When the revolting news broke that Keir Starmer – whingeing lovechild of Oliver Cromwell and Captain Mainwaring – could be about to ban smoking in parks, public restaurants and beer gardens, I couldn’t help but think elegiacally of my own lifelong love/hate-affair with the pernicious weed, and to nicotine glories past.

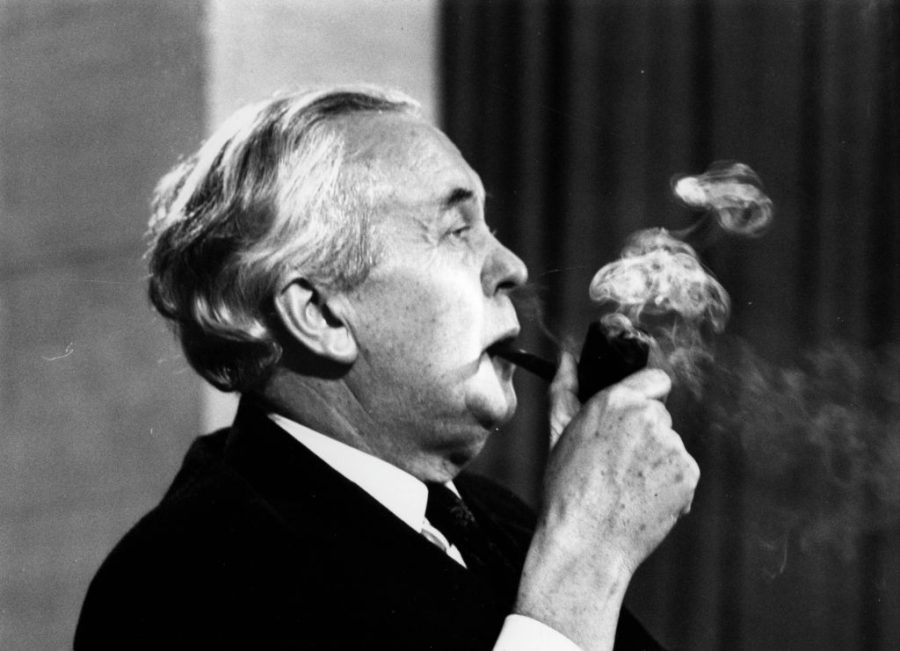

I was 13 when I started smoking in earnest and had been impatient to develop the habit long before that. Back then everyone smoked, and they did it everywhere too – on buses, in trains, on the underground and at the cinema. We were a tobacco culture: chat show guests would puff away languidly, the former prime minister Harold Wilson had just stopped rebuffing Robin Day’s questions by firing up his pipe and some houses had tabletop lighters and cut-glass ashtrays to sanctify the habit for their guests.

Back then, society was neatly divided into smokers and non-smokers

Children would be sold candy-cigarettes in facsimiles of the adult packet – ‘Just like Dad’ said one advert – and most of us couldn’t wait to convert those sugary sticks into the real thing. Smoking was a rite of passage, a marker of maturity, with different cigarette-brands and their packet designs taking the place, as you hit your teen years, of childhood gobstoppers and Aero bars.

The summer I started smoking I’d just left prep school, and the heady sense of freedom (we’d just bought our first video player too) was maximised by this new, joyful habit. We had a lodger at the time who worked on an American airbase and could get a carton of 200 Marlboro for exactly £3, the kind of sum you could (mea culpa) secretly ‘borrow’ from your parents without dropping yourself in it. I taught myself doggedly to enjoy tobacco and, by the time I did, it was too late to stop.

Not that I much wanted to. I loved everything about smoking and felt as though I’d discovered a vocation. There were the cigarette packets, all of them faintly iconic: the deep purple of the Silk Cut square (what a smoke for all seasons Silk Cut was!), the lavish gold (just the right side of vulgar) of Benson and Hedges, the baronial flat packet of Dunhill (favoured by gangsters, apparently, as it didn’t ruin the line of their suit). There were the three red K-shapes of the Marlboro packet, with the urban myth that they referenced the Ku Klux Klan.

