Man plans, God laughs. Fide, the international federation, organised an Online Olympiad, with 163 teams taking part. We got a global internet outage during the final. The disruption hit the Indian players at a critical stage, in the second of two matches against Russia. (The first was tied 3-3).

India were soon to be trailing 2.5-1.5, but had realistic hopes to even the score on the two remaining boards. But when those two players lost their connection to the website where the games were played, their time elapsed and they lost. The Indians lodged an appeal, but the appeals committee couldn’t reach a unanimous verdict. It fell to Fide president Arkady Dvorkovich to settle the matter. Dvorkovich is Russian, so an impartial ruling was impossible. He awarded gold medals to both India and Russia. An awkward compromise, but sound politics.

If the conclusion was unsatisfying, it wasn’t for lack of planning. The Online Olympiad was a substantial organisational effort. It might sound straightforward: 99 per cent of the time, internet chess works flawlessly. But the possibility of cheating, made all too easy by modern chess engines, has prevented online games from being treated seriously. Cheating over-the-board calls for furtive bathroom breaks, and a risk of being caught red-handed. To cheat online, all you need is an engine running in a separate window.

The elite online events of recent months had far fewer players, who one assumes had too much to lose to consider cheating. But the Online Olympiad cast a wider net, and much of the planning anticipated the possibility of foul play. The players joined a Zoom call and shared their screens while playing, scrutinised by arbiters. Extra windows were forbidden, and so was leaving the webcam’s view during games. There were statistical checks for superhuman play. Overall, the chief arbiter — England’s Alex Holowczak — struck a healthy balance. The anti-cheating rules were extensive but workable.

Disconnections were planned for too. Broadly, players were considered responsible for their own internet connections, come what may. When a power cut cost them crucial points, the Indian team were held to a draw by Mongolia. In the quarter-final, India benefited when an Armenian player lost his connection to the playing server for unclear reasons. It seemed to me harsh but justifiable when Armenia’s appeal was rejected. But the players’ disconnections during the India-Russia final could be seen more as an act of God — apparently stemming from a well-publicised outage at an ISP in the US. It is only by chance that a compromise was tenable at all — the match genuinely hung in the balance, and there were no later stages of the competition.

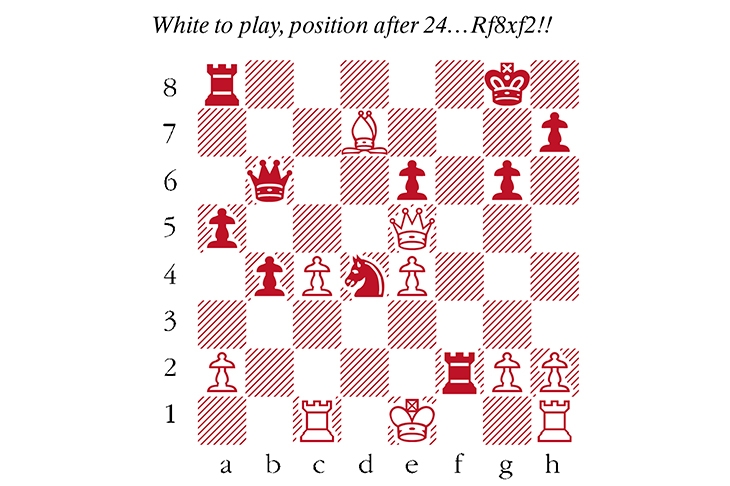

Here’s a wild game from the first match of the final. In the diagram, ‘Nepo’ has just uncorked 24…Rf8xf2!!, capturing a pawn.

Santosh Gujrathi Vidit–Ian Nepomniachtchi

Fide Online Olympiad Final, August 2020

25 Kxf2 25 c5 Qa6! 26 Bxe6+! (Not 26 Kxf2 Qe2+ 27 Kg3 Nf5+!) Nxe6 27 Kxf2 Rf8+ followed by Ne6-f4 is very dangerous. 25…Rf8+ 26 Ke3 26 Ke1 Nf3+! 27 gxf3 Qe3+ 28 Kd1 Qd3+ draws, or 26 Kg3 Ne2+ 27 Kh4 Qd8+ 28 Qg5 Qxd7 is utterly unclear. 26…Nf5+ 27 Kd3 Qe3+ 28 Kc2 Nd4+ 29 Kb1 Qd3+ 30 Ka1 Rf2! Just in time. Now Rxa2+ will force a perpetual check, so White has nothing better than to force a draw himself. 31 Bxe6+ Kf8 32 Qd6+ Kg7 33 Qe7+ Kh8 34 Qd8+ Kg7 35 Qe7+ Kh8 36 Qd8+ Kg7 37 Qe7+ Draw agreeda

Comments