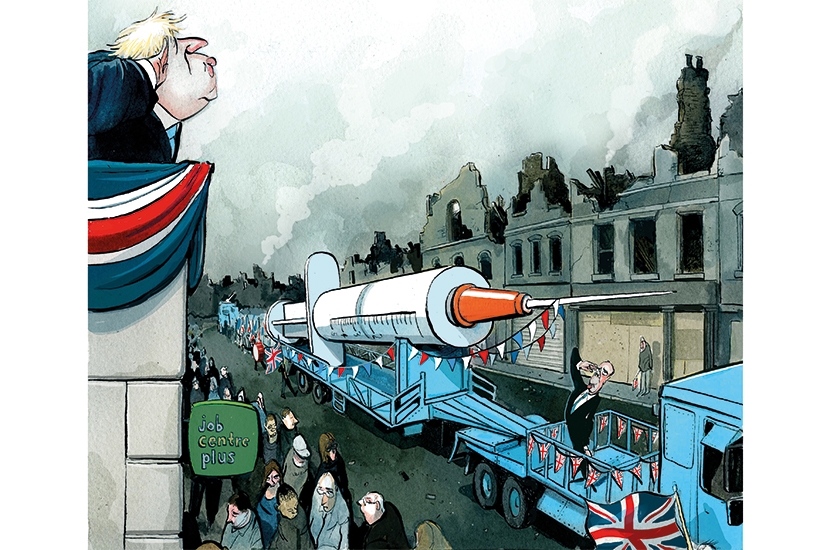

Ever since the pandemic struck, a spectre has haunted Boris Johnson: would Britain ever escape from this? His scientific advisers had given him a terrifying vision. Only 7 per cent of the public had caught Covid in the first wave, they said, meaning 93 per cent were still susceptible. So what was to stop his premiership being a never-ending cycle of lockdowns? Now, he has his answer: not one but three vaccines, two with efficacy rates of 95 per cent. This has transformed his outlook. The war against Covid is not over, but victory looks imminent.

The Prime Minister has a weakness for wartime metaphors, but this time they are more appropriate than he might find comfortable. For months, his government has had one overriding priority: defeating the viral enemy, no cost spared. But decisions made in the heat of battle will go on to define the rest of the decade. Victory comes at a huge cost. We can calculate the damage to the national finances, but the effect on education, mental health, employment and society remains devastating.

This, now, is the mission facing the government. ‘Everything will depend on what we do next,’ Johnson told allies a few weeks ago. Labour, he said, will come up with its solutions: big government, huge taxes, minimal personal freedom. And what the Tories propose could define politics for the next decade. He describes it as ‘the biggest political argument of my lifetime’ — and one, he says, that the Conservatives need to win.

Before the big argument, there are many smaller ones. Tory MPs are already grumpy about the fact that restrictions will continue until spring. They are determined to ensure that there is a day when all the Covid-related rules go. One senior backbencher tells me: ‘There has to be a campaign to make sure this happens.’ He warns: ‘If there isn’t the determination to sweep this away, it’ll linger for years. It’ll be like rationing after the war.’ Given Johnson’s own instincts and the necessity of him improving relations with his parliamentary party, we can expect there to be a day — probably sometime in early April — on which all such regulations end.

Many Tory MPs worry about a political form of ‘long Covid’, of heavy-handed government restrictions lasting for months or even years. The state has just intervened in the economy in unprecedented ways; civil liberties have been suspended. After both world wars the country moved to the left, with the role of the state expanding. The test for Johnson is to prevent this from happening again. A further, permanent expansion of government would turn Britain into a social democratic state with a permanently low growth rate.

Decisions made in the heat of the battle will go on to define the rest of the decade

With the vaccine, it’s possible that we will see a snap back to normality more quickly than many had expected. Restaurants will be able to fill every table, offices operate at full capacity and (perhaps less enticingly) commuter trains will be crowded again. In these circumstances, ministers expect an economic rebound stronger than predicted. This is not the result of naive optimism, but the experience of the first wave.

After the first lockdown, the economy grew 16 per cent — and that was despite firms being acutely aware that restrictions were still in place and were bound to tighten if infection rates rose. Andy Haldane, chief economist of the Bank of England, pointed out that the recovery had been better than anyone expected — perhaps because companies were more resourceful in adjusting to new rules. They still had a massive handicap, but with the Covid drag-anchor removed, the economy should come back strongly.

A financial recovery may cut the deficit, a vaccine may be able to ward off infection — but neither will remedy the scarring that lockdown will leave behind. The year of Covid restrictions will have widened the already existing inequalities on a scale that is literally unquantifiable. That exams were replaced by teacher predicted grades this summer means there can be no true assessment of who has fallen behind — in a knowledge-based economy this threatens to stymie life chances. But the coming exams in England will reveal the extent of the damage. I understand that these exams will be accompanied by a series of ‘fairness measures’ to try to ensure that those who suffered most under lockdown are given some leniency. Pupils will likely be given some notice of what will be in the tests, with further education institutes and universities pushed to be ‘generous’ in their admissions.