All the smoking paraphernalia was part of the fun too. Those spinning ashtrays that centrifugally flung the cigarette butt into an odorous hell beneath, or special cigarette dispensers (I remember a wooden donkey, bought from an Ipswich junk shop, which, at a lift of its tail, casually shat a Gauloise for you). Hotels and bars had matchbooks to filch, or – if you were flash – nestling in your pocket was a Zippo Lighter (edgy and American) or an effortlessly elegant Dunhill Rollagas, purchased in St. James’s with your Christmas money.

Back then, society was neatly divided into smokers and non-smokers, and it appeared (in adolescence and beyond) to be a way of classifying people and quickly knowing something about them (I suppose, in these post-tobacco days, woke and non-woke has replaced it).

To be a young person and not to smoke seemed to be missing out. All the idols you’d inherited – Lou Reed, Bob Dylan, even Jean Paul Belmondo – would have been diminished without a cigarette in their hands or gob, and you wanted to emulate them. There was the flirtatious move of lighting a cigarette for someone, of sparking up one cigarette from another, of learning to blow smoke-rings.

Our breath, our clothes, our hair smelt, but we were tolerant enough with each other not to care. People who wouldn’t let you smoke in their houses seemed odd and finicky, and those who came out with things such as ‘Kissing a smoker is like licking an ashtray’ seemed sa-a-ad. Richard Burton spoke of ‘that killing cigarette between my lips, how I love its round cool comfort’. Dennis Potter, who smoked till the day of his death, called it ‘this lovely tube of delight’.

Of course, all this had a hangover. In many ways, anyone born after 1970 was lucky – their habit has waned and grown threatening at the exact moment those exquisite packets have vanished to be replaced by dull cardboard and a picture of rotting lungs. This of course hasn’t put many off but has at least taken the Mayfair sheen off the practice. Reports in these pages that anyone who smokes past the age of 35 is doing serious damage to themselves ring horribly true (I myself had to give up tobacco completely this year following complications, putting the kibosh on my beloved new pipesmoking habit, and should surely have done it earlier).

I’ve often questioned my smoking over the years – why was the one cigarette or pipe out of twenty that actually hit the spot enough to keep me hooked? Was smoking simply the softest possible way of beating myself up for imagined misdemeanours and subtly contributing to my own non-survival? Did I just enjoy addiction, that sense, 20 or 30 times a day, of coming home? Not even copious tobacco has helped me arrive at answers to these questions. The fact remains though that it’s almost impossible to imagine my teens without a fag in my hand and the pleasant feeling I was doing something naughty that had to be kept from the grown-ups.

This feeling, of course, has made a comeback. That the 2007 smoking ban was grudgingly accepted is perhaps because we smokers, in our teen years, had been schooled in what it meant from the start. We were all now, once again, puffing away behind the bike sheds, forced into the open air to congregate with our own kind, away from the walls which had ears.

Though smoking – in TV series and movies at least – had moved away from the realms of cool to become a signifier of human vulnerability, there was still a sense, in those huddles outside pubs or workplaces, of belonging. Portmanteau words like ‘smirting’ (smoking + flirting) sprang up, to describe what often went on outside a pub. Addicts, as they always do, found that no obstacle was enough to put them off.

Starmer – who has the permanently hurt look of a schoolmaster after the choir have misbehaved on an outing – and his band of gurning non-smokers have declared war on the very remnants of this habit. This hints at something obsessive and vindictive in their nature and is a lousy augury for the next five years.

The wide unpopularity our new PM has managed to secure himself in a matter of weeks (with his personal rating dropping 16 points) suggests that the British people, having wearied in the past few years of a government they despised, have instead opted for one they can actively hate. ‘Giving up smoking doesn’t make you live longer,’ went the old joke, ‘It just feels like it,’ and the same could surely be said of our new ‘changed Labour’ government.

Chewing tobacco, anyone? Pinch of snuff? Nicorette throat spray? I fear we shall need all the stimulants we can legally lay our hands on, to make it through the fallout clouds to 2029.

Comments