Matthew Parris has narrated this article for you to listen to.

On Thursday 16 August 1739, the young John Wesley met and for an hour argued with the middle-aged Bishop of Bristol, Joseph Butler. It was an ill-tempered encounter. Wesley believed that God communicated directly with individuals, invested his promises and purposes in them personally, and charged them with missions to reveal and explain the divine will. Butler, famous for his rationalism, reacted with cold indignation. ‘Sir,’ he told Wesley, ‘the pretending to extraordinary revelations and gifts of the Holy Ghost is a horrid thing, a very horrid thing.’

The Bishop spoke for England. We do not ‘do’ God – not even the 49 per cent of us who actually believe in God. We are of course hardly immune to evangelical enthusiasms: they often flare up among us and the Wesley brothers caused a conflagration. But they trigger a strong rejection. Nor do we greatly like, or like for long, moral crusades. The result of this innate national scepticism is that the proclaiming of moral zeal, or calls for a moral revival, induce in millions an unmistakable queasiness.

I feel the same queasiness about last week’s Alliance for Responsible Citizenship (ARC) conference, whose organisers insist that faith and politics do not mix, yet whose language was steeped in moral fundamentalism and peppered with references to ‘Judaeo-Christian’ values. To this in a moment.

The alloy of scepticism and suspicion towards spiritual and moral certainty runs very, very deep among us. ‘Things have come to a pretty pass,’ remarked Queen Victoria’s first prime minister, Lord Melbourne, ‘when religion is allowed to invade the sphere of private life.’ He was only partly joking. His indignation was not so much theological as drawn from an Englishman’s sense of moral privacy and inclination towards ‘live and let live’.

And so it was with Butler’s, Melbourne’s and my own misgivings that I’ve been watching YouTube extracts from last week’s ARC conference. It was convened by the Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson, a moral, cultural and political internet prophet with a huge international following among youthful (and overwhelmingly male) conservatives. Before a sellout 4,000-strong audience, this massive three-day event at London’s ExCel Centre saw interviews with prominent conservative thinkers and political leaders around the world, from Australia’s religious Tony Abbott to Britain’s more circumspect Kemi Badenoch.

Now, you can address an organisation without subscribing to all its aims, and these luminaries’ appearance did not imply membership of ARC. But this was as much a rally as a conference, and appearances on the podium looked and sounded like an attempt by each speaker to associate themselves with the movement. I’m told by friends who were there that there was a palpable sense of excitement – and the after-party in Soho, D’ARC, felt (according to the Londoner newspaper) positively electric.

To me this all had a curiously familiar ring. Readers of a certain age may remember from the 1950s and 1960s an American-inspired movement called Moral Re-armament (MRA). It was big for a while, and gathered an enthusiastic global following, including here. Its founder and leader was a right-wing Evangelical churchman called Frank Buchman, an advocate of sexual probity and family life. Pre-war at Princeton, students of his putative movement were encouraged to make public confessions of their sexual indiscretions. Buchman believed that moral degeneration rendered us vulnerable to communism. US presidents approved. Rumours of CIA backing were never substantiated but Buchman (I think shrewdly) began downplaying the Christian element, holding enormous rallies across the world and constructing a lavish permanent base on an island in Michigan.

Calls for a moral revival induce in millions of British people an unmistakable queasiness

Yet somehow a shadowy aura always clung to MRA. I recall that people didn’t always tell you at first that they were linked to the movement. Rather as with C.S. Lewis’s covertly religious tales for children, there could be a sense of something fishy going on, of moral ambush.

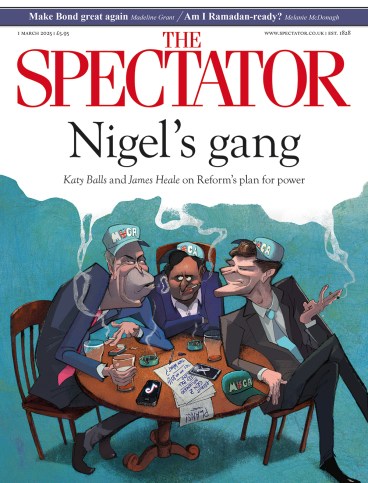

At that ARC event, I noticed even Nigel Farage – who has sensitive antennae about where his support comes from – slightly squirm in his interview with Jordan Peterson. Peterson was dog-whistling to a whole kennel of pooches. Artfully, he steered just clear of overt queer-bashing, abortion-denying, divorce-disapproving or single-mum-blaming. After ‘tolerance’, he told Farage, ‘the core of civilisation… that we’re attempting to reinvigorate is a commitment to long-term, stable, married, monogamous, heterosexual, child-centred marriages’.

Interrupted by prolonged applause, he was encouraged to continue. ‘That’s a fairly restrictive ideal, and, you know, ideals are restrictive.’ ‘There’s going to be deviations from the norm,’ he acknowledged, but ‘stable, long-term, married, monogamous [etc]… is the kind of commitment to community, to sacrifice, to future, that’s the fundamental unit of civilised society.’

Event

Spectator Writers’ Dinner with Matthew Parris

I watched Farage. One sensed him going a bit green about the gills. Finally he observed mildly that after two divorces he was not the best advocate of heterosexual monogamy but he did believe in family. He looked wary.

I think British conservatives should be wary too. This column’s aim is not to dispute the idea of a moral and political revival. Nor is it to deconstruct the buzz-term of the conference, ‘Judaeo-Christian’. My aim is to warn conservatives that whether or not ARC’s purposes are laudable, for the British right the movement is a trap. Note Donald Trump’s proclamation that it was for God’s purposes that he was saved from assassination. Imagine British voters’ response to such a claim. We are not the same as America.

When considering the support you’ll gain by embracing a movement, you should consider too the support you risk losing. My own instinctive recoil from something that, though I struggle to define it, I find creepy, would be mirrored by millions of Britons.

And guess who they’d predominantly be? Fundamentalist Muslims would, of course, applaud every word Peterson spoke. No, the shudder would come from the very people – overwhelmingly white, often conservative voters who’d say their values were Judaeo-Christian – but who don’t like their politicians to preach. They find this stuff – how shall I say? – weird. So do I.

Comments