Here’s the thing. This box-set business. Do you get it? I tried. I failed. But everyone else goes stark raving mad about these fictional treasures. Once you’ve sampled a box set (or boxed-set?), you’re hooked.

Here’s the thing. This box-set business. Do you get it? I tried. I failed. But everyone else goes stark raving mad about these fictional treasures. Once you’ve sampled a box set (or boxed-set?), you’re hooked. You won’t be seen again until you’ve visited every corner of the dream kingdom encased within its magical walls. Didn’t happen to me, though. I sat through the first six minutes of The Wire in total bafflement. It seemed to be a style programme about a clique of young entrepreneurs posing on a sofa which, perhaps to facilitate the public’s admiration of its proportions, had been stationed outdoors. In England, the best families throw their homes open to the public. In Baltimore they throw their homes on to the street. Perhaps I was missing something.

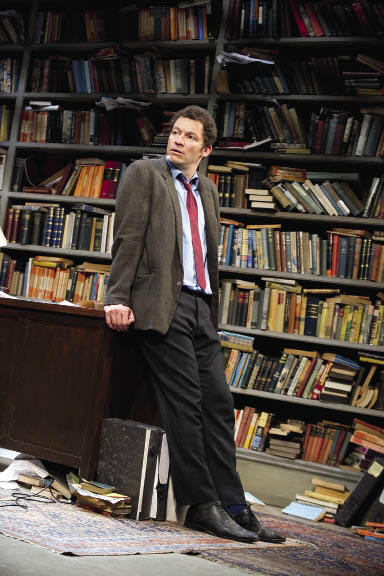

The man who called that box set home, Dominic West, wants to make a career here as a light theatre actor. In his new play, Butley, he plays an angry, witty, bisexual English lecturer who loses everything he cares for in the space of a single day. West is excellent. His handsome looks are rough-at-the-edges and approachable. He has a warm, expressive voice and a playful spirit, a sort of dashing silliness, that suits this frivolous material perfectly.

The script, Simon Gray’s first big hit, is plotted artlessly, mechanically. One by one Butley’s friends desert him, and his enemies, one by one, are rewarded with the success that eludes him. At least two of the roles are microscopic. Poor Amanda Drew, playing Butley’s wife, has to get all glammed up for a West End hit and is forced off-stage and back to her dressing room after about ten lines. The climax is a showdown between a gay northern publisher and Butley over a disputed boyfriend. Butley’s mockery of the Yorkshireman’s self-regarding swagger, served up in a triple-thick accent, is deliciously funny. And it’s a particular treat for modern audiences because new-fangled taboos restrain us from sticking it to the sticks with too much enthusiasm.

But even this highlight — which may baffle Americans by the way — is bedevilled by an unforeseen snag. Paul McGann, the publisher, can’t do a Yorkshire accent. He comes close-ish, at times, to places that aren’t too far from his target county. A hint of Newcastle here, an echo of Nottingham there, but it’s a very unconvincing tour of the A1. West’s impersonation, meanwhile, of the verbal oddities McGann is failing to replicate is perfect. So the model West is mimicking is absent. Very strange. May I offer Mr McGann some advice on imitating Yorkshiremen. Imagine you’re Sean Bean awaking from a coma and reading a list of pies.

Dominic Cooke, boss of the Royal Court, has been flipping through the back-catalogue in search of neglected classics. Or, if you prefer, he’s gone back to the kitchen sink to see if it’s still blocked. Arnold Wesker’s play, Chicken Soup with Barley, which opened at the Court in 1958, plunges its audience into the East End of London during the turbulent 1930s. We meet a warm-hearted bickering Jewish family as they prepare to sock it to the fascists at the Cable Street riots. Fast-forward two decades and their idealism has died. Stalin executed the committee of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Defence League. Soviet tanks crushed the ’56 rising in Hungary. And Uncle Monty opened a grocers in Salford.

Absolutely nothing is wrong with Dominic Cooke’s pacy production. He faithfully reproduces Wesker’s faithful account of a faith that went awry. It’s unfortunate that this dramatic milieu, working-class Jews struggling to temper idealism with reality, has been explored with far greater subtlety and dramatic power by Arthur Miller. To revisit such a well-known resort in the company of a lesser tour guide creates a sense of absence and loss. It’s no criticism of this show to point that out. The fact is that Miller’s great mid-century Jewish tragedies entirely eclipse this slight and feeble replica.

The play is ill-crafted and creaky with symbolism. A curmudgeonly old commie suffers a series of strokes which are supposed to offer a commentary on Marxism’s waning influence. The play’s take-home message is that those who understand the cause least remain most loyal to it. Worth writing on a postcard, perhaps. Supporters of the kitchen sink would argue that Wesker’s artlessness was proof of his integrity, a badge of honour, a rebuke to the ‘well-made play’ which he and his chums were desperate to depose. In that sense this production is revealing. In hindsight the kitchen sink revolt looks like an entirely imaginary effort. It was an act of spiritual will not of creative art, a conjuring routine dreamed up by an ardent and essentially comfortable bourgeoisie which knew it wanted to experience a revolution and also knew it didn’t want to break anything.

Comments