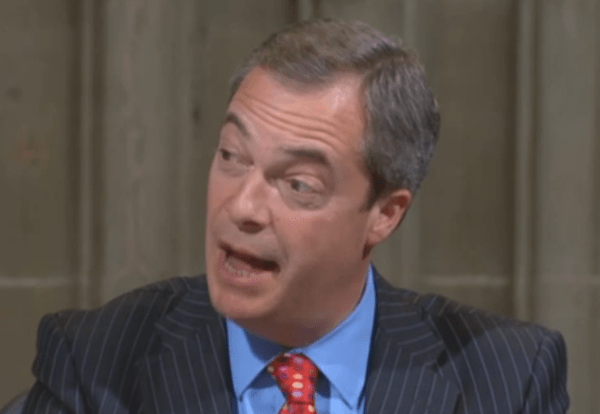

Nigel Farage was on Question Time again last night. This was hardly unusual, but what was interesting was that the UKIP leader U-turned on one of his flagship policies.

When he spoke at a press lunch on Tuesday, Farage accepted that UKIP’s flat tax policy was ‘incomplete’, but that UKIP’s aspiration was to have taxes as low as possible. Last night, asked whether he still wanted a flat tax, he said:

‘It was in 2010, but it isn’t now, and don’t tell me about manifestos: you haven’t even got one!’

Simon Hughes pressed him on what his tax policy was, to which he replied:

‘We will have no tax on the minimum wage and a mass simplification of the tax policy, with a lower rate. We will abolish National Insurance, roll it into tax because all it is is tax anyway.’

He added that higher earners would pay ’40 per cent or something like that’, adding:

‘Every party changes their policies between general elections… Just because we stood under a different leader in a different general election with a policy of 31 per cent, doesn’t mean that’ll be our policy next time round: it won’t.’

Farage’s selling point for lunches, hustings and the many, many broadcast appearances he is invited to make is that he brings colour to a world of grey suits. He’s funny, he’s eloquent, and he likes to emphasise his branding as someone who says what other politicians daren’t say, whether it be about immigration or lap-dancing clubs. But as I explained earlier this week, this comes at the expense of policies, because he doesn’t really need many of those to get the sketchwriters and reporters looking for a colour piece along to his events.

Of course, any simplification of the tax system would be welcome: this morning’s Today programme debate with Margaret Hodge about tax accountants seeking more loopholes to exploit underlined that.

The panel also, inevitably, discussed the effects of the end of transitional controls on Bulgarian and Romanian migrants. Farage came under fire from his fellow guest Natalie Bennett, leader of the Green Party, for his rhetoric on immigration. When he had his chance to have a say, Farage made a characteristically robust and eloquent defence of his position, followed by Luciana Berger, who deployed what appears to be the new Labour line to take on immigration, which is to say it’s OK to be worried about it, but not much beyond that. She said:

‘We have a proud heritage of immigration in this country, but it’s not wrong to address people’s very serious concerns about immigration: I hear it all the time. We need to look at the facts and the challenge is that we don’t actually have the facts from this government. We don’t know how many people might come here because we don’t have the facts from this government. We don’t know how many people might come here because we don’t have figures from government and that obviously makes this conversation incredibly challenging.’

Berger’s answer points to one of UKIP’s key campaigning strategies: it trades on uncertainty. Two different select committees took evidence on migration statistics this week: the Home Affairs Select Committee heard from the Bulgarian and Romanian ambassadors, who predicted between 8,000 and 10,000 Bulgarians and between 15,000 and 25,000 Romanians would come to Britain in 2014.

The following day, the Public Administration Select Committee took a rather dispiriting tranche of evidence on just how unreliable these figures are. Committee chair Bernard Jenkin told Dr Scott Blinder, director of the Migration Observatory, Cllr Philippa Roe from Westminster Council and Professor John Salt from the Migration Research Unit that the picture they had painted was ‘bleak’, with all arguing that not only was it very difficult to have faith in statistics on who was arriving, and who was leaving, but it was even more difficult to predict who might arrive. Salt told the MPs on the Committee that ‘I would be extremely surprised if there isn’t a file somewhere which has got some numbers in it’, but even if such a file became public, it would be difficult for voters worried about immigration to know which number to trust, given there are so many circulating. And UKIP can feed on that uncertainty, in the same way as it feeds on uncertainty over greenfield development, or uncertainty over whether David Cameron really will make good his promise on an EU referendum.

But perhaps other political parties will see UKIP’s own uncertainty over policies and feed on that, too. The local and European elections will be bruising because they don’t focus the mind on tax policies, but in 2015, Farage’s opponents will want to use any dithering as a sign he’s better kept as a good lunch guest in Westminster.

Comments