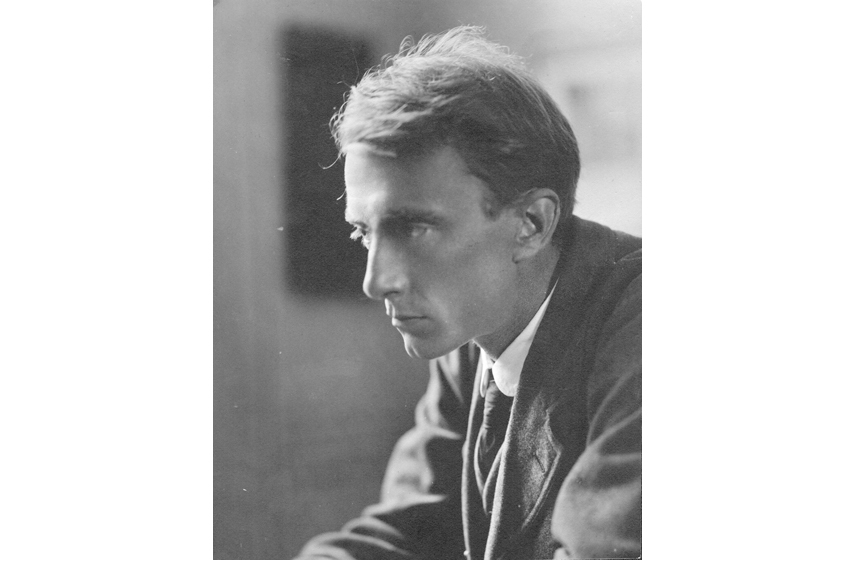

On his periodic visits to Fleet Street, Thomas made a memorable impression. According to a contemporary journalist:

He walked with a sort of lope, half springy and half lackadaisical … from youth to prime a face austerely beautiful, vivid in the intensity of its tan, candour of its blue eyes, and bleach of Saxon hair…an introspective Pan whose arm pressed to its side not the syrinx but, odd anomaly, a couple of review books,

Poverty and frustration played havoc with Thomas’s nerves. Consumed with self-hatred, he brooded on death and the tragedy of life, once even contemplating suicide with a rusty firearm; and though he loved her, he lacerated Helen with his eloquent tongue, frequently storming out of the house, regardless of the weather, on one of his gigantic rambles, through which he hoped to achieve calm, but often returning home as tormented as before.

His incessant walking gave him the intimate knowledge of the byroads and field paths of the southern counties that he was ultimately to turn into poetry. Years later, Helen, ever-forgiving, wrote an account of their marriage, sexually frank for its day, not leaving out the quarrels, but presenting a rural idyll. It is, apart from his poems, his most moving monument.

Edward Thomas’s friendship with Robert Frost flowered during 1914 in Herefordshire and later Ledington, near Dymock, in Gloucestershire. Frost, also a countryman, had gravitated to England, where, disappointed by his poetry’s reception in the USA, he hoped to achieve recognition — as he did from Thomas. Together they went on long walks. Frost’s conviction was that poetry must communicate by intonation and rhythm as well as through the literal definition of words, cadence being fundamental to human speech. These views were close to those Thomas had already struggled to express in his own criticism.

Frost gave Thomas the courage to start writing poems. Among the most fascinating aspects of Hollis’s book is showing how Thomas transformed the contents of his past notebooks into powerful and haunting verse. He admired Frost, both for his passionate convictions and for his physical bravery. Not that Thomas himself lacked courage. He volunteered for the army in 1915 when, as a married man, he could honourably have remained a civilian. He proved an efficient soldier in the heavy artillery, intensely disliking the discipline but working hard at map-reading and gunnery. A Welshman, he was not driven by conventional English patriotism, hatred of Germany or love of British institutions, but by the feeling that he could not stay at home while others suffered in the trenches, by a desire to show manliness, and by that side of him that welcomed death; and above all, by his deep feeling for the English countryside.

For despite its repeated theme of the dark mystery of extinction awaiting everyone, the verse of this complex man celebrates as well as broods. As with Frost, fear, struggle and the sinister play their part — the wild cry of ‘The Owl’, the gamekeeper’s ‘Gallows’ — but for Thomas the natural world was above all a source of joy and love: ‘The great diamonds of rain on the grass blades’ (‘It Rains’); the bitter scent of ‘Old Man’ with its tantalising message; and the birds in his most famous poem, ‘Adlestrop’: ‘For at that minute a blackbird sang/ Close by, and round him, mistier,/Farther and farther, all the birds/ Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.’

Although he is often labelled a war poet, little of Thomas’s poetry was directly focused on his army life, and none was written on active service. He had only been three months at the Front when he was killed on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917, on the bitterly cold first day of the battle of Arras, one of the largest of the war. He would have been drily amused at the choice of his later burial place, the cemetery at Agny. That village, once resounding with the clang of shell fragments on the paved squares of nearby Arras, was known to the soldiers in that sector of the line as ‘Agony’.

Comments