The view in Whitehall is that it will take two to three years for the effect of lockdown to ‘wash through’ the education system. And that will be true on a broader scale: the 2019 mission of ‘levelling up’ will now be a mission to repair the damage inflicted in 2020.

The past decade was defined by the British ‘jobs miracle’, with the number of new jobs created repeatedly beating the forecast. It will be very different this time. George Osborne dealt with a recovery that was weak on productivity but strong on employment numbers. This one will be the opposite way round. Lockdown and social distancing means businesses have discovered ways to operate with a smaller number of people, and that will have a lasting effect long after the restrictions are gone. For example, the shift to online retail will not be reversed — and online retail simply requires fewer staff than the high-street version.

Inside government, job creation is regarded as the biggest economic and political problem of next year. The unemployment rate may now be low — at 4.8 per cent — but almost 2.5 million workers are on furlough, with no telling how many of their jobs will be around when the scheme ends. We can add to this the obvious threats of the new remote-working template: if you can do your job from home in Britain, can someone else do it from abroad for a fraction of the cost? There’s scope for ministers to act now, before irreversible decisions are made.

The normal tool — a tax cut, perhaps lowering employers’ National Insurance — would be a blunt instrument. Far better to return to a version of the ‘job support scheme’ that was launched in September before being replaced by the return of furlough. This would pay employees for hours not worked, so companies can reduce costs without losing staff entirely. This would also have the effect of supporting small shops and hospitality which will be in particular need of help after the pounding they have taken during the pandemic.

This will cost — and, sooner or later, the Tories will have to balance the budget. This will mean tough choices. The 2017 campaign showed what happens to the Tories when they don’t create a firm fiscal dividing line: then they struggled to land a blow even on Jeremy Corbyn’s madcap spending plans. As one Tory who is especially exercised about the Scottish Nationalist threat warns: ‘If you can borrow unlimited amounts of money, then what’s the case against Scottish independence?’ (Of course, an independent Scotland would not be able to replicate the UK government’s actions as it would not have its own currency, and thus its borrowing power would be severely constrained.)

The smaller the economy, the tougher those choices will be — so the Prime Minister’s plan is to go for growth. When not talking about Covid, he enthuses about ‘an indecent amount of brilliant ideas’ waiting in the wings to speed up the recovery. But so far, there’s only one radical supply-side reform: overhaul of planning, and even with this large numbers of Tories are mobilising against the proposed reforms. There may well be a case for tweaking the precise algorithm used to determine what the housing target for each local authority should be. But for ministers to cave in now would be to abandon the growth agenda before it has properly begun. A failure on housebuilding would be particularly costly, because if the under-forties feel excluded from the property-owning democracy they will veer even more sharply to the left, reinforcing the Tories’ demographic problems.

By some estimates, the damage of lockdown has wiped out ten years of progress in closing the school attainment gap between rich and poor. So how to repair this gap in short order? One tool that will be used more is one-to-one tuition. It’s expensive, so its effectiveness is being closely monitored. A rule of thumb is being assumed: that two hours of personal tuition a week for 12 weeks will be the equivalent of three to five months in the classroom. If this turns out to be the case, tutoring could be transformative in terms of reducing the attainment gap in future.

The legacy of this year on the nation’s health will be dire too: the collapse in use of GPs could well translate into more cases of avoidable diseases. Already the number of people waiting over a year for an operation is the highest it has been since 2008. At the last count, some 1.7 million had been waiting more than 18 weeks to start treatment. But these figures, bad as they are, don’t tell the full story. People have been avoiding seeing their doctor throughout the pandemic; the number of GP referrals is down by a third this year. The worry is that as life returns to normal, more people will come forward and their delay in seeking treatment will mean they will need more urgent intervention.

The Health Foundation estimates that restoring waiting-time standards by the next election will cost £1.9 billion a year — and this is only the cost of addressing the physical health legacy of this crisis. The main rationale of lockdown was the belief that the Tories could not afford to see the NHS overwhelmed by Covid cases. But there is a danger for the Tories that the waiting lists left behind by Covid could enable Labour to once again deploy its favourite line: you can’t trust the Tories with the NHS.

Up till now, this country has not handled Covid well. The UK has one of the highest death tolls in Europe and its economy has taken one of the biggest hits. But the £3 Oxford vaccine — which only needs to be kept at fridge temperature, making it simpler to roll out than some — offers an escape route. It is also a reminder of the world-class research base there is in this country.

The scientific breakthrough nods to what Britain, as a country, is capable of. The capacity for discovery and renewal: this is a theme that suits Boris Johnson much better than the grimness of pandemic management. But the forecasts produced on Wednesday — which show borrowing at £394 billion this year and over £100 billion for every year in this parliament, and predict that the UK won’t return to pre-Covid levels of GDP until the final quarter of 2022 — are a reminder of just how bad a dent Covid has put in this country’s finances. The Tories need to repair this damage and renew the social fabric. If they fail, this country will turn to the left again.

Comments