The overturning of Roe v. Wade is an American story, and a global one. What the hell – it’s asked with some justice – does it have to do with the rest of us? In part because, as is sometimes said, when America sneezes the UK catches a cold. But also because the intoxicated global reaction to what, looked at from one angle, is a narrow point of US constitutional law, shows us something about where we’re at.

As someone generally of the liberal tribe I find myself slightly out of kilter with my natural allies on this subject. I’m as horrified as the next bloke in a ‘this is what a feminist looks like’ T-shirt at the ‘trigger laws’ which at a stroke will curtail women’s bodily autonomy across huge swathes of a supposedly civilised country. That said, it doesn’t seem to me to be so obvious as needs no argument that abortion is an unqualified human right.

To define the debate as pro-choice versus pro-life and to ask us to pick a side makes a matter of deep moral importance into a culture-war ding-dong. The polarising focus on edge-cases makes it worse. Conservatives like to talk of ‘abortion on demand’ as if the liberal position is a frivolous form of consumerism. Progressives zero in on how abortion laws could cause children conceived in incestuous rape to be carried to term – as if pro-lifers are all Gileadean sadists for whom this is the basic idea.

Very few people in the pro-choice position think that aborting a foetus two or three days before it comes to term would be anything other than monstrous. At the other end of the process, there’s an attractive clarity in the position that the instant a sperm breaches the cell wall of an egg the resultant object is a human being owning sacred rights of personhood – but that’s a theological assertion rather than a moral argument. Where it’s coupled, as in the laziest version of it, with an uncompromising disregard for the existing personhood of a pregnant woman, it abdicates the claim to be taken seriously.

For anyone in the business of trying to be serious about this, then, the action is on where you draw the line in the journey from blastocyst to baby: when does the foetus acquire rights that will, potentially, compete with those of its mother? That’s not something you can handwave with an absolutist slogan like ‘my body my choice’, or ‘life is sacred’. There’s harder work than that to do.

We have to acknowledge that people can disagree about this in good faith and disagree extremely. If an accidental pregnancy stands to profoundly immiserate or even kill a woman – or simply change the course of her life irrevocably against her will – you may be horrified at the idea that the law thinks that’s simply tough luck on her. But if you believe a two-month-old foetus is already a person, it follows quite naturally from that that you’d fight tooth and nail to protect them from what you’ll see as institutional mass-murder. Roe v. Wade said, effectively, that it was none of the state’s business in the first trimester. But that’s a human, i.e. a political, decision in a highly contested area.

What’s primarily at issue here isn’t the issue: it’s where the issue is decided. That’s what in rhetoric gets called translative stasis. And it doesn’t seem to me automatically evil to suppose that this is a question better settled by elected state legislatures than by judicial fiat.

Is that supplying cover for a misogynist attack on the freedoms and safety of some of the poorest women in American society? Many think so, and they may well, in big picture terms, be right. There’s something nasty in the air when oven-ready laws are drafted pre-emptively so the government will effectively own your womb the moment, for whatever reason, you conceive a child. As the dissenting judges in Dobbs put it, this would mean that ‘from the very moment of fertilisation, a woman has no rights to speak of’.

But the constitutional argument should be settled on its merits: the moral and the constitutional points are somewhat orthogonal to each-other. Even if you’re firmly pro-choice (by which I mean supportive of a right to abortion at some point after conception) the Roe v. Wade status quo was, as many feminists acknowledged and last week made clear, a pretty shaky and contingent basis on which to secure that right.

Where I fall firmly back in with my tribe is when we consider the practical effects rather than the points of principle. You end up in a very weird and dangerous world if you concentrate on the principle behind a law you put in place to the exclusion of its real-world implications. As pro-choice advocates are rightly fond of pointing out, criminalising abortion doesn’t stop it happening: it just makes it more dangerous. What does it mean, culturally and practically, to regard first-trimester abortion as murder in one state when, potentially, it’s a medical procedure just across the state line?

What will those disparities do to compound the existing divides in the country? It will always be far easier for the wealthy to travel, for the wealthy to preserve their privacy against judicial surveillance, for the wealthy to get away with it. The burden of danger, surveillance and punishment will fall disproportionately – as abortion already does – on the poor. And if you are so determined to show your love for children that you don’t much mind if the law you make actually works to protect them, that’s a textbook example of the ‘virtue-signalling’ conservatives are in other circumstances quick to denounce.

A gospel of love that ensures unwanted children are born into loveless and desperate situations, will in some cases retraumatise rape victims, and will in many, many cases lead to the painful deaths of already living women and children in botched surgery is a gospel that might be worth, I’d suggest, a second look.

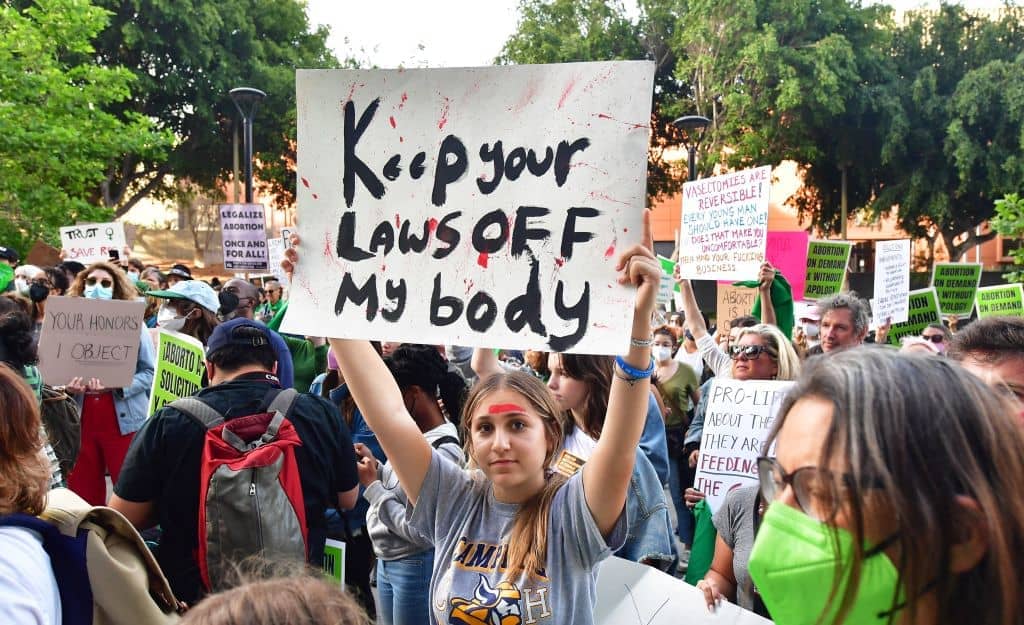

The people who need to be taking that second look are American citizens, at the ballot box and in the streets; exactly as the Supreme Court has now asked them to. Not as a culture-war ‘wedge issue’, but as a matter of deep importance. I wish them luck with it.

Comments