Most cultural tourists, apart from the Japanese, skirt the six towns of Stoke-on-Trent. They are wrong. The bottle kilns have tumbled and the smoke-ridden skylines are no more. Yet museums teem with quality. And remaining pottery firms disclose glimpses of the design and craftsmanship admired throughout the city’s history.

The founding father of Stoke’s global pre-eminence was Josiah Wedgwood, perhaps the most talented all-rounder among British industrial revolutionaries. His achievements are the subject of A.N. Wilson’s latest novel, The Potter’s Hand. It closes with Wedgwood’s death.

Nearly 30 years ago Wilson completed a biography of Hilaire Belloc, an even more prolific writer than he himself. He explained that towards the end of the bellyacher’s life a friend enquired whether his best books were written for love or money? ‘Always money,’ rasped Belloc. This novel of Wilson’s was conceived through love, even passion. His father was managing director of Josiah Wedgwood and Sons when Wilson was a child. He began the book on hearing about the threatened demise of the Wedgwood Museum.

Perhaps it might have been easier for Wilson to place history before art by writing another biography of Wedgwood on the heels of Brian Dolan’s Entrepreneur to the Enlightenment, published eight years ago? Wisely, he avoided the temptation, as well as curbing several colossi of the age from overshadowing the narrative of his novel. They are mostly given cameo roles.

Thomas Paine, corset-maker and half-cocked revolutionary, huffs in Philadelphia. George Stubbs, the brilliant sporting artist, botches a portrait of humans. John Wesley is dismissed by the Unitarian Wedgwood as a windbag and inciter of collective hysteria. And even the Lunar and Royal Societies, where the master potter beguiled a galaxy of fellow members, receive just passing salutes.

Instead, the novel spotlights the everyday tales and relationships of a close-knit group of pottery folk performing extraordinary deeds. Though chiefly founded on fact, the subtleties of the links between Wedgwood’s coterie enable Wilson to enjoy liberties afforded by historical fiction. As a biographer of Sir Walter Scott, he knows as much as any romantic about the advantages of this writing style. The author has described Scott as ‘the greatest single imaginative genius of the 19th century’.

This book will thwart those who like to criticise Wilson for his opinions on religious doctrines and wider creeds. They barely surface here. The author has reached an age — and of course it comes to many writers — when he needs to return to his roots. Yet rather than engage in nostalgia for greengage Staffordshire summers full of illusions of hope, or anger about the abominations of parents, Wilson accentuates Wedgwood’s humanity. Josiah is the genius, whose 200-year legacy gave work to Wilson’s father and tens of thousands of others, as well as equipping the author himself with a 1950s Potteries upbringing.

Wilson faced a hazard. In view of family sympathies, his pen could have been dipped in syrup. But the risk is dodged at every stage. The Potter’s Hand combines striking passages of prose with credible dialogue stripped of comfort and sentimentality. It is a fluent tale, and gritty at times about the boldness, foibles and magnificence of those major 18th-century figures, the first industrial revolutionaries.

Wilson’s imagination, recalling Scott, creates an important fictional character. She is a Cherokee Indian damsel named Blue Squirrel, the object of the attentions of Wedgwood’s nephew Tom Byerley, the young man having been despatched to America (as he was in reality) to buy clay from the Cherokees for his uncle’s pottery.

Blue Squirrel emerges with formidable talents at intervals throughout the book. This is not far-fetched. The Cherokees were as civilised, if not more so, as Scott’s romanticised Scottish Highlanders of the same era; and traders, such as Byerley, often married their women. Some offspring of these unions rose to positions of tribal leadership, and one became the last Confederate General to surrender during the American Civil War.

Byerley, a failed actor, struggles for independence from his all-controlling uncle, whose competitiveness and hyperactivity make him the toughest of patriarchs, inventive enough through experiments to revolutionise the European ceramics industry.As a self-educated polymath, Josiah mixes entrepreneurial ingenuity and scientific curiosity with Enlightenment values, and becomes a model employer, caring more for forthright, radical beliefs than popularity and social acceptance. He is an admirer of Charles James Fox, and a friend of Thomas Clarkson: no political convictions matter more to him than support for colonists in the War of American Independence and hostility to slavery. Medallions, called cameos, are produced to underpin these principles, depicting a kneeling slave bearing the inscription: ‘Am I not a man and a brother.’ The recipients include another friend, Benjamin Franklin, a polymath of even grander proportions.

The worth and choice of Wedgwood’s two principal friendships further enhance his eminence, and spark a leading British intellectual dynasty that flourishes to this day.

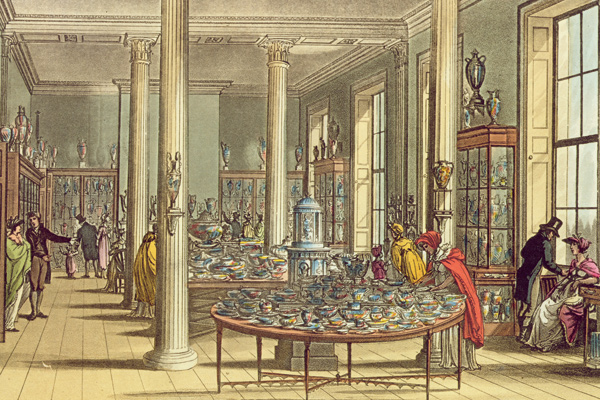

Thomas Bentley, a Liverpool merchant intrigued by science, possesses marketing skills. His partnership with Wedgwood becomes one of the most significant of the early Industrial Revolution, urbanity complementing bluntness. Bentley makes his friend’s ceramics fashionable by opening showrooms in London. Patrons include Queen Charlotte and Catherine the Great. The devious yet enlightened Empress commissions a dinner service of more than 950 pieces. (This is on show in Edinburgh until October.) Of course, the new bourgeoisie charge into the showrooms to mimic royalty.

Wedgwood’s other close friend is a physician and philosopher, Erasmus Darwin. A Fellow of the Royal Society, the scientific networker and opium-pusher is the Wedgwood family’s counsellor and champion. He arranges the marriage of his son to Wedgwood’s daughter.

In reality, this couple became the parents of the naturalist Charles Darwin and a great clan took shape. So far, eight generations on, it can claim at least ten Fellows of the Royal Society, notable artists, writers and musicians, including Ralph Vaughan Williams as well as members of the Keynes family. It is a cousinhood of genetic brilliance.

Simultaneously, the Wedgwoods also remained an unusual family. Instead of forsaking their roots for lives of rural romance and social escalation like other heirs of tycoons, they remained loyal to their firm, the Potteries and political radicalism. So much so that the first Lord Wedgwood, offered a peerage in 1942 by Winston Churchill, had been a Labour MP and former member of the ILP. When he joined the Home Guard, a colleague requested an autograph.Wedgwood scrawled his signature before adding ‘to a fire worker from a firebrand,’ showing that 200 years later he was a chip off Josiah’s Jasperware.

Perhaps one or both of these remarkable families could furnish Wilson with ideas for a sequel?

Comments